The Influence Will Go Away with the Speakers: How Central Asian Countries Are Abandoning the Russian Language

Central Asia is one of the few regions in the world where Russia is still actively trying to control the language policy of the countries. However, since February 2022, more and more post-Soviet states have embarked on the path of developing national languages.

Journalists from local media with the support of the Media Network tell us how the process of learning national and Russian languages in Central Asia is currently organized, why activists are primarily engaged in the development of national languages, and what are the ways to do this.

Tajikistan: Russian as a promising language

In Tajikistan, Russian is considered the key to a successful career and a means of access to modern literature and technology. Although English is much more promising in this regard, learning Russian is more affordable in Tajikistan. In addition, many families assume that after school, their children will study at Russian universities or later go to Russia to work.

After school, except for a small number of children, graduates cannot speak Tajik fluently. Learning it on their own is also difficult: In 2023, Tajik language courses could be counted on the fingers of one hand, and an hour of classes cost almost $20. And the language teaching system has not been formed: schools and courses teach literary Tajik, which is very different from modern spoken Tajik.

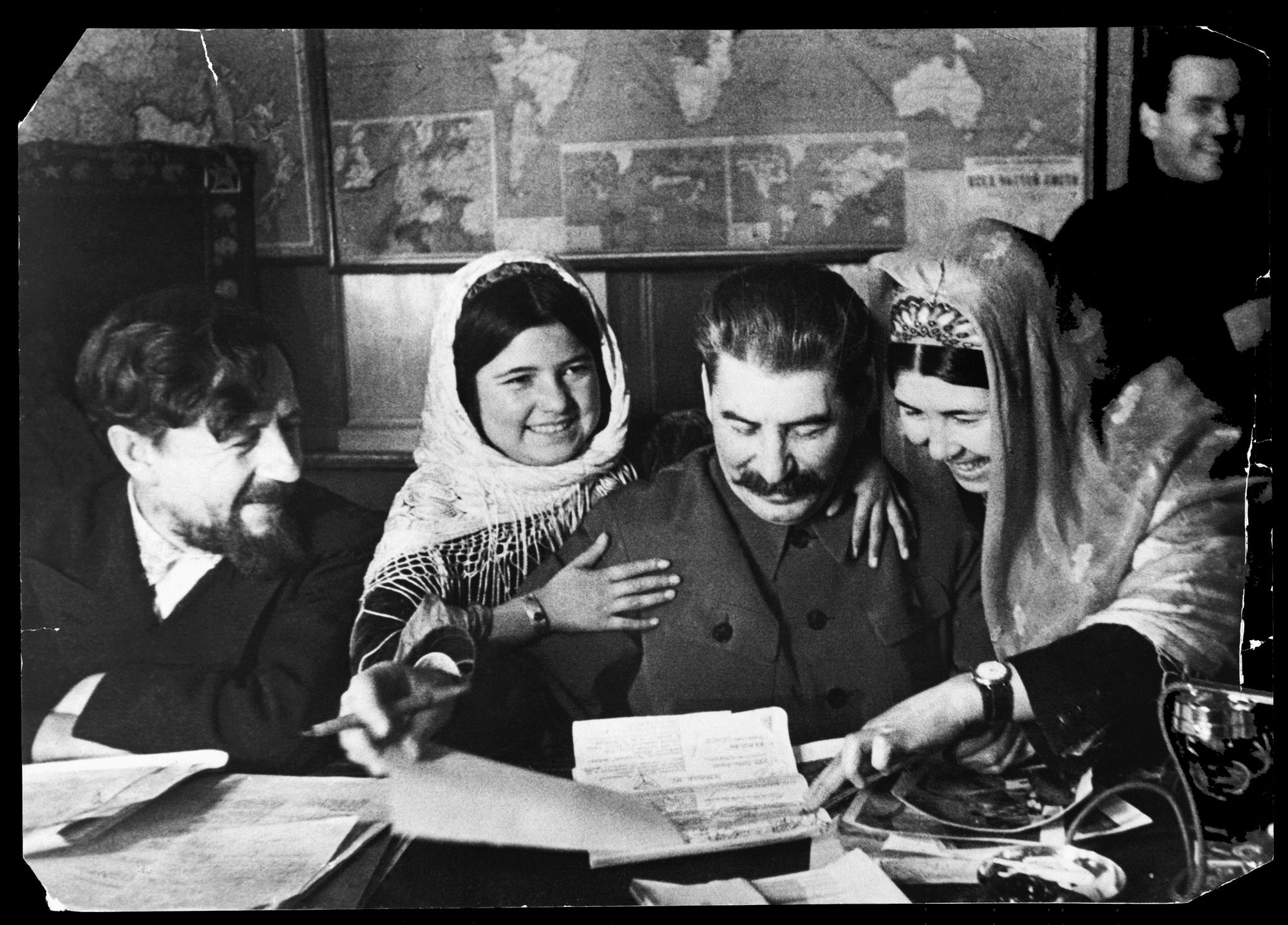

Soviet leader Joseph Stalin autographs photographs for 11-year-old members of a farming collective from Tajikistan. Moscow, December 11, 1935. Photo: Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

Why is it easier for students to speak English and Russian than Tajik? How does the Internet affect this? What do the authorities say about the problems with learning Tajik? Read more about this on Your.tj.

Kyrgyzstan: getting out from under Russia’s language pressure

At the end of 2023, Kyrgyzstan adopted a law on the state language, which obliges civil servants, MPs, teachers, and healthcare workers to speak Kyrgyz. Russian officials and propaganda outlets have called the law “undemocratic” and oppressive to the Russian language in Kyrgyzstan.

But the officials still don’t know Kyrgyz well, as evidenced by the language tests they have been taking for three years. “There are very few who passed at the A1, A2, B1, B2 levels. Among them, it was our Kyrgyz who failed. Because they were initially focused on Russian [in their work],” says Kanybek Osmonaliyev, head of the National Commission for the State Language and Language Policy. He is an ally of the president and suggests giving officials time to improve their Kyrgyz language skills — otherwise, according to the new law, they must be fired immediately.

According to the 2022 census, about 4.4 million people in Kyrgyzstan, with a population of almost 6.7 million, speak Kyrgyz. And there are more and more people who would like to learn the language. Activists are helping to develop the language and instill a love for it.

Since 2013, the Balastan project has been operating in Kyrgyzstan, publishing children’s books in Kyrgyz. And in 2017, Bugupress appeared, translating world bestsellers into Kyrgyz: books on business, economics, and fiction. The country also has the REC 55 studio, a team of enthusiasts who dub films and TV series in Kyrgyz, and the DevKurultai IT community, where you can learn to program in Kyrgyz.

Read more about how the Kyrgyz authorities are trying to free the national language from Russian pressure in Kloop‘s article.

Kazakhstan: activists are engaged in language development

The issue of language in Kazakhstan is one of the most conflict-ridden today. Language-related scandals periodically occur in the country, language has become a major component of the rhetoric of politicians with a national-patriotic agenda, and arguments for strengthening the position of Kazakh are becoming increasingly stronger.

Meanwhile, the main problem is obvious: over the decades of independence, no state manager has been able to cope with the managerial challenge and teach the society the Kazakh language (both schoolchildren and adults), notes Factcheck.kz.

Enthusiastic activists are trying to change the situation in the country. For example, writer Kanat Tasibekov created his own methodology and wrote the book Situational Kazakh, which helps anyone learn the language and founded the Kazakh language club MӘMILE.

At the same time, Tasibekov himself began learning Kazakh only at the age of 50: “I was ashamed that I was Kazakh and did not speak Kazakh. A doctor of philology asked me: “Didn’t you have any shame before you were 50?” I answered: “Before 50, I had other priorities. I had to earn money, raise my children, marry my daughter, marry my son…” he explains to Respublika.kz.media. “Learning a language is a lot of intellectual work. It requires both time and resources.”

Signing friendship treaty between Russia and Kazakhstan, March 1992. Photo: Sergei Guneyev/Getty Images

Turkmenistan: the success of language separation

Turkmenistan has advanced further than other Central Asian countries in revitalizing the national language: in 2020, only 18% of the country’s residents were proficient in Russian to some extent. On the one hand, the policy of Turkmenistan’s President Saparmurat Niyazov (who led the country from 1985 to 2006), along with the difficult socio-economic situation in the country, led to a massive outflow of ethnic Russians and the Russian-speaking population. On the other hand, a radical language policy worked.

The key moment was the transition from the Cyrillic to the Latin script. The process was accompanied by massive propaganda in the media. Speaking of the media, only one Russian-language newspaper was left in the country. The reform also affected education: despite the declared policy of trilingual education (Turkmen, Russian, English), Russian-language schools and university curricula were eliminated.

Turkmens hold Turkmenistan flags as they attend a newly-elected President Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov’s oath ceremony 14 February 2007 in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan. Photo: MUSTAFA OZER/AFP via Getty Images

Read the Factcheck.kz analysis to find out whether the influence of the Russian language in Turkmenistan has changed since the authorities declared in 2013 that it is important to learn the official languages of the United Nations, including Russian.

Uzbekistan: one step forward and two steps back

Uzbekistan is one of the Central Asian countries that planned to switch from the Cyrillic to the Latin alphabet. The process began in 1993. But while its neighbor, Turkmenistan, succeeded, the Uzbek authorities kept postponing the deadline: from 2000 to 2003, then to 2010, and now to 2023.

Authorities managed to publish some school textbooks in the Latin alphabet. However, there is a nuance: young people who do not speak the Cyrillic version of Uzbek have been effectively cut off from the world’s literary heritage, as very little fiction, including classical works by Uzbek authors, has been adapted into Latin.

Although Russian is not an official language in Uzbekistan, it still prevails in large cities, retains a position in business and science, and the stereotype that education in Russian is better than education in Uzbek has been reinforced in society.

People vote at home in Uzbekistan’s presidential election in Tashkent on July 9, 2023. Photo: VYACHESLAV OSELEDKO/AFP via Getty Images

Russians are an aging ethnic group

The number of Russian speakers in Central Asia has been steadily declining over the past 30 years, and this is a natural process. “We are confidently moving into a future where very few people will speak Russian, concentrated in the largest cities — in the conventional Almaty or Bishkek. The rest of the cities will speak national languages, and this is normal, it’s natural,” Carnegie Center expert Temur Umarov tells Kloop.

In addition, Russians in Central Asia are an aging ethnic group. Their average age is 38-40 years old. So the logic of this scenario is that the influence of the Russian language will go away along with the carriers of Russian identity and culture.

However, in practice, the dependence of the Russian language on the number of ethnic Russians is not so direct.

Ways of bans, compromises, and cooperation

Journalists from Factcheck.kz emphasize that Turkmenistan and Latvia have implemented a policy of strict restrictions on the use of Russian. Thus, in these countries, the state languages are already or will soon become the only languages of education (from kindergarten to high school).

This approach creates a so-called language nest, an environment where all adults speak the target language with children from a young age. If it is later used in universities and workplaces, the language moves from the everyday sphere of use to the professional sphere.

In this case, on the one hand, countries will implement many government programs to develop the language, and on the other hand, they will support Russian in various ways to maintain good neighborly relations with one of their main economic partners, Russia.

Success in revitalizing the language is based on the productive interaction of the government, experts, and civic initiatives. The state provides the legislative framework and funding, while experts and activists assess the needs of society and the level of readiness for certain reforms.

The key to successful implementation of any language is to create positive motivation for learning and using it. The language must be made necessary, useful, and prestigious. Effective planning is usually neither quick nor popular among all segments of the population. Moreover, these measures will not bring easy political points to their initiators. Changes will occur slowly, so it is much easier to use the language issue to play on populist sentiments.