Donetsk region is probably the hottest spot on the planet as of the beginning of 2023. Part of the region has been under occupation for more than nine years, but since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the battles for the region’s territory have become fiercer. Despite this, residents remain in towns and villages near the front line. Every day, volunteers risk their own lives to evacuate civilians. The Zaborona team visited the evacuation mission of volunteers of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine and tells what it is like to go to a front-line village, knowing that most likely, people will refuse to leave their homes.

Circle and cross

The base of the Ukrainian Red Cross Society of Ukraine in the Donetsk region is in one of the front-line cities [location not specified for security reasons]. At the entrance is a dilapidated and burnt building, and opposite is a huge crater from a rocket. Behind the iron fence, you can see several low-rise buildings and large white posters with red crosses hanging on the roofs.

A tall, slender man opens the gate to our car. Dmytro is a volunteer, and today we will go with him on an evacuation mission to a village on the front line. This area used to belong to the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). When hostilities intensified in the Donetsk region, the ICRC left and transferred the premises to the use of colleagues from the ICRC.

First, I ask whether it’s safe to put big red crosses on buildings that are likely to be a reference for targeting. Dmytro replies that the organization’s charter requires identification marks, and the Russians will hit without it if they want to. It has already happened: the last time, a rocket fell in a parking lot near one of the buildings.

Dmytro at the base of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine, during preparation for the evacuation mission. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Opposite the entrance to one of the buildings, a shepherd dog sits on a chain with a long nose and sad eyes. “This is Berda, a full member of the team. We evacuated her owners from the front-line village, and she reminded us of something so much that we decided to return specifically for her,” says the man in a bright red jacket. His name is Artem, and he is leading today’s trip.

Artem

Artem was born in Moscow, and in 1986, two weeks before the accident at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, he moved with his parents to Kyiv. During the Revolution of Dignity, he joined the Red Cross.

At the same time, in 2014, rapid response units appeared in the structure of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine — groups of volunteers who provide first aid to victims, evacuate civilians from dangerous areas, help rescuers during search operations, and deliver humanitarian aid. There are such detachments in almost all regions of Ukraine — 28 of them in total.

Artem and his family went to Georgia a few days before the full-scale invasion. On February 24, he bought plane tickets to Poland, and from there, he reached Ukraine. Artem went to the Military Commissariat, but they didn’t hire him. The first time he brought humanitarian aid from the west of Ukraine. Later, he again tried to join the Armed Forces. After yet another refusal, he returned to URCS.

Artem goes on trips like today almost daily. The rotation in the Donetsk region in the organization usually lasts 14‒17 days, but sometimes you can stay for two in a row because there is a lack of people. Artem and Dmytro did so this time: if everything goes well, they will return here in a week and two more. Volunteers in the Red Cross Society of Ukraine do not receive a salary. Some agree on regular vacations at work, while others try to work remotely and during rotations in their free time.

Artem (left) discusses with his colleagues the plan of the trip to Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

“We are now planning to go to Nikiforivka. This village is near hostilities. Fighting continues for Vasyukivka, a neighboring village. There is no communication there, but there are people who have stayed and plan to evacuate, and there are those who are still thinking. Some completely reject evacuation,” Artem explains, putting on a bulletproof vest with patches of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine.

The rapid response unit operates in a reasonably wide area: starting from the Ukrainian-controlled parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and ending with a patch of the Kharkiv region.

“At the end of autumn, we once again went to Bakhmut — requests for evacuation,” says Dmytro. “Roads were already blocked; they searched for how to get to one house for a long time. Suddenly, an air raid began. That was the first time I saw bombs being dropped by parachutes. When we picked up the man, we started to leave the main road, and at one of the turns, an artillery shell flew into the house in front of us. It was necessary to turn around and choose another road quickly.”

Now nobody goes to Bakhmut.

Cars of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine in Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Three days earlier, volunteers had taken out a man with limited mobility from Nikiforivka. His neighbor Maria, who was helping to pack things, agreed to think about evacuation. There is no mobile coverage there, and the only way to find out what she finally decided is to go to her place.

Artem warns that, most likely, she will refuse, and it will turn out that the trip was in vain. It happens often: people apply for the evacuation of a relative, volunteers come to the place, but people refuse.

“It’s hard to explain how we persuade them,” explains Artem. “They are all adults, and we cannot force them. We offer, motivate, and say that we will take them to safer places, that there is a place to resettle them, and that they will be cared for there. Not everyone understands this and still remains here. You will see everything yourself.”

A volunteer of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine is trying to find out where Maria’s house is, whom they will try to persuade to evacuate from Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

“The sign of the Red Cross will not save. Not in this war.”

Three cars — two volunteer buses and one of ours. Boxes with humanitarian aid are brought into the cabin of one of the buses in case they meet someone who needs it. Even though there is no water, electricity, gas, or communication in Nikiforivka, children still remain there — their parents refuse to evacuate.

Our convoy leaves for the road leading to Bakhmut. The roads in the Donetsk region are relatively good; overturned and burned cars are on the roadsides. Since 2014, the occupiers have not entered this zone, and the road is not fired upon by artillery. All these cars were involved in an accident. Cars crash into concrete blocks in the evening because turning on the headlights is dangerous due to possible guidance.

The road runs through the steppes, and you can see ruined buildings on the slopes — the villages of Orikhuvatka and Nikonorivka. “See the hill? Soledar is behind it. If you reach the top, you can see the destroyed city,” says Dmytro.

Children at an improvised roadblock on the way to Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

The road deteriorates significantly, and you can hear explosions. The car is quiet for a few seconds. The gaze glides through the landscape outside the window and stops on the windshield: through it, you can see the hood — on it is the red emblem of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine.

“This sticker,” I ask, “isn’t it a panacea against targeted attacks?” “It’s also a rule: the cars must be marked, and we must wear a special uniform,” replies Artem. “But if something happens, of course, it won’t save us. Not in this war.”

Nikiforovka. Now [at the time of the journalists’ stay in the village], Ukrainian military personnel are “training” here. Sounds of shots of the Armed Forces; it is difficult to describe: they are quite similar to shelling, but at the same time, different. The car reaches a small alley. There are only a few left in the village, it is not so easy to find grandmother Maria. We describe her to the only man we have met so far. He points to a small house on the other side of the street. It’s hard to believe someone really lives here: the building seems to be half buried in the ground, the windows are boarded up, the whitewash has collapsed on the walls, and everything is overgrown with lush bushes — almost a post-apocalyptic feeling.

Maria’s house in Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

“I will probably stay here to die.”

Dmytro calls into the room. It is damp and cold inside. Two beds fit in eight square meters. Underfoot are bottles of water, canned food, and various junk. A small older woman, wrapped in a shawl and several blouses, appears behind the door.

“Every day, the front is getting closer [closer to Nikiforivka],” Dmytro tells her. “Let it come,” replies Maria, “I need death anyway. I am sick, and there is no salvation. I don’t care; let them kill. I am waiting for death. I can’t talk about anything anymore, I can’t live anymore. God bless you for coming in.”

Later she adds: “Let them kill, let them do what they want. I don’t care anymore, I don’t have a life anymore. That’s how much I get sick — and I don’t die. God is not taking anywhere, it is not yet time. I don’t want to leave this house. I want to die here. My husband died here on the floor. There is a cemetery on the mountain. My daughter also died.”

Volunteers of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine persuade Maria to leave Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Volunteers of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine persuade Maria to leave Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Volunteers of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine persuade Maria to leave Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Volunteers of the Red Cross Society of Ukraine persuade Maria to leave Nikiforivka. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Maria hadn’t spoken to her son for a long time — it was Dmytro’s mention of the family that became decisive; she agreed to leave for him. But her neighbor Roman communicates with him — he knows the place where he catches a mobile connection.

Maria shows the volunteers the way to Roman’s house. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Artem and Dmytro talk with Maria’s neighbor Roman. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

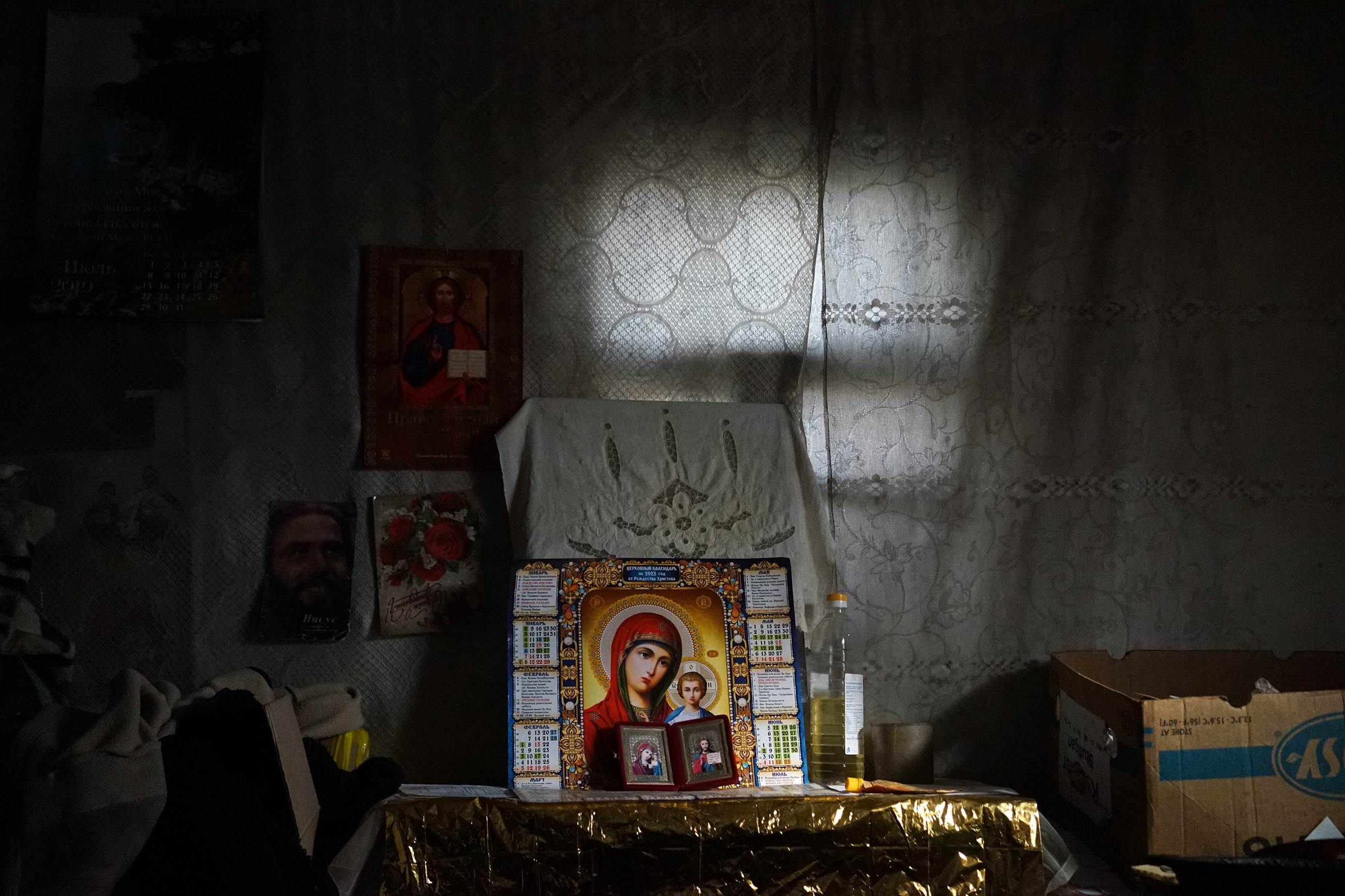

Maria enters her bedroom. Every corner has icons, and there is an old bed against the wall, a pile of clothes on it — so that it is warm to sleep. “Lord, grant me to return to this house,” Maria says. “You gave me this house, bring me back in the name of Jesus Christ. You can do anything.”

Maria collects things and documents. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Icons in Mary’s room. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

On the street, a dog runs around Maria, and her two cats are hidden somewhere from the explosions; three chickens and a rooster are walking around the yard.

“There are so many homeless animals here. Very, very much. We were driving recently and saw two already wild dogs finishing off a goat,” Artem says. “A terrible sight.” We try not to talk about Maria’s animals. Everyone understands that there is simply nowhere to take them. They, like Nikiforovka, remain behind in the rearview mirror.

Maria leaves her own house. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Maria with her son and daughter-in-law. Photo provided by volunteers of the Red Cross Society in Ukraine