On September 21, the world celebrates the annual International Day of Peace. In Ukraine, NGOs commonly arrange demonstrations in honor of the day, such as the NGO ‘STAN’. This organization advocates for values of human rights, equality, diversity and inclusion, and develops the civil sphere by attracting youth involvement in the creation of participatory democracy. ‘STAN’ operates in Ivano-Frankivsk, but the ‘Events for the International Day of Peace’ demonstration took place in fifteen cities and towns across Ukraine. Zaborona journalist Polina Vernyhor visited one of these demonstrations and explains how it went and why these sorts of events are needed.

‘Events for the International Day of Peace’ was organized by the youth organization ‘STAN’ with the support of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

People – mostly youths – have gathered in a small room, dominated by a big round table in the center. They’ve come to the offices of the youth human rights organization ‘STAN’, in order to talk about the world. ‘Events for the International Day of Peace’ is one of STAN’s biggest projects, a series of events taking place across 15 Ukrainian cities and towns. These events encourage anyone interested to discuss the state of the world in their own communities, regions, countries, and the world as a whole.

“It’s important for us to attract, in particular, ordinary people. In other cities, we place this table in the middle of the street, in their central squares. That’s how we engage regular passers-by who may not have had morning plans to visit some event and talk about the changes they would like to see around themselves, what problems they see and what resources they would need to solve those problems. This is very unusual for people, but may of them readily agree to this sort of format,” explains the designer of educational problems for STAN, Yuliya Lyubich, to us.

Yuliya Lyubich

“One of the other aims of this sort of format is to give people a chance to speak and listen to others,” adds STAN’s program coordinator Valeriya Vashkevych. “It’s very important for people to have a place where they can talk about their own views without judgement because they said something ‘incorrectly.’ People who are listening become rather more calm, open-minded, and productive. This reduces tension in society.”

Valeriya Vashkevych

“One of the other aims of this sort of format is to give people a chance to speak and listen to others,” adds STAN’s program coordinator Valeriya Vashkevych. “It’s very important for people to have a place where they can talk about their own views without judgement because they said something ‘incorrectly.’ People who are listening become rather more calm, open-minded, and productive. This reduces tension in society.”

Without any moderation, but with a few rules

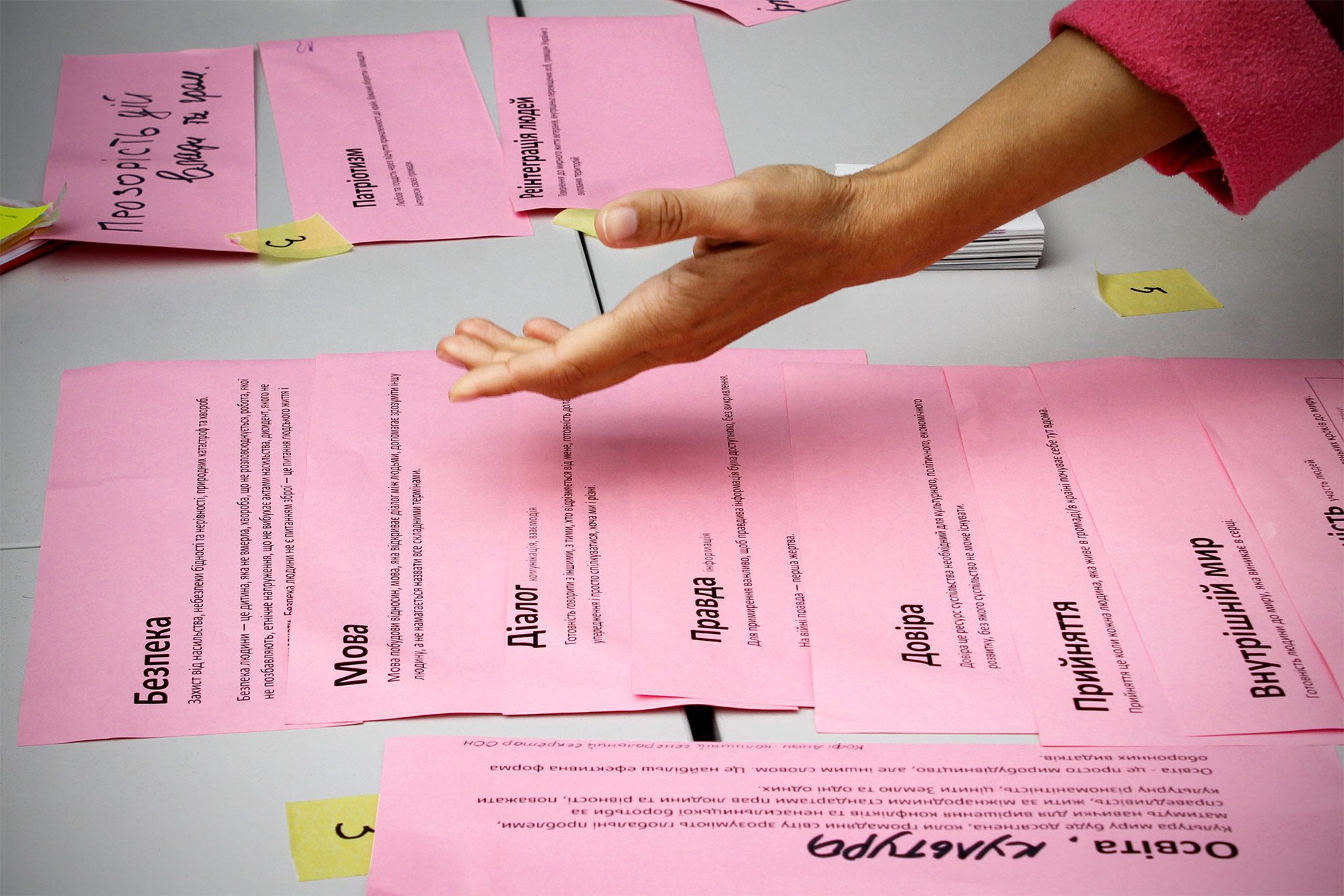

The “dialogues” work like this: people gather at the round table, on which 16 cards with different topics about the world’s development have been laid out.

These topics include dialogue, security, internal peace, language, truth, responsibility equality, the world’s economy, and law. These cards park the discussions – participants offer to create a given hierarchy out of these cards, from the most important to the most meaningful. If that doesn’t seem like enough, participants can add their own suggestions. Once this hierarchy is created, the participants discuss why some topic may be more important than another, and listen to the thoughts of the rest.

Photo: Oleksandr Stashevskiy / Zaborona

There’s no real moderator as such for these discussions, but there are facilitators – active but objective participants of this process. Valeriya Vashkevych explains to Zaborona that these facilitators cannot limit what the participants say, but they can set boundaries around the raised issues.

There is, however, one golden rule for these talks – each participant should feel safe.

“Our task is to create an atmosphere where a person can feel free to express their own position, even if it’s counter to the positions of other participants,” says Vashkevych.

She believes an ideal end to one of these “dialogues” involves participants with very different views on a given problem shaking hands, since that indicates that they were able to listen to each other, and that they as a whole were pleased with the discussion.

Most of the time when hosting these dialogues, the organizers invite local authorities to the table as well. This is so that the questions people have find answers, and so that problems don’t just stay in the realm of discussion but move towards some sort of resolution. Authorities usually ignore these invitations, but sometimes do take a seat at the same table with their constituents. In Ivano-Frankivsk, however, local authorities ended up ignoring the invitation.

Peace isn’t just a word

Svitlana Tarakhkalo participated in the “Open Dialogue” event in four towns across Ukraine. The words ‘peace’ and ‘reintegration’ probably mean more to her than most Ukrainians. In 2014, a pregnant Svitlana, along with her husband and two children, were forced to flee from their native Stanytsia Luhanska in Luhansk region.

The Tarakhkalo family first moved to Odessa, where they lived with relatives for a while – but once it became clear that there was no way back to their hometown, they began to look for more permanent accommodations. This was difficult, since many internally-displaced people lacked jobs and the ability to make monthly rent. As a result, landlords held consistent stereotypes about internally-displaced families, especially those with kids.

Stanytsia Luhanska after a bombing, July 12, 2014. Photo: DOMINIQUE FAGET / AFP via Getty Images

Fate brought Svitlana’s family together with other refugees in Odessa, fleeing the war in the East. Together, these IDP families rented out the second floor of a private house in the suburbs of the city, and lived there for a little less than a year. The children quickly took to the nearby school and kindergarten. The daughters of the families living together went to the same grade. When one of the girl’s classmates learned about their situation, they began to gather clothes and sheets, dishes, and other necessities of life for the family, Svitlana recalls tearily. But there were a few troublesome situations.

“Once, I had a very uncomfortable conversation with one of the educators at the kindergarten, where we sent Yukhym. She once told the five-year-old boy that ‘if something like this happened here [in Odessa], then we would have without hesitation let Russia in, and there would have been no war.’ For me, this is a completely unacceptable thing to say, especially to children,” says the woman.

Svitlana Tarakhkalo

It was also difficult to find work. Employers, one after another, refused to hire IDPs, saying that they were here one day, gone the next. ‘Why should we take you, if you’ll just go back home in three months?’

Later, after months of searching, Svitlana’s husband was offered a job in Chernivtsi, or Ivano-Frankivsk – their choice. The couple chose the second option. It was scary to move again, as neither Svitlana nor her husband had ever been to Ivano-Frankivsk.

Ivano-Frankivsk’s train station. Photo: Yurii Rulchuk / Ukrinform / Barcroft Media via Getty Images

In this new city, Svitlana recalls, she was impressed and taken in by people’s attitudes. This family of IDPs was respectfully accepted by the community.

“When we were looking for housing, I immediately told the realtor that we were migrants. And then he asked, ‘What, does that mean you’re not people?’ I replied that we also have three children, because in Odessa that regularly rejected us from renting. The realtor was surprised that I mentioned this, because Ivano-Frankivsk has a lot of multi-child families and this doesn’t raise any questions,” she explains.

Local NGOs helped Svitlana’s family meet others who were also forced to resettle from the occupied territories. This seemed to help integrate the family into their new community – they would meet, share their problems, and chat often. These NGOs held many different events for the IDP cohorts in Ivano-Frankivsk – and one of the organizers of these events was the NGO ‘STAN’.

Positive and negative peace

Once the discussion had fully ignited around the table, it became clear that most of the participants understood peace as the lack of war. For Ukrainians, peace was mostly when the shooting stops and the occupied territories are returned. As Yuliya Lyubich explains, this understanding is called a ‘negative peace.’

In 1969, Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung proposed two ideas that influenced the development of world psychology. These ideas indicate a difference between positive and negative peace. Negative peace means a lack of war and other forms of direct violence, while positive peace implies conditions in which various social factors eliminate the causes of violence.

That is, in the first case (positive peace), we aim to fight against already existing violence (in our case, the war in eastern Ukraine). In the second, we look at not violence itself, but its causes. This is when governments don’t strengthen punishments for, say, theft, but do everything possible to reduce the reasons for theft. For example, they try to create new, well–paid jobs or conduct some reforms that raise the citizenry’s quality of life.

The International Day of Peace 2021 in the town of Slovyansk. Photo provided by NGO ‘STAN’

“That is, in the case of a negative peace, people see peace as the solution to some concrete problems, while we try to engage people in the concept of positive peace. And this is a much broader concept than just the end of the war. This is about safety in society, and about the equality of every person regardless of their identity, and about neighborliness and mutual respect,” Lyubich tells us.

The “Events for the International Day of Peace” project is set at building, specifically, a positive peace. And this contains questions such as the lack of effective reintegration policies for veterans, the stigmatization of national and regional minorities, hatred towards the LGBT community, and the continuing dehumanization of those people left in the occupied territories.

Reintegration

Yuliya Lyubich says that she keeps track of how very different people discuss the same topic, it’s incredibly interesting to her. For example, one of the topics suggested for discussion at these events was the reintegration of people who were forced to remain in the occupied territories. In the small town of Zastavna, in Chernivtsi region, this question brought the participants into a certain stupor.

The International Day of Peace 2021 in the town of Zastavna. Photo provided by NGO ‘STAN’

“First, people say: ‘We’re far away from this, it doesn’t matter to us.’ Then they begin to think about it, and someone says that ‘if they wanted to leave, they could, so there’s no need to reintegrate them.’ And then someone imagines themselves in that same situation and insists that ‘I also wouldn’t leave my home behind.’ That is, even in one community people can have a variety of different points of view, regardless of the fact that the problems of the occupied territories in general have no influence on their daily lives. At the same time in Zaporizhzhia, which is territorially closer to the occupied regions, the participants were more involved with the topic and their discussions grew rather deep,” she told Zaborona.

The organization gathers and compares these ideas, and puts them into a global survey, which in the future could serve as a fundamental tool for lawmakers. This gathering also helps STAN understand where they should move forward in their projects, what concerns the population currently has and what initiatives need to be fleshed out.

“When completely different people with different points-of-view gather, you can find something new or spread some of your own ideas. You don’t exactly have to reach some sort of consensus, because everyone is different – and that’s normal. I’ve discovered many things that I had previously never considered during these events – for example, that the war doesn’t just result in losses, but in some skins of opening,” one of the participants of the “Open Dialogues about Peace”, Alisa Tenina, told us.

Svitlana Tarakhkalo was a facilitator at the discussions held in eastern Ukraine. In Zaporizhzhia, they discussed the issue of reintegration, and the participants had starkly contrasting thoughts on the matter. People seemed to have warm feelings towards the reintegration of IDPs and the question of peace, but from the other side, some said that in order to gain peace, Ukraine would need to obtain nuclear weapons once more.

“It was hardest in Lysychansk, probably because the language question there is very acute, and many consider this to be forced Ukrainization. They believe this to be unjustified and are waiting to be accepted the way they are, despite the fact that they still see the problem in Russian-language content and information they receive in that language. But somehow they aren’t ready to adjust yet,” Svitlana remembers.

The International Day of Peace 2021 in the town of Lysychansk. Photo provided by NGO ‘STAN’

It was sometimes rather painful for the woman to listen to people in Ukrainian towns. For example, in Melitopol, a few “Dialogue” participants stated that everyone who wanted to had left the occupied territories long ago, and everyone left stays due to their own volition.

“For me, peace is a state where you feel safe and have the ability to self-actualize. Even by our textbooks in school I can see that the most important thing is when a child can eat in peace, drink, express their needs, what they want, and excuse me, to just go to the bathroom. Then the child will be ready to calmly learn, to accept information. If this basic necessity of security isn’t guaranteed, then people will have trust issues, they’ll have problems having good-faith discussions or finding adequate resolutions. If you take a solution under some sort of pressure, then, probably, the solution will be completely different,” says Svitlana.

“It seems to me that the “Events for the International Day of Peace” is a way to raise awareness, to invite people to think about what needs to be done in order to have peace every day,” shares Yuliya Lyubich. “The question of peace is not a simple one. It sometimes seems that everything ic elar, but when you start going deeper, you begin to understand that the problem is much bigger than just letting some doves free or shooting off some fireworks. Peace is not something a priori given from nature. In order to preserve the peace, every person has to work for this every day.”

The International Day of Peace 2021 in the town of Bilovodsk. Photo provided by NGO ‘STAN’