Since the beginning of September, the Ukrainian military has liberated a number of settlements in the Kharkiv region. Currently, communications demining and repair are underway, and law enforcement officers are finding torture chambers and mass burials. Zaborona journalist Ganna Sokolova visited Balakliya and Izyum, spoke with the victims of Russian executioners about the occupation and electrocution, and attended the exhumation of killed civilians and soldiers.

“This is mine”

In the morning, people with bags gather on the platform of the Kharkiv railway station. It is dark outside: the sky is overcast. Passengers smile and discuss something animatedly. They are waiting for the train to Balakliya — the first train after the de-occupation of the city.

Balakliya, in the southeast of the Kharkiv region, was captured by the Russians at the beginning of the full-scale invasion. The city’s mayor, Ivan Stolbovy, voluntarily agreed to cooperate with the Russians, which is why the prosecutor’s office charged him of treason.

At the beginning of September, the Ukrainian military launched a counteroffensive in the Kharkiv region. The first liberated city was Balakliya. Sappers and utility workers immediately went there. And within a week, on September 15, railway workers restored the connection with Kharkiv.

-

Passengers in the train to Balakliya. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

In the electric train, seats near the windows are occupied by railway workers — they look at the track and traffic lights all the way, marking areas that need repair. Currently, the electric train consists of one carriage. It is only half full.

Some passengers go to intermediate stations that are not occupied. 70-year-old Maria Silchenko is on her way to the liberated Balakliya.

“That’s my home,” says the woman, smiling widely.

She lived in Balakliya until July when volunteers helped her to leave through the Pechenez dam — almost the only evacuation point from the occupied territories of Kharkiv and Luhansk regions. Maria lived in Slovakia for about a month.

“When people started to disappear, when they started to be killed… When houses started to be destroyed. [The Russian military] drive onto the bypass road, turn around and shoot at the city. And then they say: “These are yours, Ukrainians,” the woman recalls. “They entered apartments, houses, took everything out, loaded it into cars. They even broke the toilets! And what will people do? Nothing. Because they were with guns!”

Maria wipes her tears and smiles again.

The train arrives in Balakliya. Maria slowly steps onto the platform with two large bags. She looks around at the ravine’s puddles and the shrapnel-torn station building with broken windows. A woman walks onto a dirt road, hoping to catch a taxi.

-

The train station in Balakliya. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Maria Silchenko in Balakliya. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“Don’t say a taxi! Five bridges have been blown up,” wonders a resident who meets his wife from the train. “I didn’t believe until the last that the train would go.”

Passengers leave in their cars, with belongings, or go on foot. Someone chooses a short way through the forest — despite the mine danger.

Maria stays by the station alone. She looks at the empty road, where only cyclists ride. After a few minutes, the car stops — a resident has come to find out the train schedule. He agrees to take Maria home. He does not take money.

-

Balaklia. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“Survived,” the woman sighs with relief, looking at her high-rise building. There are still boards on which she sat during the shelling in the basement.

There is nothing to breathe in the apartment. Maria opens all the windows and checks the flowers — they have survived.

“It’s mine,” the woman says firmly.

It’s raining on the street, and the courtyards of high-rise buildings are empty. A boy suddenly looks out from the balcony. He offers coffee and, in a few minutes, comes down with the mugs.

-

Maria Silchenko in her apartment in Balakliya. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“I can also make you a coffee,” his neighbor, an elderly woman with disabilities, calls from her balcony.

She can’t leave the apartment but still joins the conversation. People here are thirsty for communication. She has to shout from her fifth floor.

“Civilians took refuge in the building”

A woman in a blue shawl walks past the entrance with her head down. Noticing strangers, she raises her eyes — they are wet with tears.

“I waited a month and a half for my son to be shot,” the woman says as if excusing herself for her tears and begins to cry even more.

It is Kateryna, the mother of local judge Volodymyr Strygunenko, who was persecuted by the Russian military while trying to persuade him to cooperate.

“You raised your son wrong!” These were the words Russians said when they met a woman on the street.

-

Kateryna Strygunenko. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

Kateryna introduces her son Volodymyr — the judge is in a tracksuit and a cap. And she, tired, goes home.

Before talking about the persecution, Strygunenko offers a tour of the court. We go to it through the city center, past destroyed buildings and lines for humanitarian aid. The court is only partially damaged. The inscription “Balakliya District Court of Kharkiv Region” and the state coat of arms were removed from the facade.

-

Balakliya after the occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Balakliya after the occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“Peaceful population took shelter in the building,” says the announcement still hanging on the door.

“Court cases are stored in the premises. Their destruction or interference will make the administration of justice difficult or impossible.” Papers with this text are on the door in several copies.

The judge wrote these announcements himself.

“In Russian, so that the occupiers understand,” explains Volodymyr Strygunenko.

-

Volodymyr Strygunenko near the Balakliya district court. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

In the first days of the war, the court worked normally. At the beginning of March, when the Russians tried to capture the city and shelled it, Strygunenko and his colleagues set up a shelter in the courthouse’s basement. They moved upholstered chairs and wooden benches from courtrooms. In total, about 70 locals were hiding in the basement.

When the Russians entered Balakliya, the shelter announcement did not help. They seized the building and drove people out of it. A sign was hung in the basement with the inscription: “Long live our court, the most humane court in the world!”

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

Volodymyr’s mother, Kateryna, catches up with us at the entrance to the basement.

“If my son is gone for a few minutes, I won’t find a place for myself,” the woman explains with a sad smile. “It’s a habit now.”

Inside there is a stench and a mess. Food, clothing, and ammunition are scattered everywhere. Volodymyr notices things from his office: seals, paintings, and even a toy bull in a mantle.

-

Volodymyr Strygunenko in the premises of the Balakliya district court. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Military equipment left by Russian soldiers in the premises of the Balakliya District Court. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“It’s a gift from the prosecutors,” laughs the judge.

“And here is already irrelevant news,” Strygunenko comments on the headline “In the vanguard of the battle for peace” in the newspaper “RosgVardiya Segodnya,” which was left by the occupiers.

Upstairs is also a mess. Every office and courtroom was robbed. Not a single glass cage was left for the arrested — the Russians transported them to torture chambers, which they set up in the buildings of the district police department and the printing office.

Russian flags, St. George ribbons, and propaganda newspapers are scattered everywhere. The windows are covered with stacks of papers stolen from the office. A bed in one of the offices is even made of folders with cases.

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

Among the papers on the floor, Strygunenko looks for his schedule to remember what he did before the war. The “Code of Conduct of the Russian Military in Battle” hangs on the wall nearby.

“Fight only with those who have weapons in their hands. Do not harm civilian objects,” the code reads.

“Yes, it’s about them,” Kateryna quips.

In one of the halls, rifles are seized from locals, weapons permits, personal files of court and ammunition warehouse employees, and passports of Ukrainian citizens — young men with local registration.

The Russians also left their documents here. One of them is called the “Book of records of washing of personnel in the bathhouse and changing of linen” and contains a list of the surnames of the Russian Guardsmen.

While walking around the court, Volodymyr comes across his belongings — a robe, shoes he wore to the meeting, furniture from his office, and even an icon. But the Ukrainian flag, hidden on the eve of the occupation, was never found by the judge.

“I had fresh blood stains under my feet. That’s how they set me up for a productive conversation.”

“I stayed at home. We waited for de-occupation, hoped for it,” says Volodymyr Strygunenko, as we sat down on dusty chairs in one of the courtrooms.

His mother recently underwent heart surgery, and his father has cancer. Both decided to stay in Balakliya. Volodymyr could not go: “What kind of son will I be after this.”

The worst started in June. Returning home, he noticed an unfamiliar car in the yard. I immediately understood that it was for him. He turned around and went to his parents to warn them. He returned to his apartment with his mother.

A few hours later, two Russian soldiers in balaclavas rang the doorbell. They told Strygunenko to take the documents and phone and drive with them to the district police station.

Before bringing the judge into the room, a bag was pulled over his head. It was filmed only in the office. Volodymyr was put on a chair. Opposite, four soldiers, or secret service members in masks, sat down.

“I had fresh blood stains under my feet. That’s how they set me up for a productive conversation, says Volodymyr. “The main task was to encourage cooperation. They offered to work in court with them. I refused, and said that I am a Ukrainian judge.”

Then Strygunenko was offered a job at the military commissariat. He refused again. Afterward, he was taken out of the district office building with a bag on his head and sent home.

-

Balakliya after de-occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

A few days later, a convoy of four cars stopped near the judge’s house. Five people knocked on the door. An employee of the FSB with the call sign “Irbis,” three Russian Guardsmen with the nicknames “Uragan,” “Atashka,” and “Berkut,” as well as a fighter of a private military company with the call sign “Gambit.”

They broke Volodymyr’s jaw – the asymmetry is still visible on his face. The man was taken to the apartment, put under the battery, and continued to be beaten. After that, he began to make claims.

“They were preparing for the arrival; they were informed about me, about our family property. They presented a claim that I did not want to cooperate with them. That my mother and I hid the man from ATO,” recalls Strygunenko.

His family helped a boy from the Shevchenkove village, who was kidnapped by Russians from his home and shot in the leg. He was kept in the torture chambers of Izyum and then in Balakliya. When the soldier was released, he could not go home to Shevchenkove due to the ban on leaving Balakliya, introduced for the May holidays. Strygunenko found the boy in the school’s basement, put him in a friend’s house, gave him clothes, and brought him food daily while the city was closed.

In addition, the Russians wanted to find out from Volodymyr the whereabouts of his entrepreneur friend, whom they had been looking for for a long time. The whole apartment was turned over. They found a supply of chocolate and began to eat it, washing it down with carbonated drinks.

They took the phone, passports, and keys. Some things, including coins from foreign trips, were packed in a suitcase. So, carrying this suitcase in front, the military took Volodymyr out of the apartment.

At the entrance, they came across his parents. The mother began to cry. They took Strygunenko to the plot where he was building a house for his parents and demanded that he rewrite it for them.

Ultimately, they took away the garden furniture and took the judge to the cultural center, the only place in Balakliya with a mobile connection. They ordered him to call a friend, an entrepreneur, and arrange a meeting with him. He understood everything and said to call back later.

The Russians were confused. They took Stryhunenko to the police and put him in a separate cell, where he stayed for about an hour. Then they took him to the cultural center again and forced him to call a friend, shooting over his head with a gun. The friend did not pick up the phone, so Volodymyr was taken to the police. His parents were already under the building.

“They actually fought me off, saved me. I could no longer be alive, or I would be a cripple,” Volodymyr sighs.

The Russians agreed to let him go but instead told him to come to the police the next day.

“I said I wouldn’t come. And if they want, they can come, like today, in a motorcade,” says Strygunenko. “They had such big eyes.”

Remembering these events, the judge endures long pauses and sighs heavily. However, he is talking about them for the fourth time. The first two times, the Russians forced him to tell about the abduction and beating on camera — supposedly for an internal investigation.

“There was a danger that we would simply be “wiped out.” That we will disappear,” recalls Volodymyr. “In our yard lives a woman to whom Russians came almost daily. And every time their car stopped here, we looked through the window to see who they were going to.”

For the third time, Strygunenko told his story after the liberation of Balakliya — to the State Bureau of Investigation employees, which checked all civil servants who remained in the city during the occupation.

The judge does not know what will happen to his job. But I am sure that the court building can be restored.

“We will live. That’s why we stayed alive,” Strygunenko shrugs.

His mother, Kateryna, invites him for lunch because no restaurant is open here. It starts to rain outside. People who stood in line for humanitarian aid are in a hurry to go home. There is a huge puddle under the entrance. Leaning over it, the neighbor scoops up rainwater with a metal mug and pours it into a bucket.

“She can use this water for the toilet,” Kateryna comments with understanding.

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

There is also no electricity in the city. In some areas, there is also gas. The mobile connection is still very weak.

The railwaymen, who came to Balakliya by the morning train, brought a generator and “Starlink.” People come to the station all day long to recharge their phones, call relatives and read the news. Nearby, those without a home are waiting for the evening train to Kharkiv.

“They either shooting or just playing”

“More than ten torture chambers have already been found in the liberated areas of Kharkiv region in various cities and villages. As the occupiers fled, they also dropped torture devices [torture instruments]. Even at the regular Kozachai Lopan railway station, they found a room for torture,” said President Volodymyr Zelensky. “Torture was a widespread practice in the occupied territory.”

In addition to Balakliya and Kozacha Lopan — villages north of the Kharkiv region — torture chambers were found in Izyum. It is a large city in the southeast of the Kharkiv region. The Russian army occupied it in April. In September, the Ukrainian military liberated the town.

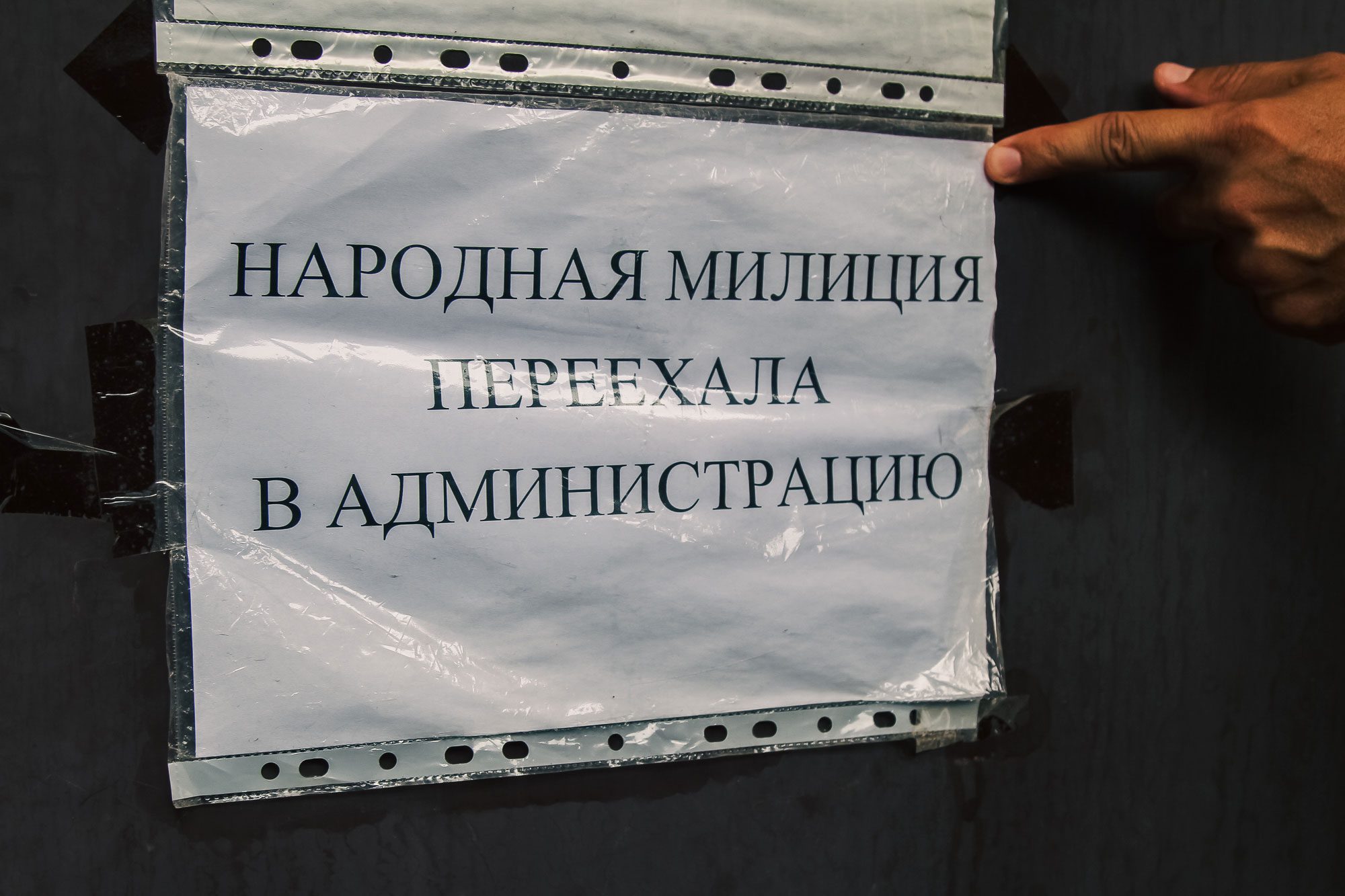

You can get to Izyum only by bypassing the blown-up bridges. On the Rostov highway are overturned and burned civilian cars, broken military equipment, and abandoned checkpoints marked with the letter Z. On the broken stop, there is the inscription “KPR” (Kharkiv People’s Republic.)

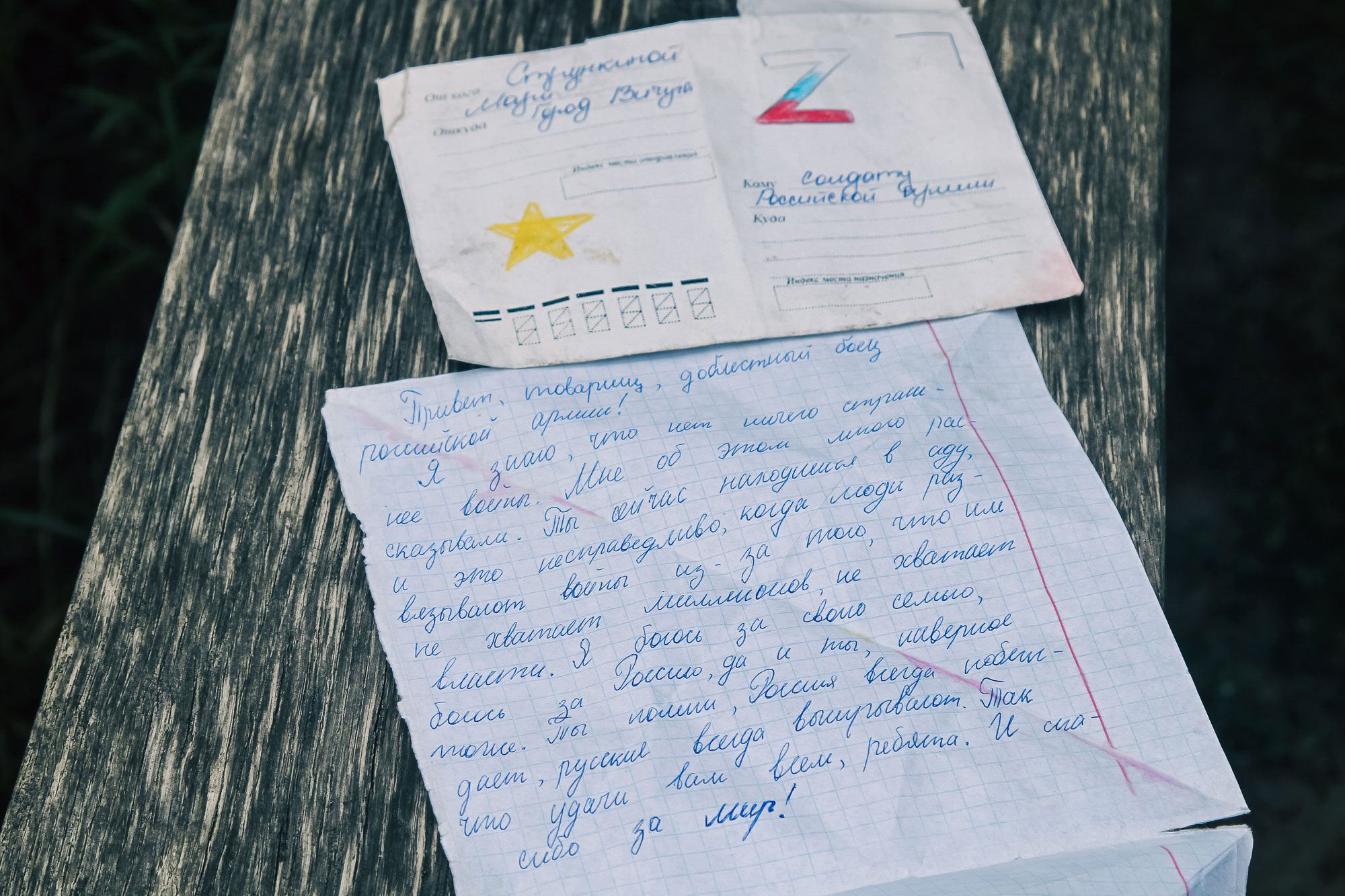

A dense pine forest grows on the outskirts of the city. Only one street runs along it. Serhiy, Lyudmila Chernyak, and their neighbor Nadiya Kalinchenko sit on a bench under the house with windows covered with plywood. They happily show their find — a letter to a Russian soldier.

-

Nadia Kalinichenko and Lyudmila Chernyak. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Serhii Chernyak. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“I am afraid for my family, and I am afraid for Russia. And you probably do too. Remember, Russia always wins; Russians always win. So good luck to you all, guys. And thank you for the peace!” wrote a girl from Russia to the soldier occupying Izyum.

-

A letter to a Russian soldier. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

The people of Izyum found this letter at the positions of the Russians, set up in a pine forest. They went there not out of curiosity but to take away the looted slate from them. It was needed to repair Nadia’s house, which was hit by a shell.

“They lived in houses, and they even removed the toilets. As they left, they took refrigerators and gas stoves. They came to us and said: “it’s empty.” And we hid everything ourselves a long time ago,” Ludmila laughs.

“And we removed the plasma,” joins Nadiya. “And they still say: “you live richly, you have both a refrigerator and a freezer.” One said: “I like Izyum, I will come here to live. Such a nice town, and a river. It will be the Belgorod region.” I said that we also lived well in the Kharkiv region.”

During the occupation, the Chernyaki spouses and Nadiya stayed at home. Bridges were blown up, and there was no communication. They ate their supplies and cooked on a campfire. Water was drawn from the spring, the only one on the entire street.

-

Serhiy Chernyak near his home. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“When the soldiers were standing here, we did not have the right to cross the road,” says Serhiy.

The sounds of gunshots could be heard from the forest from time to time.

“Either they shot someone, or they were just playing,” Nadiya shrugs.

From the windows of their houses, the residents of the street saw how two cars of the ritual service and the Russian military, with the markings “Z” and “Cargo 200” came to the forest every day. During the five months of occupation, a cemetery with 445 graves grew in the woods.

-

Cemetery in Izyum. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

As the French publishing house Le monde learned, the burial was handled by an employee of the local ritual service named Vitaly. He collected the bodies of civilians killed during the shelling around the city, and with the permission of the Russians, he buried them in the forest. A man placed a wooden cross on each grave, on which he wrote numbers. Under the first number lie those who died on March 3, under number 445 — those who died on September 15, already after the liberation of Izyum. Sometimes several people are buried under the same number. More often — one person. About 20 bodies have bullet wounds.

Vitaliy kept a notebook in which he deciphered the numbers — he indicated the data of the dead and the date of death if he knew them. The man gave this notebook to the investigators who came to exhume the mass burial on September 16.

After the de-occupation, official cars and refrigerator cars marked “Saltiv meat processing plant” were searched on the roadside. Dozens of specialists came here — police officers, prosecutors, special services, rescuers, forensic experts, and doctors. Leaning on shovels, men and women in blue robes waited for work to begin. For about an hour, sappers bypassed the territory. From time to time, you could hear the dull sounds of explosions.

-

Exhumation of bodies at the cemetery in Izyum. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

Meanwhile, Dmytro Lubinets, the Verkhovna Rada Commissioner for Human Rights, informed a crowd of journalists about the first body with signs of torture exhumed the day before.

“Hands tied behind the back with ropes. Most likely, he was tortured before that. And after that, they killed at close range,” Lubinets said. “We see that the local population’s intimidation system is the same. It is opening a torture chamber and a military commandant’s office, and this is mass torture, mass murder.”

-

Exhumation of bodies at the cemetery in Izyum. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

The next day, another body with traces of torture was found here — a man with his hands tied and his scrotum cut off.

“There are also whole families here,” continues Ombudsman Lubinets. “Father born in 1980, his wife born in 1991, their daughter born in 2016, and their parents. They are all lying next to each other. According to residents, they died due to an airstrike by a Russian plane when Russian troops were advancing on Izyum.”

The rescuers fence off the defined area of the forest with signal tape and let specialists through. Diggers pull crosses out of the sandy soil and begin work. A sharp cadaverous smell wafts into the air, cloyingly sweet.

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

Some tombstones have photographs in frames; wreaths hung on crosses. “Daughter from mother with sorrow” is written on a black mourning ribbon.

The diggers look focused. They remove mutilated bodies from shallow graves and pack them in plastic bags. Tired, they sit down on the sand. A tear glistens on the nose of one of the diggers.

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

The death of civilians will be investigated as a violation of the laws and customs of war, Oleksandr Filchakov, head of the Kharkiv Regional Prosecutor’s Office, said. The death of 17 Ukrainian soldiers buried in a separate grave is an encroachment on Ukraine’s territorial integrity and inviolability.

A medical examiner is working on the bodies of service members exhumed from mass graves.

“Layering of sandy soil,” he dictates to a colleague. “A corpse with a partial skeleton.”

The medical examiner removes the chevron from the deceased’s uniform and takes out soaked documents from his pocket. All this he carefully places in a plastic bag.

Nearby is another body in the uniform of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. A yellow-blue bracelet has been preserved on his arm, and a tattoo is visible on his chest. In a few days, on September 20, a resident of Nikopol will recognize her husband, Serhiy Sova, from the 93rd mechanized brigade “Kholodny Yar” by this tattoo.

-

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“I am asking you very much to facilitate the return of my dad home for a decent burial. I am very proud of him!” the son of the deceased will appeal to the Ministry of Defense.

Ombudsman Dmytro Lyubinets assumes that there are tortured prisoners among the dead soldiers. However, the exact cause of each of the deaths should be established by a forensic medical examination, Serhiy Bolvinov, head of the investigative department of the Kharkiv regional police, emphasizes.

As of September 21, the bodies of 320 civilians and 18 military personnel were exhumed. Some of the bodies have signs of torture.

“I endured for 15 minutes and then just blacked out”

“And will the journalists be taken to the Izyum torture chamber?” a man in a cap addresses Serhii Bolvinov, the head of the investigative department of the Kharkiv regional police, during a press conference.

It is Maksym Maksymov, a resident of Izyum, publicist, and contributor to Ukrainian publications. He spent time in the torture chamber in the district police department from the beginning of September until the city’s liberation. The man was arrested by Russians who introduced themselves as military police.

-

Maxim Maximov. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

“When we got home, they put me against the wall,” recalls Maksym. “We were already trained. You listen to any noise. In general, you had to listen very carefully here. To hear in time when a mine is flying and when a car is approaching.”

The Russians conducted a search and took the man to the district police station, putting a bag on his head. Maxim was kept there in the basement. Together with him, there were two people from ATO, Serhiy, and Oleksiy.

“Political ones are in the basement. Criminals are on the first floor,” he explains.

They did not explain the reason for the detention. They took us for questioning only the following day. Maxim was put on a chair; his hands and feet were handcuffed, and electric wires were connected to them.

“It is extreme pain. You start to spin. You are trying to free yourself somehow,” Maksym shows the wounds from the handcuffs left on his wrists and ankles. “I asked my cellmates how long I was gone. They said 40 minutes. I think I kept going for 15 minutes, and then I just blacked out.”

“They didn’t even ask questions,” the man continues. “They were just electrocuted. They said to all my questions about what they need: “You know everything, say it yourself.” He didn’t say anything until he blacked out.”

The torture was repeated the next day. Only on the third day the Russians began to ask Maksym questions: when and where the Security Service of Ukraine recruited him.

“As evidence, I was presented with maps of the Donetsk and Kharkiv regions. These are ordinary paper maps, folding. And they told me I was correcting the fire,” says Maksym.

-

Trophy Russian tank in Izyum. Photo: Ganna Sokolova /Zaborona -

The destroyed building in Izyum. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

The Russians also asked him about other residents of Izyum — who used to serve in the ATO, who are now in the Teroborona, or who have pro-Ukrainian views. The man is convinced that Russian special services carried out the torture, and the so-called “law enforcement officers” from Luhansk were based in the district department.

“The evening before the counteroffensive, they were very nervous. A man from LPR came and said: “The army is advancing. Suddenly, we’ll just throw a grenade into every window,” recalls Maksym. “In the morning, they heard a noise. The man came running, already in civilian clothes, because they were running away. They opened all the cameras, told them to take their documents and run.”

When he went upstairs, the man saw several hundred passports of local residents scattered around the room. The next day, when Izyum had already been released, Maksym came to the district office to see the torture room. He found all the tools there – handcuffs, sticks and a telephone device that produced electricity.

-

Izyum after the occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Izyum after the occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

-

Izyum after the occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona -

Izyum after the occupation. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

Maxim remains in Izyum and plans to write a book about the experience of life in the occupation.

“There is a lot of information in these six months. I am a psychologist by education, and it was interesting to observe how people changed – some for the better and some on the contrary. How was Stockholm syndrome expressed,” he muses.

“You told someone that you are not afraid of us”

As early as September 16, President Volodymyr Zelenskyi announced that almost all of the Kharkiv region was de-occupied. Before the counteroffensive, the Russians occupied 32% of the territory of the Kharkiv region, now only 6%, said the head of the Kharkiv regional administration, Oleg Sinegubov.

The Russian army retreated and began to strike at critical infrastructure. On September 11, Kharkiv and part of the region were left without electricity and mobile communications. The city emptied even more. At the same time, local volunteers became active. They carry drinking water, food, and medicine daily to the liberated towns and villages.

The Russians are shelling the de-occupied territories, particularly the Kupyan district in the region’s east. On September 20, two people died there, and nine others were injured. So the volunteers are evacuating the local population.

The Kharkiv railway station is crowded again. Those who survived half a year of occupation and a week of massive shelling are waiting for the Kyiv train. These are primarily residents of Kupyansk.

Lyudmila, an older woman, is standing in the station hall next to a pile of bags. She looks tired but has nowhere to sit. A woman hides a frightened kitten in a wide-knitted sweater.

“They threw it away,” says Lyudmila. “And where are his children when there’s a war?”

During the occupation, Lyudmila lost 12 kilograms of weight.

“There were more or less Russian soldiers by themselves,” the woman recalls. “But LPR and DPR are complete darkness, and they are bastards! What they didn’t do: take people’s cars, arrest them, and beat them…”

The Russians also detained her son Oleksandr. He asks not to specify their surnames because his sister lives on the occupied outskirts of Kupyansk. There is no connection with her.

-

Balakliya was released. Photo: Ganna Sokolova / Zaborona

At the beginning of the occupation, Oleksandr took part in pro-Ukrainian rallies. And in a few months, the Russian military came to him.

“I opened the door, and they asked: “Is your name Sasha?” They pulled me into the entrance, and the three started beating me. I ask: “For what?” They: “You told someone that you are not afraid of us,” says the man.

He was taken to the district police station but was soon released home. Oleksandr was assigned ten days of “training” — he had to come to the district office and perform household chores, from painting walls to chopping firewood.

“I couldn’t say no. They said they would find me and execute me,” Oleksandr explains.

He heard how the prisoners kept in the cell sang the Russian national anthem every night.

“They intimidated the city so much… I’ve never seen Kupyansk like that,” the man sighs. “When our army entered the city, our whole family stood by the window. We had tears in our eyes. That’s all, that’s all!”

Even now, the man is barely holding back tears.

“Sorry, I’m exhausted,” he says, returning to his bags.

The material was created within the framework of the “Life of War” project with the support of the Laboratory of Public Interest Journalism and the Institute for Human Science, Vienna.