Pascal Gielen is a Belgian sociologist who studies the relationship between culture, politics, and capitalism. Gilen’s books are translated into Ukrainian, and he comes to Kyiv during the war to build joint academic projects to study, among other things, the decolonization of Ukrainian culture. Zaborona editor-in-chief Kateryna Sergatskova met with Gielen and discussed why some European countries are delaying the supply of weapons to Ukraine due to the politics of fear, whether the cultural boycott works, and how humanity can begin to emerge from the era of endless crises.

For what purpose did you decide to come to Ukraine?

I have several reasons for being here. Over the past 6 years, I have built a very strong relationship with Ukraine, considering the number of my publications here [translations of my works into Ukrainian]. I also feel very emotionally attached to Ukraine and, at the same time, responsible.

I have several ongoing projects, including a research grant for Europe called Horizon. It started even before the war, and the main problem to which it is dedicated is how the cultural space can develop political engagement and democracy. I’ve been doing this for 20 years — research on culture, politics, and civil society. So now I’m contacting universities and cultural organizations to see if they can be my partners. It is part of my main — academic — life.

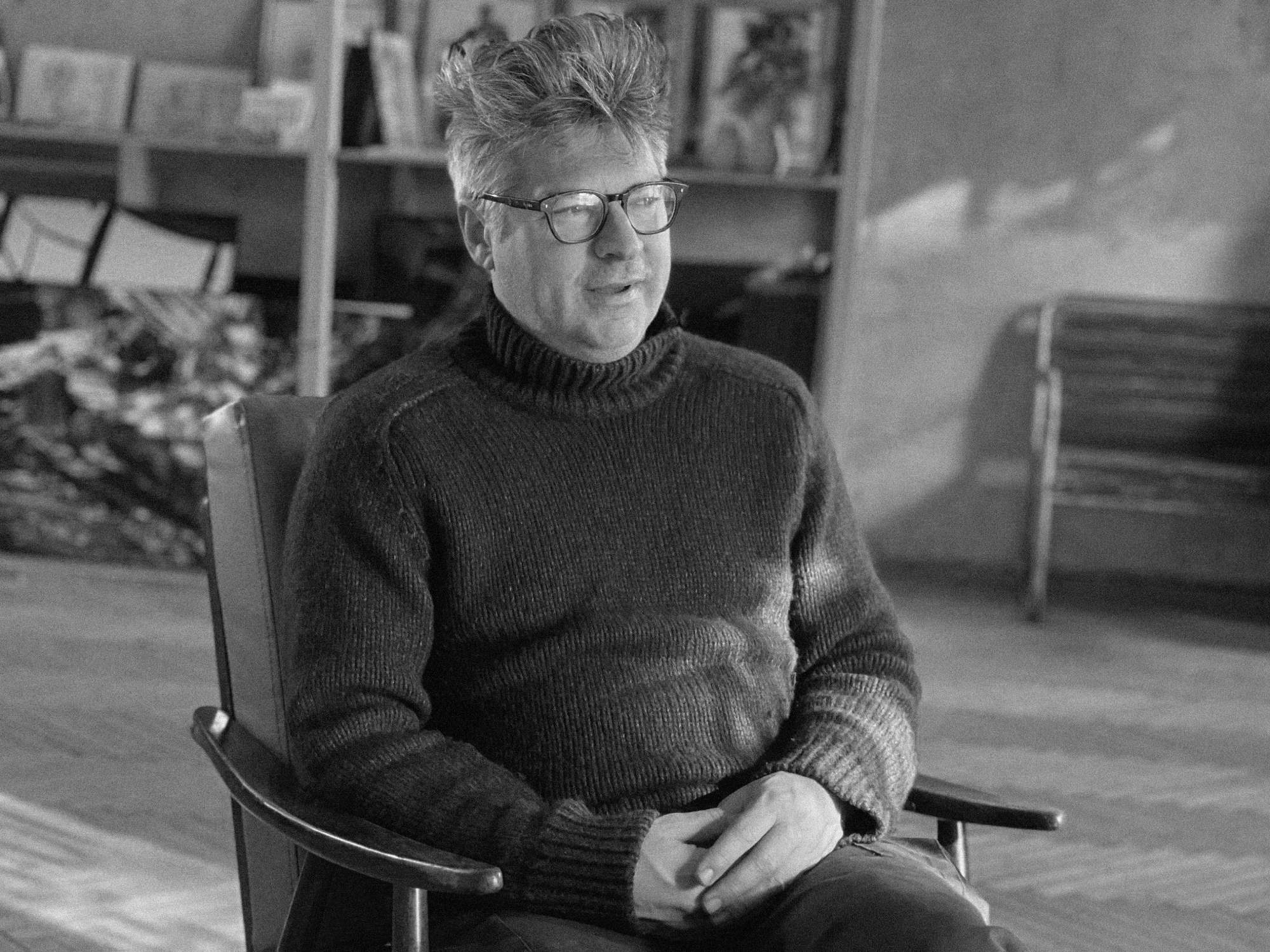

Pascal Gielen, photo: Yevhen Zhulay / Zaborona

The second thing I do is work with a research group in Belgium. The project is called Culture Commons Quests. There are 33 people on the team, many artists, activists, as well as a director. We shoot the interview; many speakers — primarily artists — are very interesting. First, we have two key questions: How do they think culture works? What can be useful or harmful? The second question is whether culture can be useful. For example, [can culture be influential] after the war in the process of decolonization, how do they think they can rethink history? We are setting the agenda for the post-war era.

You are in Kyiv during a full-scale invasion. Are you afraid of danger?

Sounds like a macho answer, but it’s not. Yes, it is strange. And this is a purely psychological and emotional attitude towards oneself. I can give it a rational analysis. I think there is a huge problem with what I call the politics of fear. The politics of fear is that people are instilled with fear by mass media, politics itself, etc. This policy forces people not to act as they would in ordinary, familiar circumstances — and this is a very problematic indoctrination.

It is typical, and I would even say, a right-wing conservative policy followed by many political parties in the world. For example, they were afraid of Islam. Or fear of a virus pandemic. It is a kind of constant fixation on fear.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

If it is somehow related to hate speech, then I think it is one of the methods of politics when people are intimidated so that they do not go to Ukraine, for example.

Even in a broader sense. It is about the fear of supplying weapons to Ukraine because of the fear of consequences. Yes, this is the rhetoric of the mass media and politicians, for example, in Germany — or the intellectual layer there. So, we have two discourses. One of them is pacifism. But the other is pacifism through fear. And, I think, sometimes, it is correct. Of course, we need to be wary of escalation. But you see, the arguments are based on fear.

At the beginning of the war, this was pan-European rhetoric. In my country, Belgium, many say: “We cannot attack. We can’t even introduce a no-fly zone because of the economic consequences.” That is, they are afraid precisely for economic reasons! Not for their own lives or your lives here in Ukraine, but because of the fear of financial loss. For example, such a discussion is currently underway in Belgium — the country refuses to boycott the trade of Russian diamonds. Because they say that if we do this, other countries will continue to trade diamonds and get more profits. It’s a problematic policy, and yes, it’s for economic reasons. But they package it in the politics of fear.

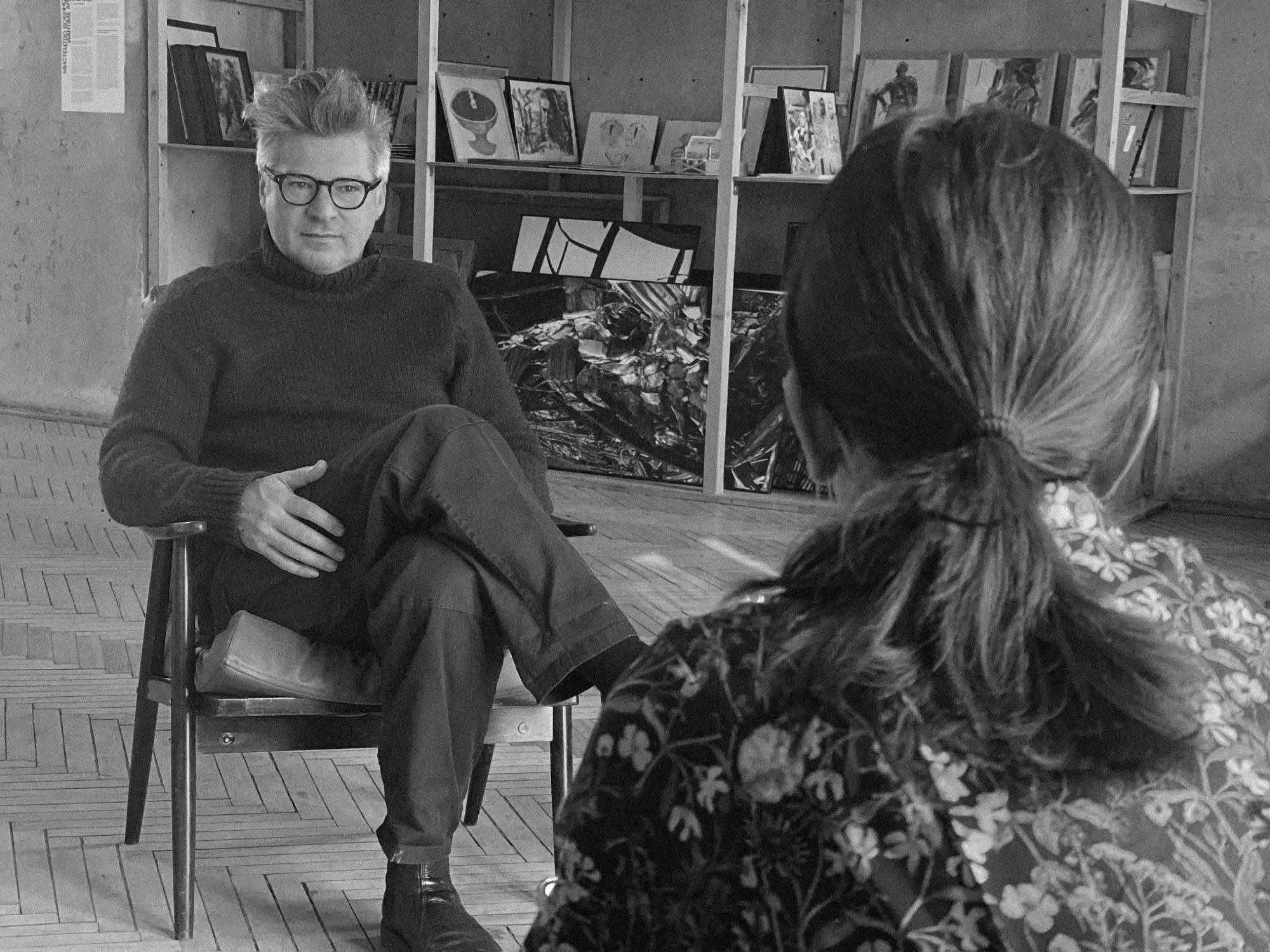

Kateryna Serhatskova and Pascal Gielen. Photo: Andriy Bystrov / Zaborona

Similar processes are ongoing in Ukraine. Despite the full-scale war with Russia, some Ukrainian mass media do not give up Russian-language versions of their sites. As a media manager, I understand their business logic — they will lose half of their traffic.

I didn’t know that, but it’s strange!

There are no rational solutions. I think now we should act more antagonistically, emotionally and, fundamentally, even ideologically. In Western Europe, a particular ideology to which we are so accustomed and neoliberal in its essence is the ideology of profit. It is a real political, no, even ideological problem! And we need to eliminate this idea that, say, a neoliberal free market system is the solution to peace. It is a decision for our well-being, nothing more.

There was a clear thesis — and it is returned to again and again — that our need is to grow economically. That we need to grow. And competition is a good thing for living standards, quality of life, etc. I think we really should get rid of this belief system.

And there is a way out. It is what I and several other people, intellectuals, and politicians are promoting in Belgium and Europe. It is a belief system that values social relationships, not economic ones. [According to her], economic relations should be based primarily on human needs and social concerns, not the other way around! It’s about solidarity and positivity so that you give something back when you get something. It is the theory of communities. And I think more and more people feel and are convinced that we should go in this direction. I have nothing against free markets and nothing against economic theory, but it all has to be different. It is what we are trying to organize. I am very practical and specific in this direction. Yes, I am currently working on such a concept for the Flemish government.

Kateryna Serhatskova and Pascal Gielen. Photo: Yevhen Zhulay / Zaborona

In your opinion, is there enough social (rather than economic) solidarity in the European Union? Do people really understand what to do to overcome neoliberal relations?

I will quote the Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci. He said that we live in an organic crisis. It means one crisis after another: climate crisis today, economic crisis, financial crisis, pandemic crisis, climate crisis again. It is extraordinary, and he argued that this is a typical historical moment where we see the system still functioning. But we also know that it no longer works. And we act and continue to act because we have no idea about anything else. By going through these crises, again and again, people become more and more aware.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Do you think cultural diplomacy and the promotion of Ukrainian cultural projects work? Does it raise awareness of the war or explain something about it?

It works. We are hosting a massive exhibition of Ukrainian art in the Antwerp Museum of Modern Art. For Western Europe, this is what makes Ukraine and Ukrainian culture closer. Also, videos made by the media, documentaries, etc., are very useful.

I think it is necessary to respond positively to the decolonization process. I’m not an expert on Ukrainian culture, but I think Russian culture dominated — for example, the Russian language in everyday life and the literary language in particular. My Ukrainian colleagues admitted that only three months ago, they stopped speaking Russian to each other. And, of course, symbolically, it is very important. So my question is, what will the process of decolonization be? We are pushing out the entire Russian culture. Logically, there is a huge gap — and we should fill it positively. But decolonization is a negative process. I think that artists have a huge task to rethink, reformulate, and fill this gap.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

What can be an alternative?

Artists and intellectuals in Ukraine see what is wrong in the West. Also, politicians learn from what goes awry. And then another system is invented — it is also called the “third norm” — between communism and capitalism. I am still determining what it will look like, but it is essential. It is necessary to start it — and not start with the government and politicians. It should begin with civil society, with building a solid community.

Let’s talk about decolonization in more detail. Activists cancel the Russian “Swan Lake,” or Pushkin, or Dostoevsky. What do you think about it: does it work or hurt?

I think it’s good. In wartime, we have to understand which side we are taking. One example from the Museum of Modern Art in Antwerp decided to sever all official relations with Russia. But they stay in touch, and that’s important too. And officially — in the boycott. And remember that in Russia now, there is a very weak, but still, opposition. I think, at some point, we have to help them.

There are people [in Russia] who think differently. Maybe they don’t raise their voices enough, I agree. But the Kremlin has opposition. I hope they get a boost and make a coup in their country. And then we should support them. We should not just decolonize Ukraine but develop some other culture. Meanwhile, boycotts, boycotts, and weapons. Boycott culture.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

In Ukraine, there is an opinion that the culture during the war is out of date. Can you describe your vision of the role of culture in wartime?

Culture and art are not the same things, and it is vital for me to say that. Of course, art plays a significant role because it gives meaning. It gives sense to culture. For example, when you read a novel about a gay relationship for the first time, you get a new perspective. You see that other people can give meaning to love relationships differently. It is how art works for me. Therefore, in this sense, I believe that culture is definitely on time. It plays a fundamental role in the redesign of the nation, the redesign of the country, and this is again connected to my fundamental question: what to fill the gap after decolonization?