“I Didn’t Think I’d Ever Shoot an Armed Conflict until the War Started On My Country’s Border.” Zaborona Talked To Polish Photojournalists Who Have Been Working in Ukraine Almost Constantly for Two Years Now

The full-scale war in Ukraine is being covered by journalists from all over the world — many of them came from Poland and have been living and working in both countries for a year and a half. For some, this war is not their first experience of covering an armed conflict, but it is the first time that the threat has come close to their homeland. Zaborona spoke to six Polish photographers who have been documenting Russian crimes in Ukraine since the first days of the war: how this experience differs from anything they have done before, what remains behind the scenes, and how Russia’s attack is being interpreted in foreign media.

The material contains photos that may shock.

Jęndrzej Nowicki

A documentary photographer who focuses his work on events in Eastern Europe. He has also worked in the Middle East and Africa. In his photographic practice, Nowicki is fascinated by humanity’s striving for freedom, whether on an individual level or within entire societies or nations. He has been awarded the Luis Valtuena and World Report Awards.

In Ukraine, Novitsky has covered events for Die Zeit, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, Newsweek, and Le Monde.

My life is now divided between Kyiv and Warsaw, and over the past year and a half I have spent more time in Ukraine than in Poland. I came to Ukraine because Eastern Europe was the focus of my work. I used to cover the events of the Belarusian revolution, and later the refugee crisis on the Polish-Belarusian border.

For me, the full-scale invasion was the next chapter in the tragic history of the region where I was born and raised. It was only over time, as I got to know Ukraine and Ukrainians better, that my interest turned into a fascination and a desire to learn more about the country and its culture.

I still have many images of the war in my memory. One of the earliest is the evacuation across the blown-up bridge in Irpin. I remember the coldness of those days, I remember the crowds of people of all ages seeking shelter on the other side of the Kyiv crossing. I remember the echoes of the battle for Kyiv carried through the air and the horror on the faces of many people. I also remember the question that was constantly hanging in the air: how many more days of battle would the capital of Ukraine endure? Today, we already know that the capital has withstood.

The war in Ukraine is a huge amount of suffering. And although I have been dealing with people’s pain and trauma for many years in my work, I still cannot get used to it. But I try to convey at least a little bit of hope in my photos, which comes from my admiration for the way people can see the light even in the darkest of darkness. I hope that this light is also visible in my photos.

People fleeing under fire across a blown-up bridge. Irpin, March 2022. Photo: Jęndrzej Nowicki

The body of a killed woman in the middle of a park. Irpin, March 2022. Photo: Jęndrzej Nowicki

A boy poses for a photo in a de-occupied village. Kharkiv region, May 2022. Photo: Jęndrzej Nowicki

Nighttime outlines of trees against the background of the ground covered with snow and glass shards. Kharkiv, March 2022. Photo: Jęndrzej Nowicki

Maciej Stanik

Polish photojournalist Maciej Stanik has been working in the Polish media since 2009 and specializes in social reporting. Since 2019, he has been covering events in conflict zones: Afghanistan, Syria, Zambia, Venezuela and Nagorno-Karabakh. Finalist and winner of the Polish Photojournalist of the Year 2020, Grand Press Photo 2020, Viva! Photo awards 2020.

In Ukraine, among other things, he documented the evacuation of civilians from Siverodonetsk in 2022 for the Polish TVN.

I knew that I wanted to document Russian crimes, so this is an important element in the process of establishing justice and compensation for victims. I don’t want to sound arrogant, but if my work helps in this, I see it as my duty as a photojournalist.

I first came to Ukraine at the turn of January and February 2022: Bakhmut, Mariupol, Avdiivka — together with the Wirtualna Polska media team, we studied the moods of people living in the now destroyed cities. At the same time, it was important for me to get as close to the front line as possible: I wanted to see the soldiers defending Ukraine’s eastern border and understand how they cope in the face of the threat of invasion.

Unfortunately, like many other photographers and journalists, I had problems with accreditation (photographer Maksym Dondyuk has already told Zaborona about the difficulties with access to filming), so after two weeks I was forced to return home. The press card was eventually issued on February 23, 2022, and on the day the invasion began, I arrived in Lviv and then in the capital.

For a year, my life was torn between filming in Poland and working in Ukraine. First Irpin, Bucha, Hostomel, then Lysychansk, Severodonetsk and Bakhmut. The first months were the most intense, and now I return to Ukraine every few months and mostly work in the East.

I feel the need to document changes in the world, especially in times like war, when ordinary people are especially vulnerable. I believe that through photographic evidence people have a chance to defend themselves, to speak out, to be heard. Against the backdrop of big politics, I have always been primarily interested in civilians, and I devote most of my professional attention to them. The [war victims] are not an innumerable mass, they are millions of individual lives, each one experiencing cruelty in their own way. The scale of their suffering, the irretrievably lost human lives, the destroyed towns and villages is the hardest thing for me about this war.

I still remember the missile attack on the train station in Kramatorsk. I was having a day off, resting in a hotel. Earlier I was working intensively to make photos of the residents of Severodonetsk who were either fleeing or staying there under fire.

When the first information about the shelling came out, I left immediately. At the station, there were bodies lying along the building, mostly women, as the military put them in plastic bags. On the square in front of the station, I saw investigators working near the wreckage of a Russian missile. There was an inscription on its hull: “For (our) children”. These words were so cruel that they seemed rather unreal.

Later I went behind the houses near the station. I saw the bodies of civilians under a white tarpaulin. I could see the orange vest of a railroad worker under it. Later I saw the body of a girl of five or six years old. She seemed to be sleeping. This image will probably stay with me for the rest of my life. A life that had just begun was interrupted in such a brutal, meaningless way.

A Ukrainian soldier helps evacuate a civilian across a destroyed bridge. Irpin, 2022. Photo: Maciej Stanik

The body of 15-year-old Kateryna after exhumation. Russian soldiers shot her in her car while she was fleeing from Hostomel to Borodianka. Borodyanka, April 2022. Photo: Maciej Stanik

A shot-out inscription “PEOPLE” in front of the entrance to the house. Hostomel, April 2022. Photo: Maciej Stanik

Yevhen stands in front of his house, which was hit by an artillery shell. Irpin, March 2022. Photo: Maciej Stanik

Kasia Strek

Polish photojournalist, member of the Panos Pictures photo agency. She has been a guest lecturer at the Academy of Arts in Łódź (Poland), Michigan State University (USA), Speos School of Photography and École Nationale Supérieure Louis Lumière in Paris (France). She has participated in numerous conferences on long-term documentation and journalistic ethics.

Kasia Strek received the IWMF Courage in Journalism Award for her work in Ukraine for The Washington Post. In Ukraine, she works for The Washington Post, Le Monde, and The Guardian.

I never thought I would cover an armed conflict until the war started right on my country’s border. From the first days of the full-scale invasion, I met people who had suffered unimaginable atrocities so close to where I come from. I realized then that the common, sometimes turbulent past of our countries, my understanding of the geopolitical context of the region, and my knowledge of the language would help me tell the stories of this war.

I feel enormous gratitude for living in a free country, but at the same time, enormous injustice, because the peace has turned out to be so fragile. The war showed how little a human life can mean to someone. The scale of human suffering is horrific: I don’t know anyone in Ukraine who hasn’t lost a loved one, a home, or been forced to completely change their life. The world thought that, at least in Europe, it would no longer see the kind of crimes we remember from previous wars. However, Russia’s attacks prove that nothing has changed.

In Poland, people still talk about the war in Ukraine every day, but in other countries where I have worked for the past year and a half, this war seems very distant and fewer and fewer people remember it. So I try to tell stories from Ukraine for as many media outlets as possible.

I still have two images of the war in my memory. The first is from early March 2022. At the time, I was in Lviv, where thousands of refugees from other parts of the country were seeking asylum or traveling abroad. Life in the city was almost normal, except, for example, at the train station. One evening, during the curfew, I saw a family running through the streets. A grandmother with her daughter and granddaughter, who was clutching a doll tightly to her chest. Three generations of women fleeing the war.

The second is an image of a man who helped clean the interior of the Odesa Cathedral after a missile attack. The altar was destroyed, but the man stopped for a moment, put one small candle in front of it and lit it. He prayed and went back to work. This image of a small light in the midst of destruction became for me a symbol of hope and the will to fight, despite all that I see every day while working in Ukraine.

Yeva Sokolenko plays the piano on Christmas Eve. Kyiv, January 2023. Photo: Kasia Strek / Panos Pictures

A candle lit by a volunteer in the destroyed Transfiguration Cathedral. Odesa, July 2023. Photo: Kasia Strek / Panos Pictures

Lviv, March 2022. Photo: Kasia Strek / Panos Pictures

Ukrainian soldier Denys Kryvenko in a rehabilitation center. Lviv, July 2023. Photo: Kasia Strek / Panos Pictures

Marek M. Berezowski

Marek M. Berezowski is a documentary photographer and cultural anthropologist. He has been documenting the war in Ukraine almost from the very beginning.

In 2015, he worked a lot in Mariupol and Donbas, including the occupied territories. Since then, he has been working on the Donbass. Aftermath story, which explores the long-term impact of war and propaganda on the daily lives of civilians in the war zone.

The role of a photojournalist is not only to be a witness and an intermediary between reality and the audience, but also to help better understand a complex reality, to remind us of human rights and justice. Because of these views, I cannot imagine myself outside of Ukraine and the process of documenting the war against the Russian occupier.

I first visited Ukraine in 2005, and 10 years later I started documenting the war in Donbas. I arrived in Kyiv on the first day of the full-scale invasion. I spent more than a month in and around the capital: I filmed not only wartime Kyiv and the tragic consequences of Russian shelling of the city, but also Russian war crimes in Irpin.

Two months later, I came back to the same place to document the return to life and reconstruction. The victims of Russian war crimes in Irpin are still in my memory. Civilians were simply shot, it was no accident. I talked to the widows of the locals, and this is the most difficult experience. Death, which is always terrible and cruel, not only takes away one life, but also becomes a tragedy for the loved ones.

Another important issue for me is the suffering of animals. Like children, they are completely innocent creatures who do not understand what is happening around them, but suffer no less than people. I try to help them as much as I can.

A pillar of smoke over Kyiv after a rocket attack, March 2022. Photo: Marek M. Berezowski

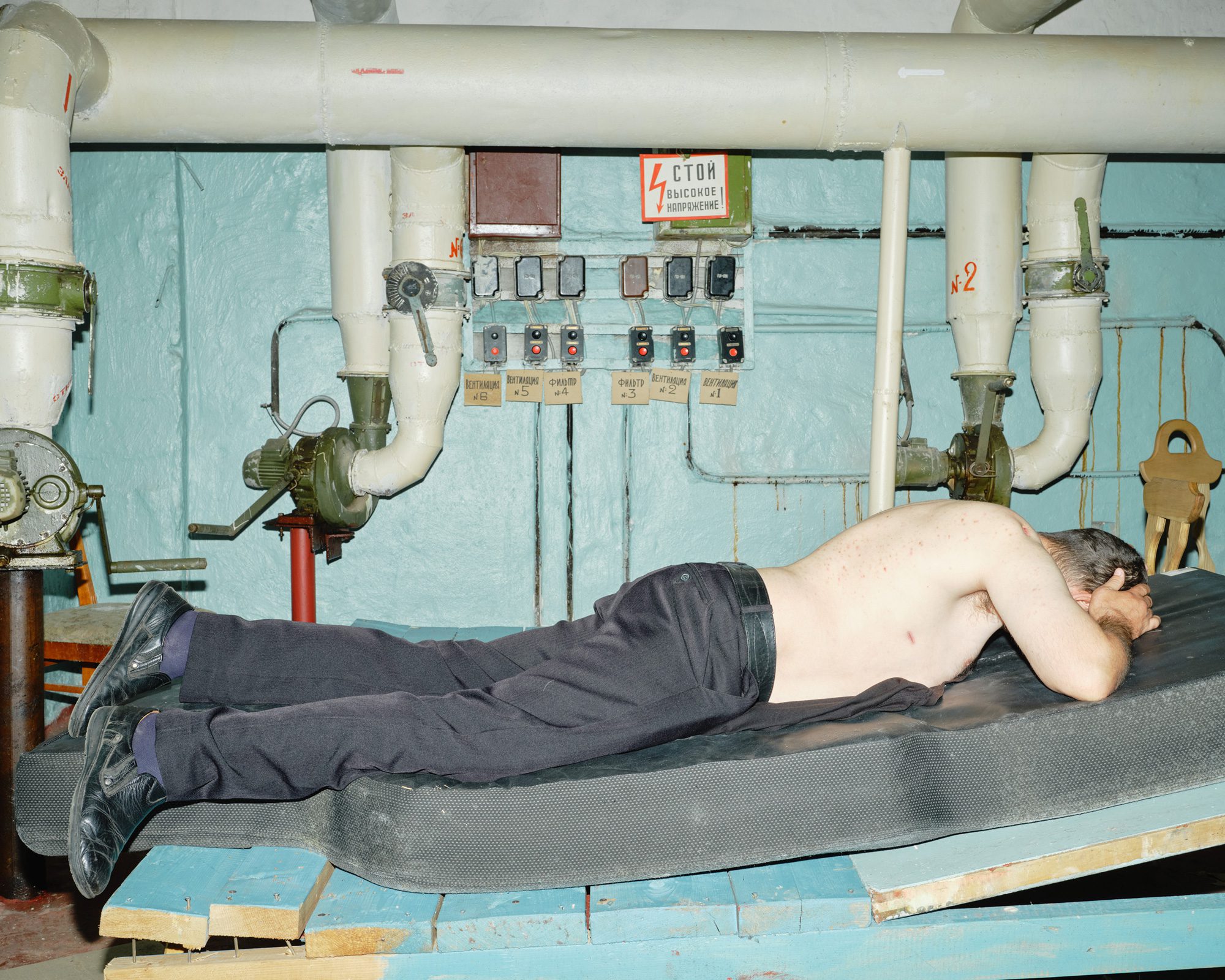

Civilians sleep in a shelter. Kyiv, February 25, 2022. Photo: Marek M. Berezowski

Ukrainian soldiers and a frightened dog during the fighting. Irpin, March 2022. Photo: Marek M. Berezowski

A man mows the lawn against the backdrop of destroyed houses. Irpin, June 2022. Photo: Marek M. Berezowski

Marcin Kruk

Polish documentary photographer, member of the Archive of Public Protest, an association of photographers documenting social activism in Poland. Kruk’s photographic practice revolves around long-term documentary projects.

In Ukraine, he is working on a photo series called No Tears Left to Cry, a story about what civilians had to go through, as well as the country’s rise from the ruins of war.

Today, when support for Ukraine is declining in Poland, as well as in Europe, and Russian propaganda is doing everything to antagonize our peoples, we need to constantly talk about the war to keep people interested in the topic, which should turn into continuous support for Ukraine. So, as a humanist and documentary filmmaker, I consider it one of my duties to be socially useful.

Since the first days of the full-scale invasion, I have focused my work on civilians and the various aspects of the war that affect their lives: migration, genocide, overcoming trauma, changes in society and culture.

But at the same time, it is also a personal story for me: in the 1940s, my great-grandparents were forcibly relocated from the outskirts of Ternopil to Poland. Since I was born 10 kilometers from the border with Ukraine, Ukrainians have always been present in my life.

I hope that one day my photos will become evidence of war crimes committed by the Russian army. I was shooting the exhumation of the mass grave in Izium on October 11, 2022 — I remember it as if it were today. It was winter, drizzling rain, fluttering police tape, and a constant feeling that a terrible crime had taken place here. I shot for half an hour, got back to the car, and started pounding on the steering wheel in tears.

But the hardest part for me is coming back from Ukraine to Poland. Every time I cross the border, I feel powerless. I’m returning to a safe place while my friends and ordinary people are still living under constant threat. Even in Poland, I have the air alert app turned on, and when I see the alert messages, I constantly feel fear. Only here, this fear is not about me: I am afraid that someone I know will die in a moment. It is also a fear for ordinary people. And when I read about new missile strikes, I feel fierce anger and powerlessness.

Borys is a combat medic and openly gay man who serves in a unit together with other members of the Ukrainian LGBTQ+ community. Kyiv, October 2022. Photo: Marcin Kruk

A missile fragment in the Izyum forest, October 2022. Photo: Marcin Kruk

A man demonstrates the position in which he was shot twice by the Russian military in a basement on Yablonska Street in Bucha, where he was held hostage along with local residents. Bucha, July 2022. Photo: Marcin Kruk

A balcony view of the theater stage used as a temporary shelter for refugees. Lviv, March 2022. Photo: Marcin Kruk

Wojciech Grzedzinski

For many years, Grzedzinski has been covering armed conflicts and their aftermath in Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan, South Sudan and Georgia. His work is centered on documenting the human condition and frank emotions.

In 2011–2015, he was the official photographer of the President of Poland. The photojournalist’s works have been recognized at such competitions as World Press Photo, Visa D’Or, NPPA, Sony World Photography Awards, Grand Press Photo. In Ukraine, Wojciech worked for The Washington Post and, more recently, for the Anadoulu Images news agency.

I first started reporting on the war in Ukraine in 2016. And since December 2022, I have been living in Dnipro, but most of the time I work near or on the front line. Sometimes I have the impression that press officers perceive me as an obstacle, and many colleagues give up trying to get access to work with the military or try to bend the rules. It hurts me that people do not understand what journalism and photography are and how important it is to inform about what is happening.

The consequence of this is a decrease in interest in the war in the West. And less interest means less assistance in many areas, from humanitarian to military.

For me, this war is personal. If Ukrainians hadn’t fought so hard, in a few years the Russians would have attacked Poland and the Baltic countries. That is why it is important to show and tell stories that affect both civilians and the military on a daily basis.

This war will change Ukraine forever. Millions of people were forced to flee their homes, and thousands lost their lives. There is no family that has not been affected by Russian aggression. I remember the smells of this war, the despair and uncertainty of a father who, with his son’s blood on his hands, waits for news from the operating room, the stories of people who survived the occupation, the stories of those who were raped and tortured.

In retelling their stories, it is important for me that people who lead a quiet life understand a little more why they should not be indifferent.

Iryna Maniukina plays the piano in her recently destroyed house. Bila Tserkva, March 2022. Photo: Wojciech Grzedzinski

Grain is burning after a shelling in the village of Zasillia in Mykolaiv region, July 2022. Photo: Wojciech Grzedzinski

A girl under the rubble of the Ria restaurant, Kramatorsk, June 2023. Photo: Wojciech Grzedzinski

Ukrainian soldier Serhiy from the 24th Aidar battalion in a truck on the way from a firing position. Donetsk region, March 2023. Photo: Wojciech Grzedzinski