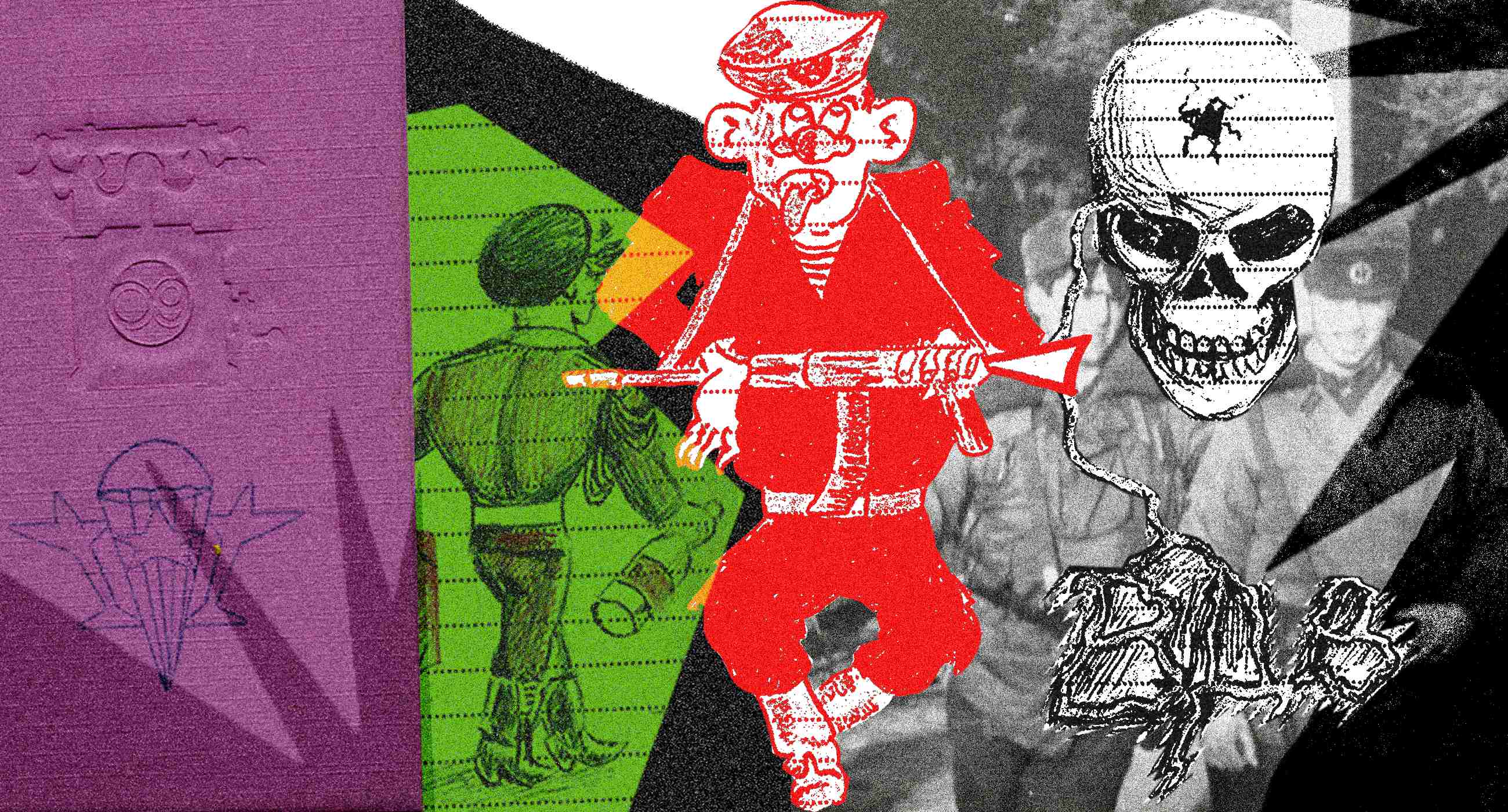

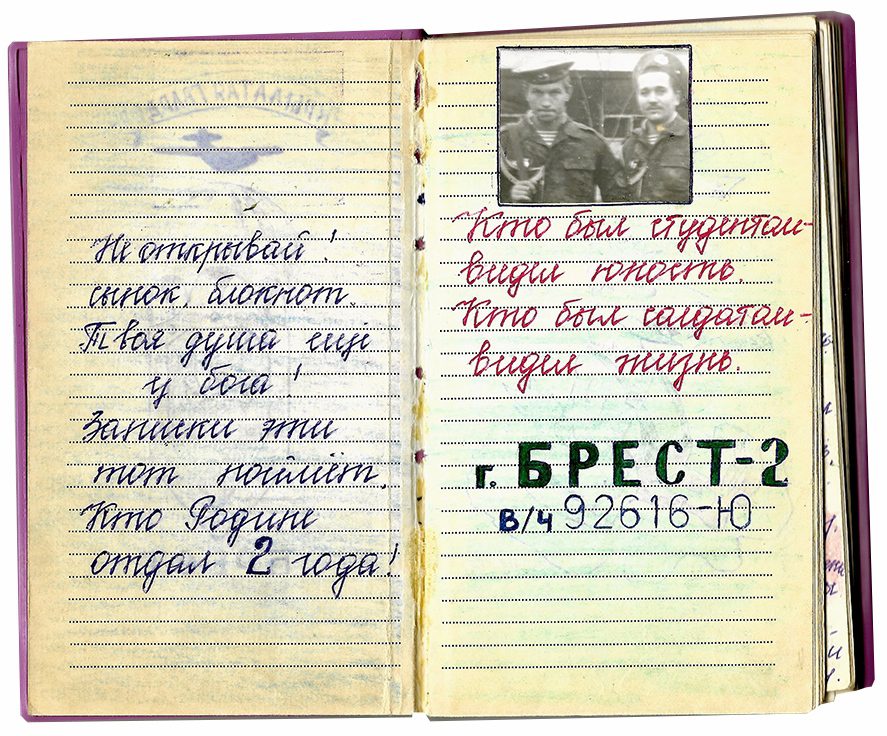

Soviet army soldiers had a tradition: after completing their military service, they created a so-called Demob photo album. Debaltseve native and Kharkiv resident Oleksandr Magula served in the Soviet army from 1988 to 1990 and turned his album into a visual diary. His son, Oleksandr, who works as a photojournalist and covers the war in Ukraine, shared with Zaborona his father’s diary and archival photos from his service. Magula Sr. explained how he worked on the diary, why a Russian paratrooper crushed the skull of an African-American NATO soldier, and how the airborne troops were combined with the Nazareth band.

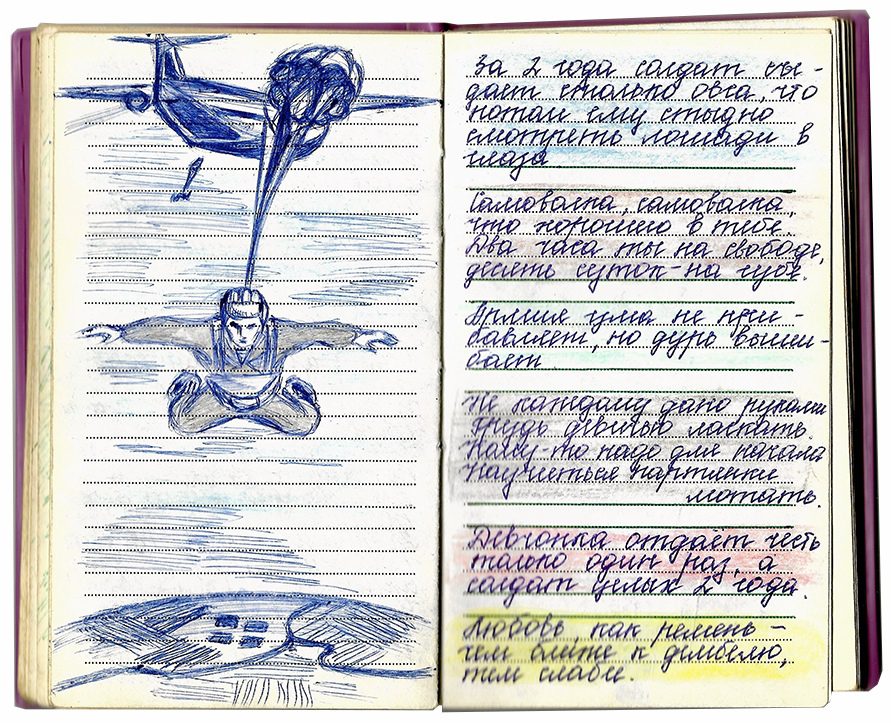

“I was actively involved in physical education, weightlifting, and bodybuilding in my youth. And, like most children from working families, my dream was to join the airborne troops. Then the so-called buyers — officers from different parts of the Union — came to the military enlistment office in Donetsk to choose the number of soldiers they needed. That’s how I was chosen to serve in Brest. This military unit is now called the 37th separate airborne assault brigade — it is one of the best-prepared brigades in the Belarusian army (and now it is on the border with Ukraine).”

“January 1990. Due to the ethnic conflict between Azerbaijanis and Armenians, the USSR leadership declared martial law in several regions of Armenia and Azerbaijan and sent 11 thousand of troops there. The military unit 926616-Ю in Brest, where I served at that time, was put on alert. We were given 4 cartridges of ammunition and 2 grenades. From the military airfield in Baranovychi, about 2 thousand paratroopers from my unit took off in the direction of Baku on military transport planes — the operation deliberately did not include military from Azerbaijan or Armenia. The unit commander announced the peacekeeping and restoration of order operation and forbade to inform parents about it”.

Shooting from a D-30 howitzer during military exercises. Belarus, 1988-90s. Photo courtesy of Oleksandr Magula

Oleksandr Magula (below) with his fellow soldiers during military training. Belarus, 1988-90s. Photo courtesy of Oleksandr Magula

“Our military unit did not participate in active hostilities. There were some shootings, there were chaotic shots in our direction, and we shot back. No more than that. The most active hostilities were two days before our arrival. It seems that the Pskov Airborne Division, which had been transferred there earlier, took part in them. At the moments of the threat of mass riots, we were taken to the city center, where we sat in the building of the House of Culture, waiting for the command. However, mass actions were peaceful and our unit returned to the place of deployment”.

“We walked two by two, with machine guns on our shoulders, with the safety off. Baku residents looked at us as invaders. One of the few entertainments I had was fishing with my colleagues. With a net made of medical bandages, contemplating the horizon of the Caspian Sea with oil towers, we caught shrimps smacked of oil.”

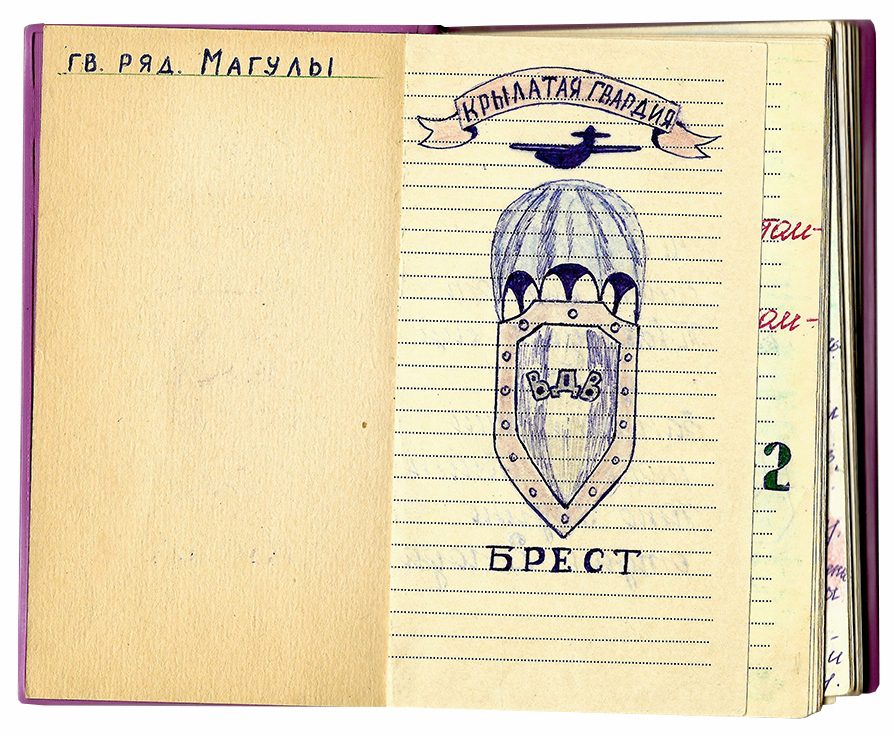

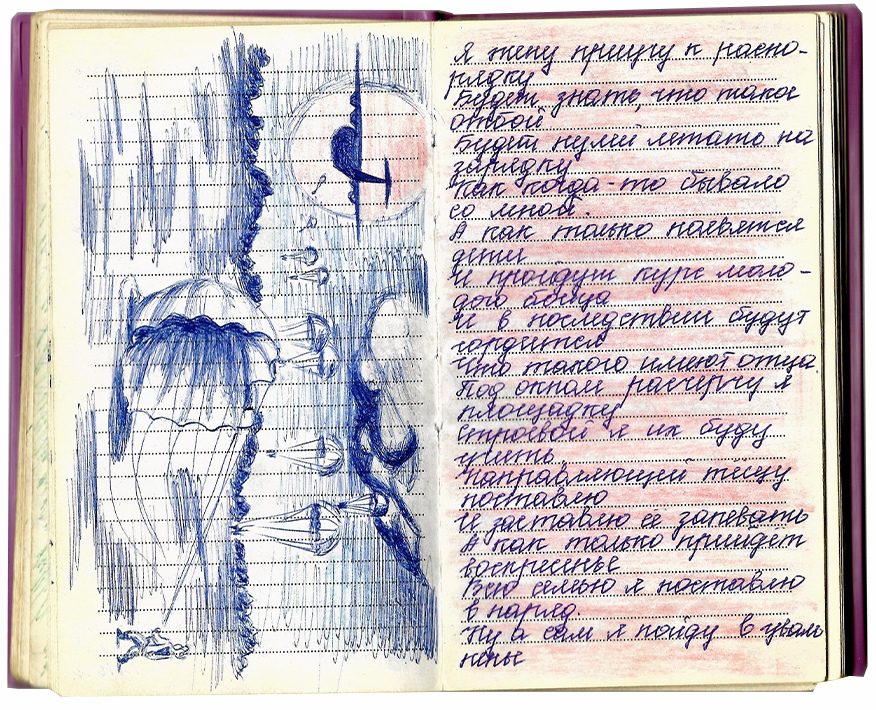

“This is a phone book, which I turned into a diary. Almost everyone had such a notebook — even those who did make a demob album. Sometimes I take it, re-read it and it’s kind of funny to me. I wanted to make a drawing of a parachute dome with a military plane flying over it and a shield with the inscription Airborne Troops as a tattoo on my arm. However, I never managed to do it — the tattoo artist quit.”

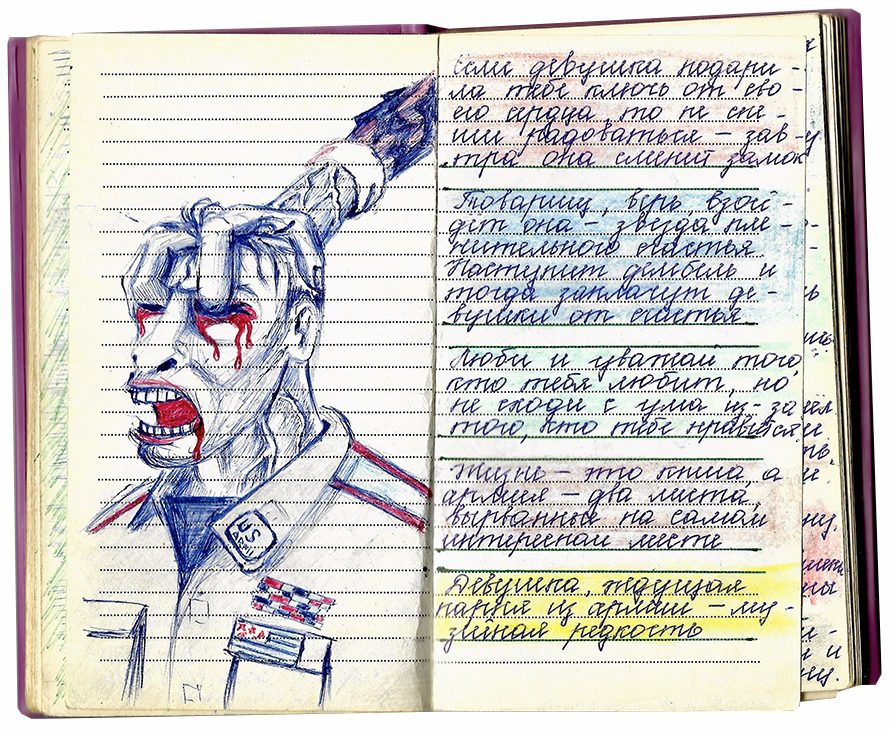

“The military propaganda of the time [during the Cold War] convinced us, very young, that we were rangers who could beat everyone. Like the paratrooper in my drawing can crush an African American.”

“When I was young, I was into rock music and the band Nazareth, and something similar was on the cover of their vinyl. I think that [the monster holding the abbreviation Airborne Troops] is from there.”

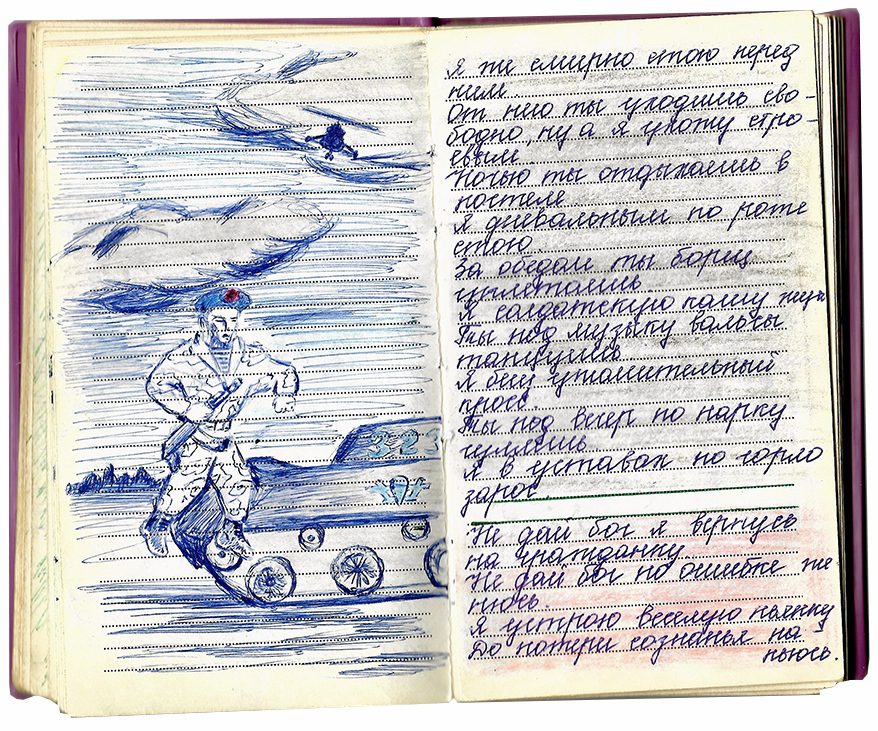

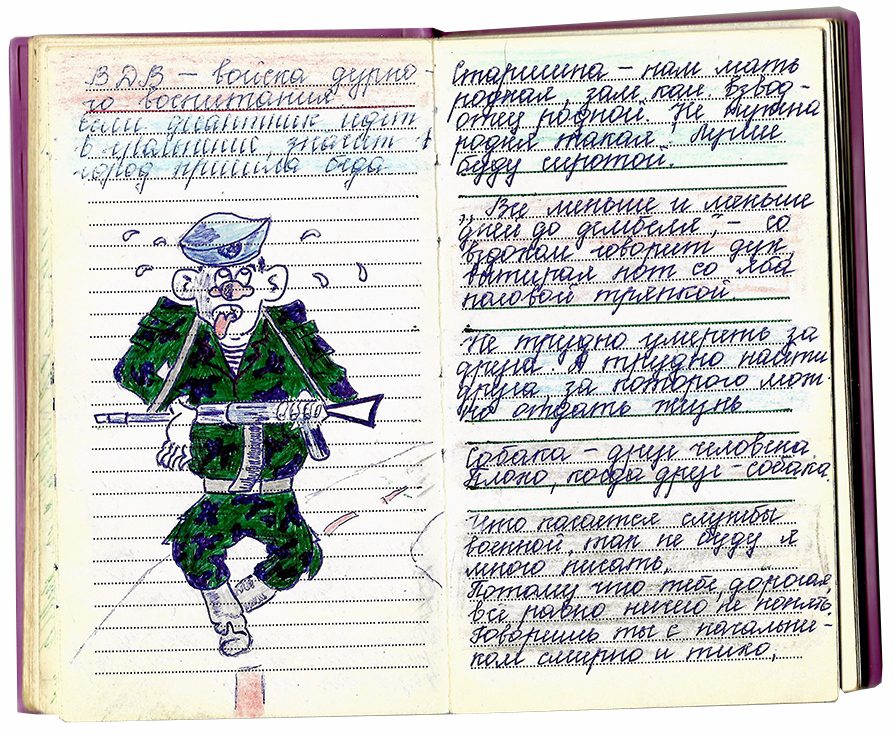

The expression “Airborne troops are troops of bad education. If a paratrooper goes on leave, it means that trouble has come to the city” can be explained by the traditional behavior of Soviet paratroopers after demobilization, such as drunkenly walking around the city in vests or swimming in fountains. For example, such behavior of the military is still observed in Russia.

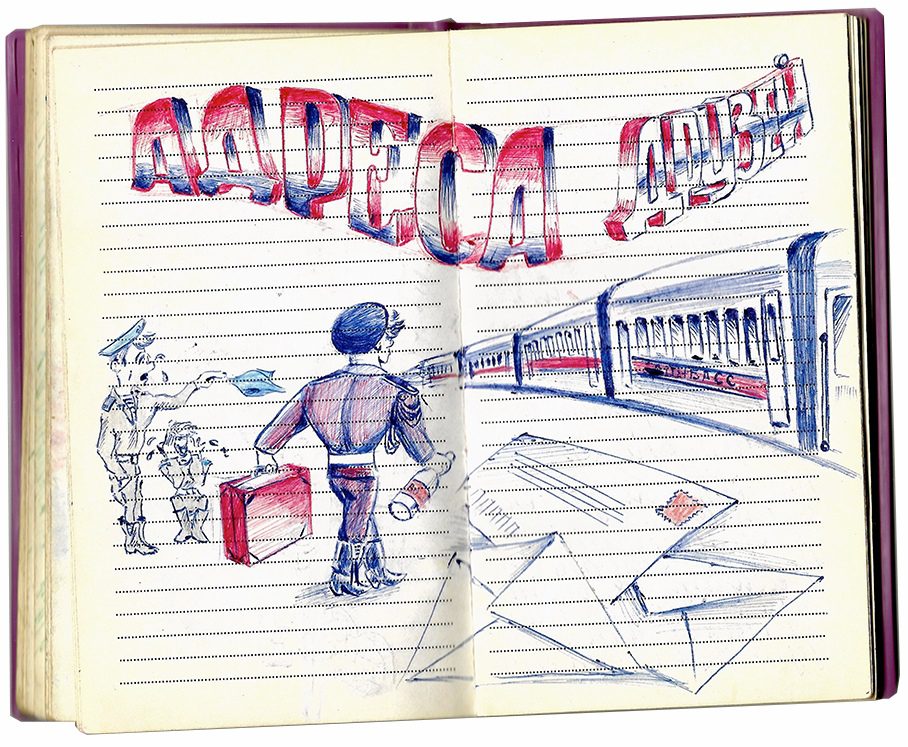

“On the last pages of the notebook, the military usually wrote down the home addresses of their colleagues. I always kept in touch with my best friend from the army, Yuriy Karasev from Volgograd, we often called each other. After the annexation of Crimea in 2014, due to the difference of views, we had a conflict, and our long-standing friendship of comrades-in-arms ended. Yuriy served in the Russian army all his life and now he should be on a military pension. I do not exclude that he is now fighting against Ukraine somewhere”.