During World War II, in Japan and Germany, there was a pact of silence when ordinary citizens ignored the thousands of casualties and the bombing of civilian targets. Today, during the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, the same thing is happening: people turn a blind eye to the systematic murders and try not to talk about the genocide. Zaborona executive editor Daniel Lekhovitser ponders why historical cataclysms cease to be the central core of human consciousness and are instead pushed into the territory of oblivion and ignorance.

“Brick hills, under them – buried, above them – stars; the last ones moving there are rats. In the evening I go to listen to ‘Iphigenia’ – these are the lines from the diary of the German writer Max Frisch, written in Berlin one of the days following the bombing of German cities by the Allies. A rare (but, as it turns out a little later, quite ordinary) combination of the reality of ruins with secular life, the neighborhood of corpses burnt after shelling and subcutaneous fat frozen on the cobblestones with people waiting for the start of the opera in the lobby.

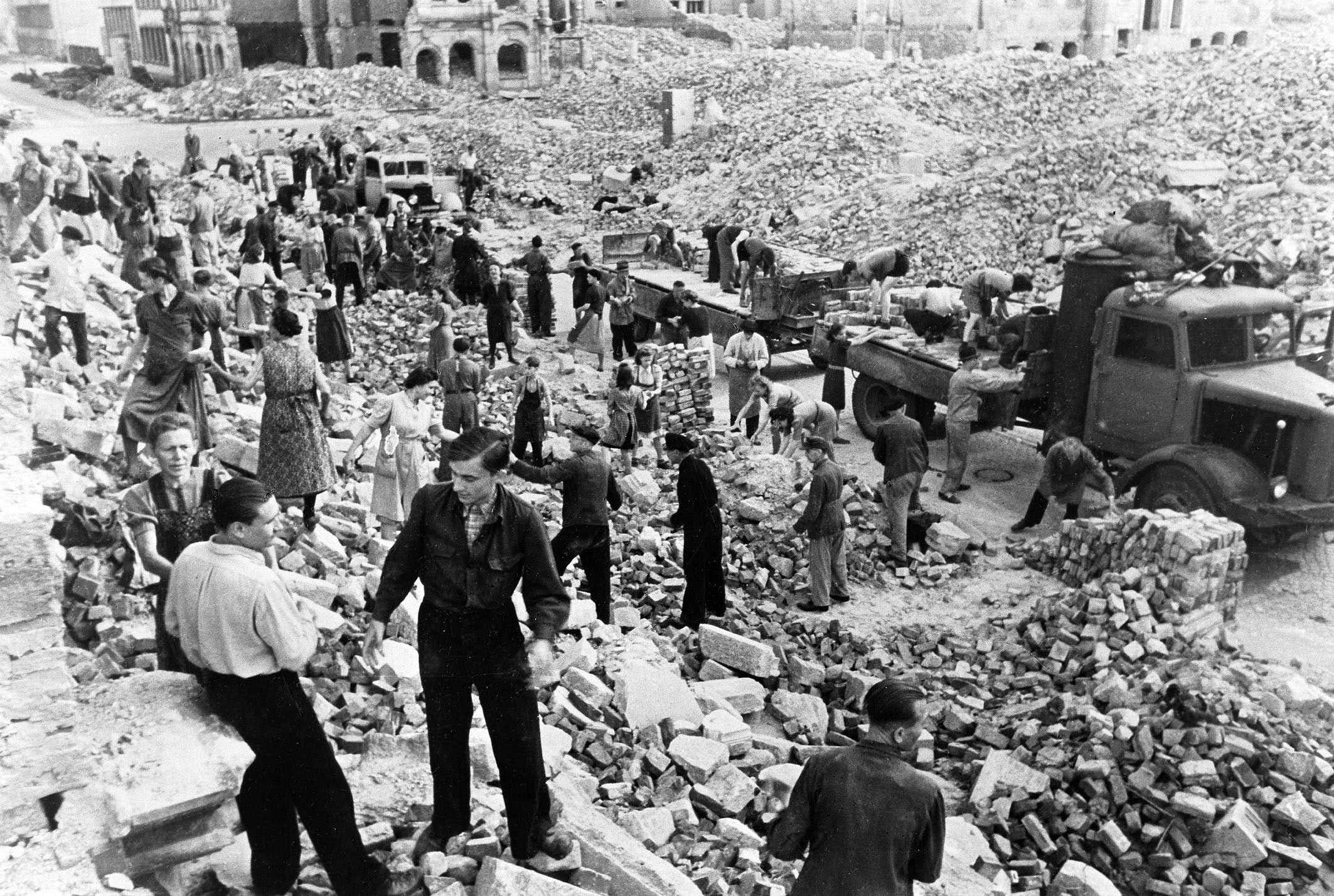

According to some estimates, about 600,000 Germans died during Allies air raids in Germany, and 31.4 and 42.8 cubic meters of debris fell on one inhabitant of Cologne and Dresden, respectively. This is what the bombing of civilian infrastructure looked like during World War II. Perhaps more striking is the discrepancy between the scale of the tragedy and its depiction – or rather, the absence of such a depiction. The Germans, with their love of keeping diaries, left surprisingly little material about, perhaps, the most terrible events of the war for them. The whole country seems to have resorted to collective hypnosis.

-

An American soldier asks the residents of Cologne to go to the shelter, March 7, 1945. Photo: Fox Photos/Stringer via Getty Images -

A man sits next to an American tank in the ruins of Cologne, March 21, 1945. Photo: Bettmann via Getty Images

Another thing is no less impressive: the few notes about how, the very next day after the bombings, the Germans begin to wash windows, soap the steps of their own houses, or polish their shoes before the coming evening, as if thoughts of the historical cataclysm can be wiped away with circular polishing movements. A foreigner in the Reich, if we believe one road note, was very easy to recognize: in public transport, only foreigners looked out the window. The Germans decided: if you don’t look, the ruins behind the glass can disappear under favorable circumstances.

-

The ruins of Dresden after the massive bombing, 1945. Photo: Richard Peter via Getty Images

Witnesses of tragedies, it seems, should have shouted about them to the whole world, but instead turned into the strictest censors of the history of disasters. Why are the funnels of history hidden behind a new layer of cobblestone pavement, and the charred bones and carcasses of houses dissolve in memory, supplanted by household chores and a routine cup of coffee? In other words, how does a whole nation come to the idea of collective silence and praise of forgetfulness?

Another equally striking example is the victims of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, the hibakusha. In Japan, the hibakusha — a voiceless and economically and socially vulnerable group of survivors — have become something of an internal emigrant. They quickly began to be treated negatively, as if the very presence of hibakusha as witnesses of the disaster was unfair to postwar society. After all, as say, for example, some historians of the Holocaust, the real witness of horror is a dead witness. The dead are easy to honor, unlike the pesky living ones.

-

The consequences of the atomic explosion in Hiroshima, August 1945. Photo: Universal History Archive via Getty Images

The pact of silence between the Germans and the Japanese with the ruins became something like a virtue, because only in this way, by agreeing on rules and taboos, is it possible to save the mind. But is it important that the whitewashing of the memory of the catastrophes by these two nations is dictated by a general sense of collective responsibility (and at the same time unwillingness to admit it) for what German and Japanese militarism did? A canonical ghost story or gothic novel almost always deals with these very feelings: guilt, shame, and unwillingness to acknowledge them.

After all, in the literary tradition, a ghost appears when the circumstances of his death are shrouded in a shameful secret. Guilt is the main machine for the production of phantoms, that is, those whom it is convenient to deny. The ghost will appear as long as it is denied. But the ghosts do not annoy but remain invisible, like hibakusha in the shacks and the catastrophe that the living in bombed-out Cologne, Stuttgart, and Dresden agreed to keep silent about.

Russia today is not experiencing war as such — it is not going through the destruction of civilian infrastructure, a humanitarian crisis, or street fighting. Muscovites visit restaurants on the Patriarch’s ponds – much like it was in Jonathan Littell’s The Benevolent, where the Germans ate lobsters while the world around them was literally on fire. And yet, in some sense, Russia is going through a catastrophe – a catastrophe of selective blindness and memory deficit. More than rules and taboos, society is bound by the pact of silence and anesthesia with routine, as if your state does not produce systemic genocide.

-

A boy with friends near his mother’s grave in Bucha, April 5, 2022. Photo: Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

After all, news and videos of shot Ukrainians are just virtuality in a Telegram channel, ephemeral and woven from thin air, like a ghost. The main thing is not to watch the news too often, just as the Germans did not look from the windows of their trains. It is advisable not to meet each other’s eyes. ‘Iphigenia’ may be performed in the evening.