Life Without a Father, a Fiance, and a Roof Over Your Head.

Zaborona Tells What the Year of the Full-Scale War Was for Ukrainians

Over the past year, Zaborona has systematically written about those facing the consequences of war daily: people and animals, children and adults, civilians and soldiers, vulnerable social groups, the LGBTQ community, and people with disabilities. Especially for the anniversary of the full-scale invasion, we have collected stories demonstrating from entirely different angles what it is like to be a Ukrainian at war. All of these heroes are united by loss and, at the same time, by the understanding that there is life after it, even if it is radically different from what was before.

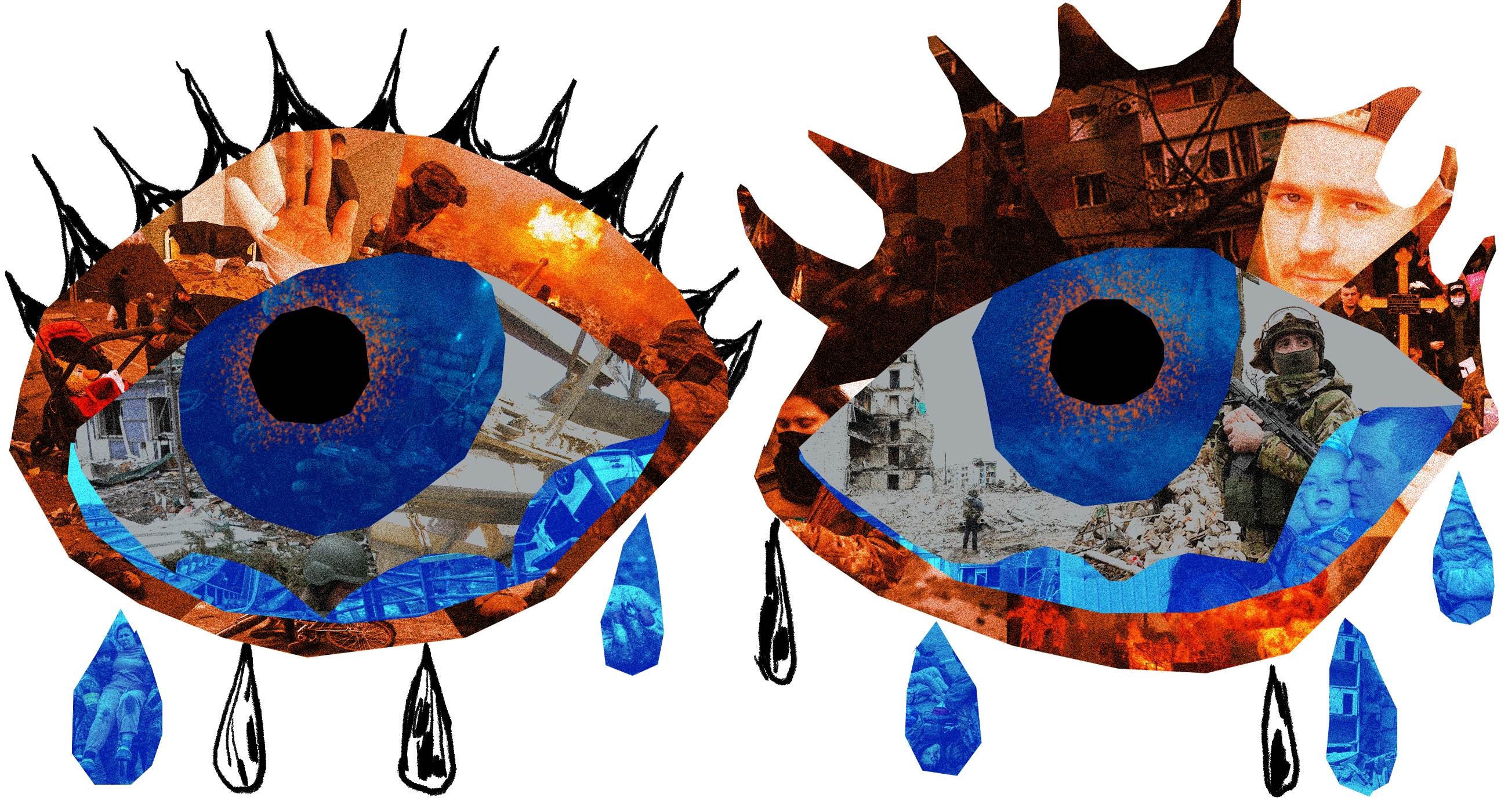

Anna Kiktenko: “At the funeral, I promised him that we will be together in all future lives.”

During the full-scale invasion, 25-year-old Anna combined her work as a make-up artist with volunteer work, and at the end of 2022, she was supposed to sign with her fiancé. But the wedding did not take place — two months before the appointed date, 26-year-old Maksym Tokarev died while performing a combat mission near the village of Opytne in the Donetsk region.

Anya Kiktenko and Maksym Tokarev. Photo provided by Anna Kiktenko

For a long time, I did not believe that war could begin, although Maxim constantly prepared and reminded me: the war was inevitable and Russia would not stop. Back in the fall of 2021, he asked me to leave Ukraine. In the last six months before the full-scale invasion, he was at “zero.” But then, of course, I didn’t believe it. But when everything became obvious on February 24, Maksym called: “See, I told you.”

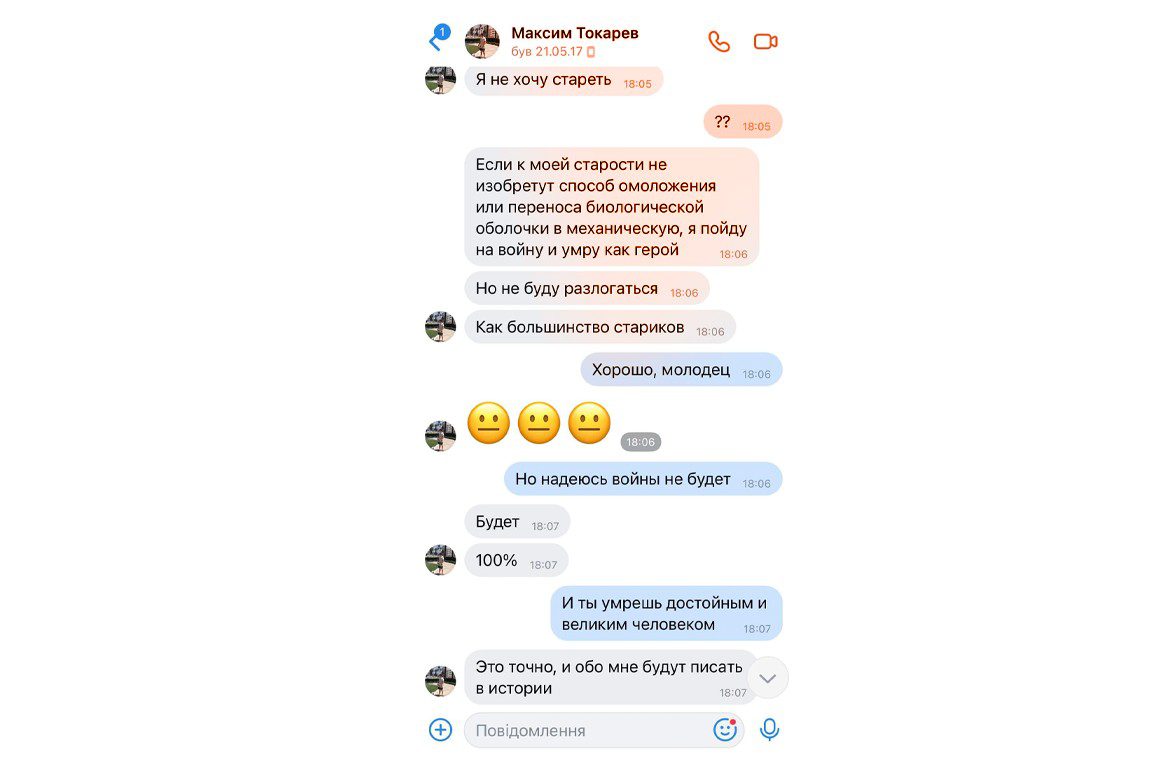

Texting between Anya Kiktenko and Maksym Tokarev. Screenshot provided by Anya Kiktenko

It was all of him.

Neither the Russians’ offensive nor the shelling of cities can compare with the news of Maxim’s death. On October 17, his subdivision went on reconnaissance to the village of Opytne, Donetsk region. Maxim did not get in touch, which had never happened before. After a week of silence, I received a message from his brother: “Is what they say about Max true?” Another hour later came the second: “It’s true, Maksym has died.”

Maxim taught me not to believe information about death or injury because there was always a threat that his phone would be hacked. Amid the flurry of panic and hysteria, there was hope that it was just a mistake. Already late in the evening, the information was confirmed. All night I stared at the ceiling and silently died somewhere inside.

We were together for 9.5 years. We met on the minibus — it turned out that Maxim studies at my school. We were friends for a year, and Maksym suggested we date after graduation. Then we went again by minibus. We can say that it was a sacred place for us.

In 2019, he proposed to me. And already in 2020, he faced the fact that he had signed a contract with the marines and would fight in the East. He wanted to change Ukraine for the better, be a politician, fight corruption, and build Kyiv. He explained his decision to join the army simply: only someone who has really done something for his country can be a politician.

Maksym Tokarev. Photo provided by Anya Kiktenko

I was against it at; first, I manipulated the divorce, but it didn’t work — he was a person who’s not changing his mind. I loved him, so all I could do was support him. It was his path, and he wanted to go through it so that he would have experience and that people would trust him in the future.

I saw him for the first time [after February 24] in the summer when he was wounded in the arm. It was the happiest day! This feeling — when you go to your loved one, and you will see him in a little while — cannot be compared with anything.

He told how his subdivision got out of the encirclement several times and how people died. All the time, it seemed that if he survived in such conditions, then everything would be fine with him. He inspired me to believe that it was not his destiny to die in this war.

I regret that when I had the opportunity to come to him, I did not do it — Maksym said that it was dangerous. Now I don’t care what he said. It was necessary to go and hug him, even if for two hours. The hardest part was living in the unknown and waiting for when the war would end, and we could finally become a family and have children, as we dreamed of.

Now there is no waiting, only the terrible unknown.

I hope that when people truly love, they will find each other even after death. At the funeral, I leaned over to him and promised we would be together in all future lives. When I got up, he seemed to smile.

Maxim always said that one should remain human and do good. He is gone, and I could close inside myself, but my conscience does not allow me. I feel that people need help. Some people advise me to leave everything, not to read the news. And I can’t — I should be part of this story. Maksym used to do all this, but now I need to understand many aspects of life in the country myself and support others, just like him.

After his death, Maxim’s family created an online petition to rename the street of the Russian artist [Vasyl] Surikov in his honor. Many people who disagreed wrote to me that permission should have been asked beforehand — they say that those who grew up on this street are used to it; it is so convenient for them. Someone says that we don’t have enough streets for each hero. It is stupidity. We need to get rid of Russia and the Soviets. Yes, heroes do not die, but we will die, and those who fought will be forgotten. Therefore, it is worth inscribing their names, at least in the history of the streets.

Mykhailo Obidets: “They dropped bombs purposefully because the Ukrainian flag was flying on the mayor’s house.”

A 71-year-old man lives in the village of Velika Pisarivka in the Sumy region, which is half an hour’s walk to the border with Russia. He has been working as a researcher at the Hetman National Nature Park for many years — and a full-scale invasion did not change that. In March 2022, enemy shelling almost completely destroyed Mykhailo’s house. Obidets believes he was saved by his late mother, who died a year before the war.

Mykhailo Obidets. Photo: Oksana Kovaleva

February 24 is my birthday. I just met the war on my 71st birthday. I was standing by the window, drinking a glass for my health, together with a friend. At that moment, we saw a column of enemy equipment: hundreds of military vehicles and tanks. We froze with hooch in our hands.

I am not superstitious, but I am not so skeptical about some omens now. Because it was on March 13 that my life was conditionally divided into “before” and “after.” I returned from work, fired up the stove, and carried firewood from the barn to the house. I heard how loudly and continuously the enemy was pounding the village with cannons, howitzers, and BM-21 Grad. It is the third week already. So we got used to it.

I had dinner and went to rest in the hall. It is what I usually do: I watch the news on TV and fall asleep to it. Sometimes, if I don’t press the remote to turn it off in my sleep, it works like that all night. And here, something went wrong around 11 p.m. I woke up and, for some reason, wanted to go to the next room, where my late mother’s bedroom used to be. She died in the fall of 2021 and did not live to see the war. My mother was in her 92nd year, we lived together, and I can’t even tell who took care of who: she tried to help me with everything. She was bedridden for the last year, so, of course, I took care of her.

And that evening, the legs carried me to my mother’s room. After the burial, I couldn’t go in there — everything reminded me, and I was choking back tears. Sometimes I looked in only because two kittens had chosen the room; then, I brought them food. Suddenly — a powerful explosion. It rattled so much that it stunned me.

Nothing is visible in the house: smoke and plaster all around. The hall caught fire, it hit my sofa. The roof came off. The pipe from the projectile went through the entire house and fell into the pantry, into a jar of honey. A portrait of Shevchenko, a shelf with books… But the icon survived. When I buried my mother, I left it on the table and thought I would clean it after 40 days. And then the war began — why take the icon out? Let it stand. And during the bombing, it didn’t even move.

I think the bombs were dropped on purpose because there was a Ukrainian flag on the mayor’s house. However, the house was partially renovated within a year. Slowly everything will be rebuilt, only need to be alive and well.

Our border community announced itself to the whole world precisely because of this. It was attacked a few minutes earlier than other settlements. It was heard about in the European Parliament because the head of the community Lyudmila Biryukova was invited there. She told the truth about the crimes in the border areas and that our people cannot be broken.

The belief that I will live out my days in Velika Pisarivka keeps me in this world. As a child, my mother fled the war twice: from Ryabushok in the Lipovodolin district to Trostyanets, then from there to Kharkiv. And after graduating from school (she was a zootechnician), she married my dad in Velika Pysarivka.

Here are my roots. My parents are buried here. Here I will end my earthly journey.

Mykyta Kozachynskyi: “During the war, I stopped dreaming — that’s very harmful.”

In recent years, 37-year-old Kozachynskyi has been developing an educational platform and nightclub Module in Dnipro (we wrote more about this project here). After the start of the full-scale invasion, the creative community of the cult space formed the “Module Squad,” which became part of the 128th brigade of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Kozachynskyi got there, and even before February 24, he decided to go to war.

Mykyta Kozachinskyi. Photo: Mykyta Kozachinskyi / Facebook

War, in simple words, is pummeling each other down: sometimes we give to them, then they give to us. At the level of the visual part, war is probably very similar to classic images from motion pictures. But emotionally, it is much deeper because you are a participant, not an observer.

I now participate in the war because when someone is robbing your house, you have to defend it. No matter how strange it may sound, the instinct of self-preservation sent me to war — because everything important to me is in Dnipro, Kyiv, and Ukraine. My biggest fear is to wake up in Russia one day and somehow have to live with it.

I don’t want to and can’t; I love freedom very much. And this is why the war is going on in general.

I knew as much about war as boys can learn about it — what weapons there are and how in theory, to use them. Although I am not a military man and have never been one, I am a good manager. And I went to war with the thought: if I am of little use on the battlefield, I can do a lot for others. Likewise, I had no idea what it was like to be in the military because I am very chaotic, and it was difficult for me to imagine myself in a structure with a lot of order.

Mykyta Kozachynskyi (far right). Photo: Mykyta Kozachinskyi / Facebook

Today, my job is to keep the front line at zero. We fight with the Russians every day because every day, they come at us like a wave with tanks and people. Now we are not far from Vugledar [Donetsk region], one of the hottest spots in Ukraine, and there is very, very heavy fighting. So sometimes, all I do is wake up and shoot the cannon.

I stopped dreaming during the war — that is very harmful. I have to do my job and focus on it. I have to work, not dream. But there is a place for fear in war because people who were not afraid have already died. In battle, if you are fearless, it can end badly because you have to be careful. And for this, you need to feel fear.

I felt it the most when I lost someone I knew. Fear because you can’t do anything more about it.

Mykyta Kozachynskyi and Bilka. Photo: Mykyta Kozachinskyi / Facebook

The war changed me mainly from the outside — my beard turned very gray, and I, too, turned gray. A lot of things hurt, and a lot of fatigue appeared. I began to be happy about ordinary things: a clean bed, a hot shower — I feel more joy from this than before.

In the middle of the war, I got a dog because we lived in a house with many abandoned animals. All the locals left, and she came to us for food. I won her trust for a long time. At first, she did not approach, and then even lay in the sleeping bag next to me. I named her Bilka (Squarrel). She was very worried during the loud shelling, so I took her to Dnipro, to my mother. Now they worry together.

Yulia Okhrimenko: “When the younger son turned three, the husband celebrated his birthday in the cell.”

At the beginning of March 2022, the occupiers captured Yulia’s husband, 37-year-old minibus driver Andriy Okhrimenko (Zaborona wrote about it in more detail here). The Russians found photos of military equipment in his phone and promised to release him in a few days. However, the man is still in captivity, and in addition to his wife Julia, two more children are waiting for his return home — 19-year-old Andriy and three-year-old Sashko.

Yulia and Andriy Okhrimenko. Photo courtesy of Yulia Okhrimenko

During these 11 months, I actively tried to bring my husband home. I wrote letters to the president four times, including private notes, so that they would reach the addressee. I also sent a letter to the ombudsman, Dmytro Lubinets. But I did not receive an answer.

The only one who reacted was the National Information Bureau. They answered that Andriy is alive and is in the “Oleksiivka” correctional colony of the Belgorod region. The Russian side and the international Red Cross officially confirmed this.

But I was finally convinced only on the eve of the New Year when a resident of the city of Romny, who had been released from captivity, called and said that he had spent eight months in a colony with Andriy. He told me that my husband does not know anything about his family and is very worried about it. He misses his children. When the younger Sashko turned three, they somehow celebrated his birthday in the cell.

I believed the former prisoner’s words more than the Russians’ official answers. And there are reasons for this: before that, through the paid electronic system of Russia, I scattered letters in four pre-trial detention centers with pictures of children. The content of these letters was purely family — how much we love Andriy and are waiting for him at home. I also paid for a return letter but received an official answer: Andriy Okhrimenko is not in one of the institutions.

Later it turned out that the man did not see those letters — none reached him.

I found a Russian volunteer organization on the Internet that promised to pass on the news to Andriy. It was suggested to me by a Russian lawyer — I also reached out to him via the Internet. She turned to him because there was nothing left to lose. Everyone seems to work for us [in Ukraine]: the police, the prosecutor’s office — we are constantly in touch with them. But the husband is still not at home. It is better to do something than to sit and wait.

On the other hand, I need to figure out if I’m doing the right thing. Among the recently released hundreds of prisoners were the husband of my acquaintance. At the time when I was actively seeking the return of Andriy, she did almost nothing. But for some reason, it was her husband who was released. However, he is also a civilian, like Andriy, and had nothing to do with military operations.

I am in despair, but I do not give up. I hope that the family will still be together. We live in our house now. In fact, in March, it flew into the air. We patched the premises a little so there was a place to live.

Sashko has already turned three years old. He does not remember his father at all. To all the pictures of unfamiliar men, he asks: “Is this my dad?” When the recent prisoner exchange occurred, I said that his dad would be coming home soon, too.

I regret it because the child has been walking around for a week asking where his daddy is.