“Smart Militarization”: Will the military training for politicians discriminate against women’s political rights in Ukraine?

Recently, the Minister of Defense of Ukraine announced that in the future civil service employees will probably have to undergo military training. Everyone who does not meet these standards will not be able to take the position. But isn’t this requirement an indirect discrimination that would limit people with disabilities and women? Zaborona asked Olena Strelnyk, a doctor of sociological sciences and gender researcher, to predict how this possible decision will affect the military and state gender policy and whether Ukraine will not face a “rollback” when politics will once again become a space for men only.

In August of this year, the Minister of Defense of Ukraine, Oleksiy Reznikov, published the article “Ministry of Comprehensive Defense” on the Ukrayinska Pravda blog. In it, among other things, he noted that “the presence of military training should become one of the mandatory requirements for working in the public service, as well as for running for elected positions in local self-government bodies and parliament. And all citizens, without exception, must become part of the country’s comprehensive defense.”

First of all, I want to emphasize that this is the opinion of the Minister of Defense, and not a legal act. However, it is already important to follow the formation of certain trends and discourses and respond to them, because sooner or later the state policy will be adapted to long-term security challenges. And the gender issue will not be the last in this process, because, most likely, military training to one degree or another will concern both men and women.

However, I am concerned about the risks of such a policy for women, particularly in terms of military training requirements for public service and for running for elected office. Ukraine has achieved a significant increase in the representation of women in government bodies, in particular in elected ones. In recent years, the share of women members in the parliament has increased by 9%, in regional councils — by 12%, and in city councils — by 4%. Not least, this happened due to the gender-based quota mechanism in party lists.

Is there a risk of “rollback”? Political parties have previously complained about difficulties in recruiting women to their ranks. If there is a requirement for military training or service to run for office, it will be much more difficult for parties to meet these quotas. After all, even if the article quota is formally respected, the women who meet these requirements and will be included in the party lists will represent only a certain segment of society. Instead, civilian women or women without such training will be eliminated from political activity, just like the corresponding group of men. The same applies to civil servants: there is a risk of a decrease in the share of women in the civil service.

In order for the rule proposed by Mr. Reznikov not to be discriminatory, it is first necessary to make sure that all citizens of Ukraine really have equal rights and equal opportunities to undergo military training. If this norm were to be introduced now, without a transition period, it would be a manifestation of indirect discrimination against women, because currently, much more men in Ukraine have experience in military training and service in the Armed Forces.

-

Illustration: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

The military sphere in Ukraine has traditionally been masculinized. Only since 2015, with the start of the war in Donbas, did the share of women in the professional army begin to grow — previously forbidden military positions were opened for them. These changes were mainly the result of the Invisible Battalion project, which included a study of the position of women in the Armed Forces of Ukraine and an advocacy campaign to expand the rights and opportunities of military women. As a result, the Ministry of Defense significantly expanded the list of combat positions for women serving under a contract, and the topic of the position of women in the army began to be widely discussed in society. Currently, 38,000 women work in the Armed Forces, of which 5,000 are fighting on the front lines. The share of women in the Armed Forces is 16%, which is a higher indicator compared to the share of women in the armies of NATO countries.

Women’s access not only to military service but also to secondary special and higher military education was difficult until recently. And it is not only a matter of gender stereotypes but also of direct legal restrictions. Only since September 2019, access to study at military lyceums was opened to girls. For example, only in 2021, did girls graduate from the Kyiv Military Lyceum of Ivan Bohun, for the first time in its thirty-year history. In the same year, 2019, the restriction on the admission of females to study at higher military educational institutions was canceled — as a result, 16% of girls entered military universities, including the most masculinized specialties — for example, the Institute of Tank Forces.

Some of the women in civilian professions have undergone military training and are conscripted — these are women who have, for example, a medical education. However, as of now, in general, the share of women who have undergone military training is disproportionate to the share of men. The same applies, for example, to people with disabilities, the vast majority of whom are also not covered by military training or do not have military experience.

Taking into account these conditions, the introduction of the requirement for military training as a condition for acceptance into public service or running for elected positions and government bodies will inevitably cause a sharp decrease in the share of women in decision-making spheres, which will be a rollback of significant achievements in the field of gender equality. In the conditions of Ukraine acquiring the status of a candidate for EU accession, this will not only be a loss of reputation, because the status of a candidate imposes certain obligations on the country, in particular in matters of human rights, non-discrimination, and gender equality.

Women and military training: What’s next?

Short-term perspective. There are still more questions than answers here: how will the state provide equal conditions and opportunities for military training and what kind of training will actually be considered military? Is it about a military department at the university, will it be about some informal forms of such training, for example, taking courses or training in tactical medicine, will military service experience, etc. be taken into account? There will probably be a transition period that will allow all categories of citizens to undergo training. It is an open question whether everyone will actually be able to use this right. For example, if it is necessary to go to a military training ground for several weeks or months to undergo such training, it is unlikely to be convenient for mothers of young children or single mothers.

From October 1, the Ministry of Defense should begin military registration of women in certain specialties. During the summer, the most annoying thing was the lack of normal communication on this issue: we heard different, often contradictory interpretations of this process from different sources. Will it be mandatory or voluntary? Will the restrictions be the same for conscripted women and men? How will this process be organized — in particular, what will the medical examination look like?

We will have to wait for clear norms and clarifications: so far we see comments by Hanna Malyar (that registration will be voluntary) and lawyers with references to current legislation, which contradict each other. Finally, on September 7, it was announced that the implementation of this process was postponed for one year. In short, militarization should really be “reasonable” — this is the wording Reznikov used in his blog.

Long-term perspective. We are already seeing active discussions about the gender aspects of the state’s military policy. They revolve with varying degrees of vehemence around one fact: by law, military service is an obligation for civilian men and a right for women. Someone believes that this is normal, because men “by nature” should be defenders, and women should support them in the rear; someone reproaches feminists for not fighting against discriminatory norms regarding the ban on travel abroad for men; some call for the introduction of the “Israeli model” with a conscription army for men and women, etc.

First of all, the issue of women’s mobilization is a very sensitive topic for Ukrainian society, and there are no simple solutions here. It’s not that I consider women unfit for service (not all men can serve either, and in the army, there are many different feasible jobs for everyone) or that they should be “protected” for demographic growth (should women of infertile age or those who no longer plan to have children be “protected” in the same way?). It’s just that the army is a part of society — therefore, we need to see the picture comprehensively.

Traditionally, the attitude of citizens to compulsory military service upon conscription in Ukraine was determined by the article. Usually, the system is insensitive to individual situations: it is easier to draw the line of demarcation by one sign (traditionally, it is gender) or a minimum number of signs that are easy to formalize (presence of three minor children, disability, something that can be documented). However, it is likely that the security and conscription system will eventually be reformed and become more sensitive both to the individual characteristics of women and men and to systemic issues.

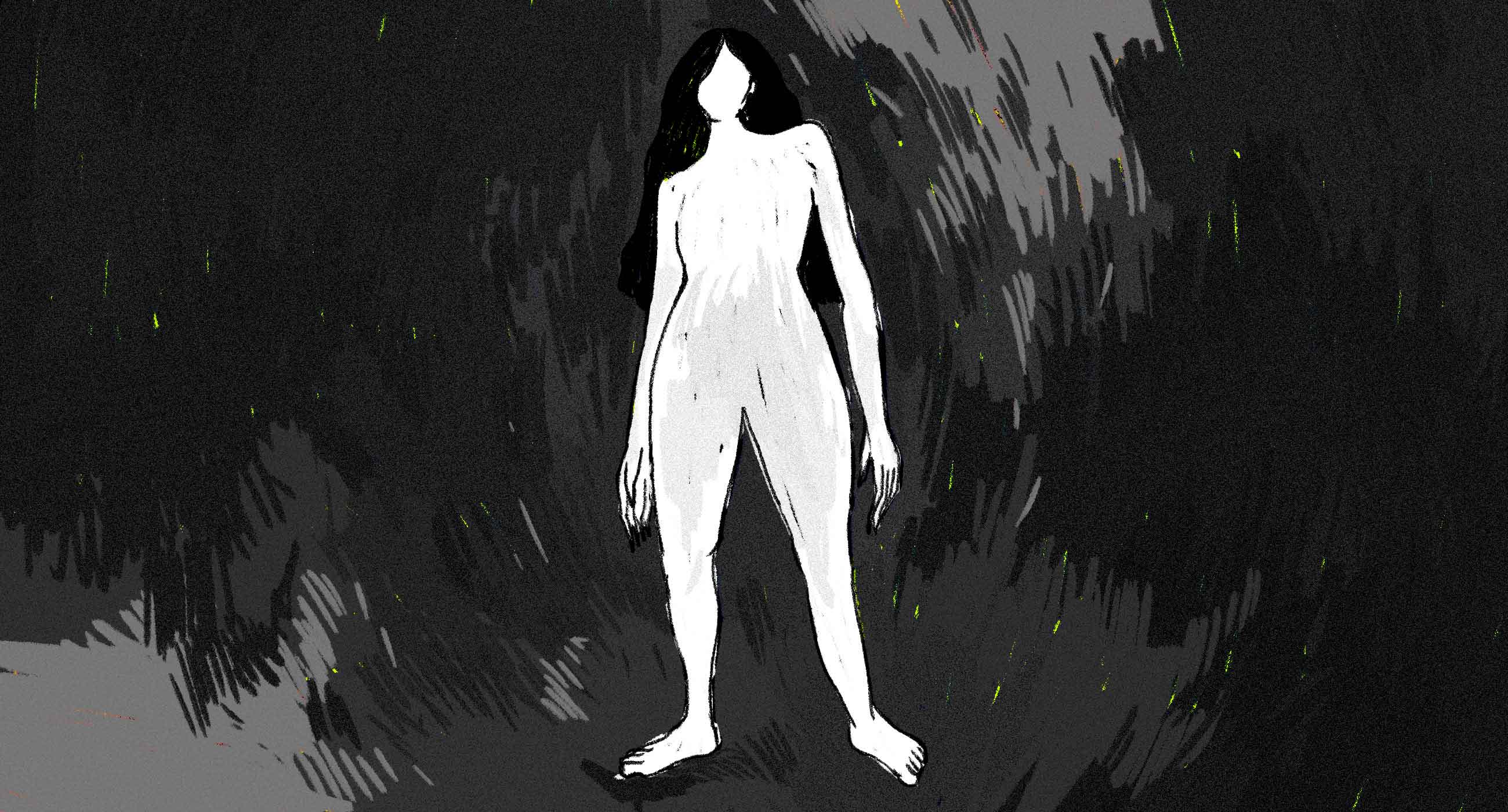

-

Illustration: Maria Petrova / Zaborona

One cannot talk about the reform of the army in terms of compulsory conscription or mobilization for all men and women without talking about other components of the gender order, that is, the distribution of roles in other spheres of life. Even if boys and girls will undergo military training on an equal footing after reaching the age of 18, as in Israel, how will their further life trajectories and opportunities to mobilize them be built in the conditions of the traditional gender order? At the very least, let’s ask the question: who will take care of the children if both parents serve? Someone in the family has to take care of them. Therefore, both parents cannot be drafted into the army. Under the conditions of the traditional distribution of gender roles, when it is women who are actually assigned the responsibility for children, the “choice” to serve or not to serve will be given — mostly men will serve.

Some officials in Ukraine are also suggesting restrictions on women liable for military service, as well as men, in particular, a ban on traveling abroad. Let’s simulate the situation. Both parents are conscripted or a single mother / single father is conscripted. Who and how will take the children abroad in case of aggravation of the situation? Ideally, if the couple has children, the family should decide who will be mobilized and who will take care of the children or use the right to travel abroad with the children. However, under the conditions of the current gender order, mostly women will continue to take care of children (this is roughly like parental leave, which is available to everyone by law, but in fact is used almost exclusively by women).

A transition to a fully professional army could solve many of these difficult questions, but in a full-scale war, a quick transition to a contract army open to men and women is not possible.

Israel’s experience shows that it is possible to build a sex- and gender-sensitive conscription army, but it requires incredible financial, time, and human resources. Israel has been building such a system for decades, and this required radical changes in the system of military policy at all levels: from the sphere of decision-making to the corresponding service infrastructure adapted to the needs of women. Women have changed the face of the Ukrainian army and are contributing to victory, including on the front line. However, at a systemic level, it looks like we’re just taking the first steps on this long road of change — just recently the Ministry of Defense announced the sewing of female uniforms for the military, who now fight in men’s (and this is really inconvenient, not to mention military ammunition unsuitable for women).

In short, militarization should really be “smart”: with sensitivity to the systemic aspects of the position of women in Ukraine, with sensitivity to their needs, and with recognition of their contribution to victory in all spheres of life — both military and civilian.