“I Was Always Called the Same Thing — a Cow or a Pig”.

What It’s Like to Have an Eating Disorder in Ukraine — and Why These Disorders Are So Dangerous

Author: Yuliana Skibitska

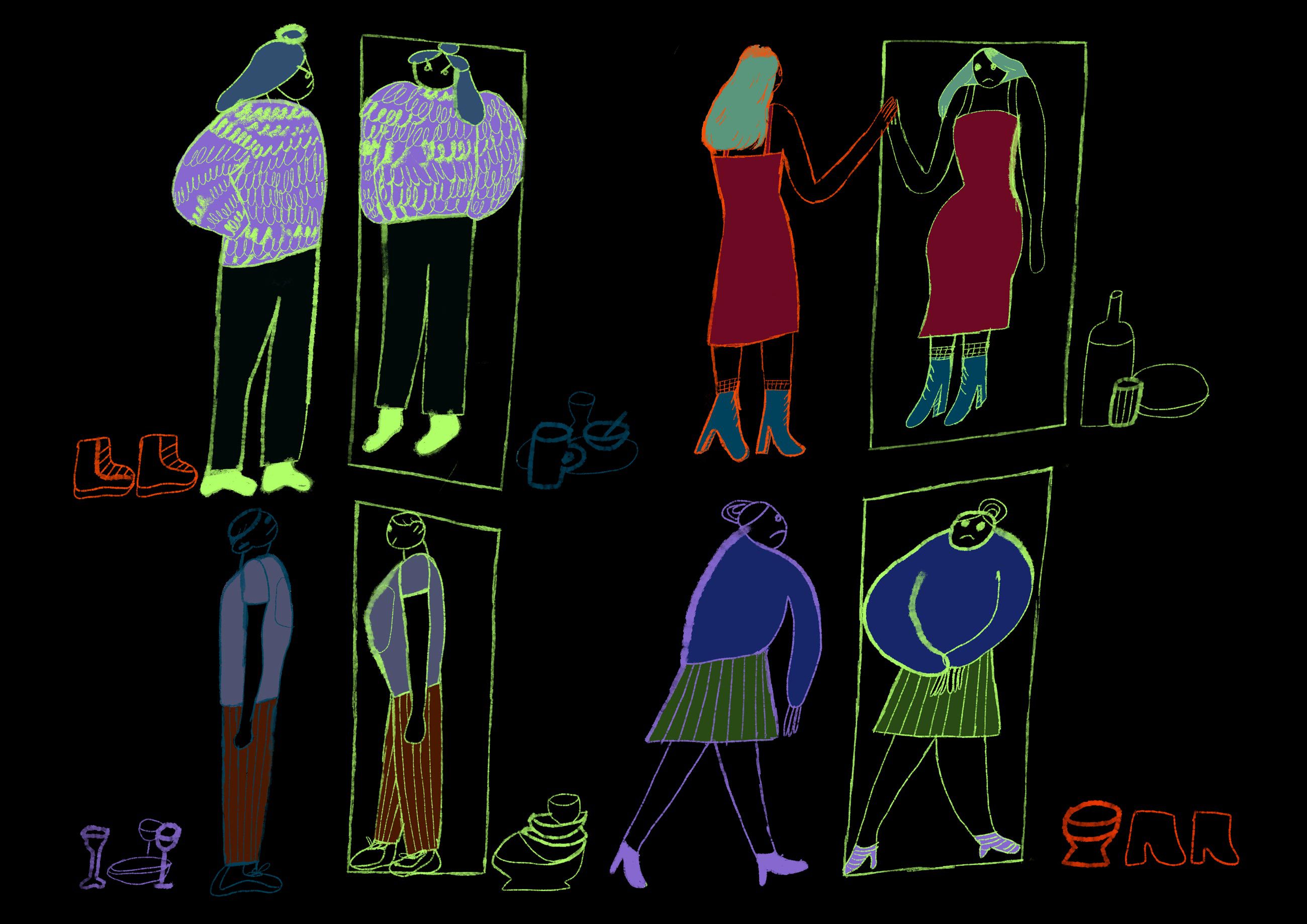

Illustrations: my_pet_spider

At least 9% of people suffer from eating disorders (EDs). This figure is not exact because many countries lack statistics on EDs, but according to experts, it is highly likely that the number of people living with EDs has increased as a result of COVID-19. The International Classification of Diseases characterizes eating disorders as mental disorders. One person dies from an eating disorder every hour. Anorexia nervosa, known simply as anorexia, has the highest mortality rate of any eating disorder. Nevertheless, many people are unaware that they have problems with their eating behaviors, and the longer a person lives with an eating disorder, the more difficult it can become to treat their disorder. After speaking with several people who suffer from various eating disorders, Zaborona’s Deputy Editor-in-Chief Yuliana Skibitskaya reports on the origin of EDs, why they’re so dangerous, and how to address them.

This article contains descriptions of bullying, domestic violence and physiological processes.

Eighteen-year-old Anya (whose name has been changed at her request) is on the way home from school. She’s in a hurry — she was to make it to the store before the workers go on break. She gets the same things she gets every day: Flint (a popular Ukrainian snack brand), Coca-Cola, ice cream, and a Korona chocolate bar with nuts.

Anya is now 30 years old. She comes into the store and buys the same combination of snacks she’s been buying for years, only now the portions have become much larger. In some stores, the workers have started recognizing Anya: “Will you be having the same as always?” they ask. When this happens, she replies, “yes, same as always,” then stops going to that store altogether.

Anya now weighs around 120 kilograms (264 lbs) and is 164 centimeters (6’4) tall. In the past, she’s weighed even more — at one point, she weighed 166 kilograms. “Can you imagine how it feels when your weight is the same as your height?” she asked Zaborona. “Eventually I realized I just couldn’t walk.”

I’m speaking with Anya by phone. I don’t know how she looks now —her Facebook account only shows old photographs from when she weighed less. In her profile picture, she looks like a pretty young girl. Anya has sent me photos from when she experienced her greatest weight loss — they show her fitting both of her legs into one leg of a pair of jeans. The next photo shows her on a scale that reads “166 kilograms” (366 lbs). Her face is not visible.

“I’ve lost and gained weight so many times I could already write a book about it,” said Anya. People in the gym might say, “Hey, have you tried drinking only kefir and gorging yourself on raw buckwheat and pieces of dirt?” “No, you know, I haven’t tried it.” Now, when they say these kinds of things to me, I just want to body slam them. I’m like a raw nerve.”

Little parties

Anya grew up in a small town in Chernihiv Oblast. At first glance, her family is pretty well-off: her father is a wealthy businessman by town standards, her mother is a housewife, and she has a younger sister. But her relationship with her parents has been fraught since childhood.

“From a young age, Mom always beat me,” said Anya. “Once, when I was eight years old, she broke my arm. I think this was because I came into my parents’ bedroom at, let’s say, an inappropriate moment. I always had only one name — ‘fat cow,’ or ‘swine.’ I remember how, when I was small, I would often sit and comb my hair for hours, ripping out tufts of hair. I was quieting myself.”

Anya’s father, in her words, took a passive position and didn’t interfere in the relationship between mother and daughter. Anya’s parents later got divorced, and her father completely dropped out of Anya’s life. When Anya was 15 years old, her mother kicked her out of the house. She went to live with her grandmother, where she was repeatedly told how “fat” she was.

Food, Anya recalls, was always her only comfort. She was at her happiest when she stayed home alone. Then, in her words, she would throw “little parties” — she would pour out the sweets and chocolate bars she had bought on the couch, and eat them along with Coca-Cola. She could put down 5 to 6 liters of Coke in a day. Anya hid the bottles in the closet, then snuck them out of the house and threw them into different garbage cans. This habit continued until Anya was 27 years old.

Naturally, Anya was teased and bullied at school.

“Now they call it bullying, but then it looked like this: you are fat, and your classmates and students in two parallel classes laugh at you,” Anya told Zaborona. “You know, in every class there’s someone who gets pushed around the most, whom students constantly spit at from behind. They didn’t spit at me, but they sent me [offensive] text messages, they called me on the phone — it’s good that there was no Internet back then.”

Anya would pay her sister to go with her to take out the trash because the dumpster was in the courtyard where her classmates lived. When Anya’s sister said she was ashamed to walk down the street with her, Anya started to throw trash into her family’s basement — her parents would get mad that “those assholes and drunks had fucked everything up” down there.

When she was in the eleventh grade, Anya decided to lose weight. She lost 15 kilograms (33 lbs), but according to her, this “didn’t count.” Her most successful attempt to lose weight was at the age of 22, when she managed to lose 40 kilograms (88 lbs) from an initial weight of 120 kg (265 lbs). This was not healthy weight loss – Anya continued to eat unhealthy foods and drink her beloved Coca-Cola, but she worked out often and tried to maintain a calorie deficit.

“And all was well — I just had 10 kilograms (22 lbs) left to lose and it would have been great,” Anya said. “But I ended up in the hospital, and they removed my gallbladder. When they discharged me, the doctor told me to forget about sports. Eventually, the kilograms not only came back, but I actually gained more weight.”

Two fingers in the mouth

According to the latest data, at least 3.5 percent of the population suffers from binge eating disorders. Women are more at risk — 2 percent of them struggle with binge eating at least once in life. Binge eating disorders are when people experience fits of behavior during which they can’t control the quantity they eat because they don’t feel full. In one type of this disorder, pica, people consume non-nutritive, largely inedible substances.

“These disorders are connected, among other things, to psychological trauma in personal attachment that an individual has experienced at quite a young age. That is, something happened to one of their close relatives who was supposed to be close to them and care for them,” explained Anna Gerasimenko, a psychotherapist who treats EDs. “Such people, generally, have difficulty feeling basic feelings of security because babies are also emotionally attached to the adults who nurture them. Food can become one of the means for satisfying one’s needs, to please oneself, and to calm down.”

Binge eating disorders (BED) often lead to bulimia, which is when a person forces themselves to throw up after a fit of BED. Bulimia is also more widespread among women, for whom it is 10 times more common than among men. The symptoms of bulimia include a strong concern about one’s weight and regular restrictive diets, which are almost always followed by breakdowns, or binge eating. People with bulimia often use pharmaceutical substances — for example, laxatives or diuretics. This leads to problems in individuals’ gastric tracts and kidneys.

Sasha is 23 years old. At the age of 12, a medical examination revealed a problem with his thyroid — it appeared he was overweight. Sasha desperately wanted to lose weight, but was unable due to a hormonal problem. That’s when Sasha first used the “two finger” method. “Objectively speaking, I was overweight,” Sasha said. “The doctors said that I needed to lose weight, my parents [said this as well], my classmates mocked me. My parents signed me up for swimming, but this didn’t help.”

Although he was born and grew up in Ukraine, Sasha is ethnically Tajik. When he gained weight, his classmates teased him. They called him “fat,” “Chinese,” and a “homo.”

“I developed a complex, because I’m non-Slavic by appearance, in addition to being fat. My parents’ adult friends said that they needed to treat their boy, because he will have ‘mirror sickness [a popular insult for men, as the saying goes, who can only see their sexual organs in the mirror due to having a large stomach],’” Sasha said. “I didn’t understand what they meant.”

Sasha wanted to lose weight, but he couldn’t resist food. According to him, he could eat a full pack of pasta without noticing. Vomiting after each eating session began to seem like the only solution. He liked the feeling of ease and euphoria that would arise after vomiting. But according to Sasha, the vomiting technique has its difficulties. The first time you try it, he explained, attempting to get rid of all the food definitely won’t work. Inducing vomit subsequently becomes more complicated because the mouth’s receptors adapt.

At 17, Sasha developed a new addiction: drugs. Usually, he took uppers or amphetamines. Because of his new habit, Sasha’s food addition took a back seat. He also lost a lot of weight due to the drug use.

“I was already eating less and less often,” he said, “but still, there were times when I was routinely overeating (binging) once a week. Usually it was on a weekend. I would stuff myself full, and then I would go to barf.”

Esoterics

Modern scholarship divides the possible causes of eating disorders into several categories: genetic, social, and psychological. Anorexia, for example, can be a hereditary disease in nearly half of cases. Social causes refer to a person’s relationship to society, while psychological causes refer to a person’s particular psyche and temperament.

This is a highly simplified framework. EDs are often a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder, and can occur simultaneously with other mental disorders such as anxiety disorders, clinical depression, and borderline personality disorder. According to Anna Gerasimenko, it’s rarely possible to pinpoint a single cause for EDs; there’s usually a combination of interconnected causes.

Twenty-seven-year-old Alica Volkova now understands that the first signs of her unhealthy relationship with food appeared in her childhood.

“I was constantly overeating as a guest in others’ company,” she recalled. “After all, it was the hungry nineties — you would go over to someone’s house, and everything would look so nice and delicious. And mayonnaise-y. Then, at home, my family would say to me, ‘How are you not ashamed? What, are you from a hunger-stricken region?’ And this gave me anxiety, but nevertheless, I continued to overeat.”

Alisa Volkova at the peak of her anorexia

According to Alisa, adults often don’t give much thought to what they tell children. For example, while she never encountered harsh bullying from peers, adults would still say “what a big ass you have,” or “ugh, what cheeks you have.” Ostensibly harmless words could hurt Alisa deeply. Moreover, she grew up during a time when it was especially fashionable to be “skinny.”

“Sometime when I was in the eighth or ninth grade, this trend of all these various esoteric practices appeared — the less you ate, the more spirituality you had,” Alisa recalled. “As if you get energy not from food and carnal pleasures [but from somewhere else]. This idea appeared that sugar is the main evil, that all of it is part of an unhealthy lifestyle. I got addicted to it.” Depression compounded the unhealthy propaganda. In the eleventh grade, Alisa started her first diet and liked it. The diet was effective, and Alisa soon weighed around 50 kilograms (110 lbs) while standing 169 centimeters tall (5’6); in other words, she was underweight. Nonetheless, she would look at herself in the mirror and think about how fat she was.

Anorexia as a trend

In the 1960s, a British woman named Leslie Hornby became the face of celebrity hairdresser Leonard’s London salon. He even came up with a pseudonym for her, “Twiggie,” a reference to her weight. Leslie was indeed very thin – she weighed 41 kilograms (90 lbs) and was 166 centimeters (5’5) tall.

Twiggie quickly became a fashion icon, replacing Marilyn Monroe as the ideal of adolescent thinness. Millions of girls across the globe lost weight in attempts to resemble Twiggie.

“The trend went from having a figure the size of Monroe’s to one like Twiggie’s in 20 years – this is a very brief period of time and too radical a change,” said Anna Gerasimenko. “And if a 20-year-old healthy woman could have a figure like Monroe’s, she wouldn’t be able to have one like Twiggie’s at 40. Fashionable body forms, which are generally presented to us by the mass market, are unattainable 80% of the time for the average woman without extreme effort or surgery.”

The skinniness trend took hold and spread around the world. The openness of the Internet gave rise to online forums where teenage girls would discuss how to lose weight. This discourse later moved over to public forums on “VKontakte” (note: a social network like Facebook popular in some post-Soviet countries) — almost all of them were named “Typical Anorexic.” These groups still exist — their membership ranges from 20 thousand to 200 thousand users. An entire community has formed around a common interest; girls meet each other online, share ideas for extreme diets (600-800 calories a day), and seek out weight-loss partners.

Since TikTok began to rival “VKontakte”, the theme of EDs has become popular there as well. Videos of teenagers carrying out their personalized ED schedules are common — users show their daily rations of 400-600 calories and share their frustrations or breakdowns.

@powerpuffleya 450 ккал. #дневникпитания #калории #дефицит #рпппусалочка #рпппчек #рпппвсим #рппп #дневник #пп #еда #fatsecret #ккал #ed #подсчетккал #анобабочка

♬ оригинальный звук – Tik Toker

On the other hand, however, there’s content promoting the idea of having a healthy relationship with one’s own body. The creators of this kind of content address people using unhealthy means to become thin and encourage them to love themselves flaws and all.

@sakikijj Не надо так 🙄 #ропэпэ #рппчек #подсчеткалорий FW ⚠️

♬ оригинальный звук – Мазута 🦈

Twenty-three-year-old Oksana has been dieting since she was 15 years old. She told Meduza that because she was a large baby, she looked older than many of her peers.

“When I was a kid, boys would tell me I was fat,” Oksana said. “Although I wasn’t fat, I wasn’t skinny, either. I learned to defend myself from these attacks, but when you’re only 13, you see everyone around you falling in love, or developing some affection for boys. I began to think about losing weight. I thought to myself, ‘alright, I’ll slim down and by New Year’s I’ll fit into a beautiful dress.”

According to Alisa and Oksana the fashion industry was one of the driving factors in their desire to become skinnier.

“You’re watching TV, and everyone there has a perfect figure and looks beautiful,” said Oksana. “You read fashion magazines, and everyone there is beautiful as a result of being anorexic and skinny. You look at yourself, and you don’t look like that, and that means you’re not beautiful.”

Oksana severely limited her food intake for a year, saw her weight drop to 45 kilograms, and at 16 ended up in hospital with gastric erosion. Her body had stopped tolerating food, and before that she had stopped menstruating. There were many other girls in the pediatric gastroenterology clinic with the same condition.

“There was a girl who came to stay in that hospital every year. She was a model — all of the janitors, nurses, and doctors knew her, because each year she would come back. Some of the girls there probably couldn’t even drink and just looked like live skeletons.”

The gastroenterology clinic was located in Kyiv on what used to be called Frunze Street (now Kirillovskaya) across from Pavlov Psychiatric Hospital, where psychologists in the gastroenterology clinic would send children who refused to speak to them. In the psychiatric hospital, Oksana recalls, the psychologist would ask why she considered herself “fat.” None on the girls there could answer that question.

“At some point, you just start thinking everyone around you is thin and you’re fat,” said Oksana. “And that’s it. At the same time, on ‘VKontakte’ there are a million different things that help you slim down, go on a diet, start exercising, and a bunch of stuff like that.”

Alisa started taking weight loss seriously in her third year of university, when she saw her weight, 53 kilograms (117 lbs), on the scale. Despite this actually being a low weight for someone of her height, Alisa thought, “This is horrible, this is hell.” She sharply decreased her food intake and started intensive physical training. Sometimes she would break down and overeat, vomit to get rid of the food she had eaten, then continue with her weight loss diet.

“Then there was New Year’s Eve with friends. I spent the night assuring them, “everything’s fine, I’m just sitting in the bathroom.” And it didn’t matter that I was coming out of the bathroom in tears, with bite marks on my arms. There were so many mayonnaise-laden salads because it was a New Year’s Eve celebration, and this, of course, put me over the edge.”

Alisa continued working toward her degree and worrying, unable to sleep or eat. She was depressed, and everything was “fucking awful,” in her words. She weighed 43 kilograms (117 lbs), and she had already stopped menstruating. Over the next two years, she continued to lose weight until she only weighed 35 kilograms (77 lbs).

The path to recovery

Experts consider anorexia one of the most dangerous EDs. At nearly 30%, it has one of the highest mortality rates of all psychological disorders. The risk group for anorexia, as for other EDs, consists primarily of teenagers, but, as Anna Gerasimenko adds, eating behavior disorders can emerge at any age beginning at about 5-7 years old.

“We talk about teenagers [as a risk group] because at that age, all of the organs are completing their development” Gerasimenko explained. “Hormonal disruption in girls leads to the disruption of the menstrual cycle, which, in turn, leads to problems with conceiving children. Similarly, in boys, puberty disruption and growth retardation are possible. If anorexia lasts two years or longer, girls’ bones will be brittle, with lowered calcium content, similar to what women experience during menopause. Restoring [the normal level of calcium] is quite complicated and often impossible.”

Alisa once woke up and saw so many hairs on her pillow that “you could have made a wig out of them.”

“I realized that I needed to either go request a space at the cemetery or change something,” Alisa said. “I did my last photoshoot at 35 kilograms and started to work on myself.”

Alisa read books about recovering from EDs, and found forums and chat rooms on “VKontakte,” where people with these same problems interacted with one another. Gradually, she began to gain weight. She recalled a time when she travelled with a friend to Istanbul, walked around, ate Turkish delights, and felt happy. Recovery, however, was complicated.

“My acquaintances and friends who had become used to my extreme thinness would say to me, ‘Oh, your cheeks have finally appeared,” said Alisa. “But you react really nervously to such remarks. Sometimes I wanted pizza and asked friends to go to the café with me, because if I went alone, I just couldn’t bring myself to order it.”

Recovery from EDs is a long process that depends on a number of factors. According to modern protocols, it takes one to three years. The speed of recovery depends on the age of the patient, the duration of their ED, and the severity of their condition. Treating EDs requires a multilevel approach, including a psychotherapist who helps establish a healthy relationship with food. In the therapy process, breakdowns and relapses are unavoidable, and it’s important to convey to the patient that this is normal, said Anna Gerasimenko. In these cases, the nutritionist reviews the patient’s therapy plan and, possibly, will correct their eating plan.

“The first thing we work on is regulating the patient’s emotional state,” said Anna Gerasimenko. “Then, the patient requires the help of a nutritionist who balances how the patient feeds themselves. This is not a strict diet, but a structure that helps the client avoid overeating while eating a sufficient quantity of food. Using this process enables the patient to reduce their anxiety and shed or gain weight following anorexia. It is also important for the patient to ask their friends for help. For bulimia patients, it’s important for friends to tell them that they’re not well, that it’s not good to go out, eat a lot of food, and then vomit it out. The patient needs to ask someone close to them to be with them so that they don’t resort to bulimia.”

Experts diagnosed Sasha with anxiety, borderline personality disorder, and bipolar disorder. He used drugs actively for around five years, but has since stopped and recovered. Sasha tries to look after his health and eating. But all the same, he said, sometimes he relapses and again feels the sensation of euphoria after vomiting. Nonetheless, he said such relapses happen less and less often: “I’m convinced that sports and physical activity really do suppress your addiction and make you more resilient.”

Following her hospital stay at age 16, Oksana continued to diet periodically and shrunk to 40 kilograms. Then she began seeing a psychotherapist and unpacking the trauma that had led to her anorexia. Now, she said, she still harbors the damage of jokes made at her expense, calling herself fat, but she has no desire to restrict her diet to water. “You start to realize you need to draw strength from somewhere in order to live, somehow. Plus the people close to you support you — they say that everything is okay [with your weight], don’t overthink it.”

According to Alisa, when she started to recover from anorexia, she started to realize that the disorder affects more than just food. “It is becoming clear that to say, ‘guys, I’m hungry, stop the car, please, let’s go into the station and I’ll buy myself food,’ that’s not about food, but about being either comfortable or uncomfortable. I resolved a lot of things while working on myself.”

Alisa’s weight is now healthy and she feels well. She had relapses during her recovery, but now she’s kept her ED in remission for a long time, she eats normally, and she exercises. At the same time, she often visits the dentist — the anorexia severely affected the quality of her teeth, and she had to have crowns installed.

Anya hasn’t been able to resolve her problem so far. She says that she often does not want to go out into public because of her heavy weight. Bullying has not stopped in adulthood: “One time, a man who walking across the street shouted at me, for everyone to hear, ‘Hey, you, pig!’”

Anya understands that she needs the help of a medical professional, but she’s unable to go to a psychotherapist — she can’t afford it. “I used to think that if I lost weight, all of my problems will go away. Now I don’t even believe in this.”

Signs of eating disorders, according to Anna Gerasimenko

- You frequently or always use food to regulate your emotional state. Food is becoming your main source of pleasure and a way to cope with stress or forget about your problems.

- The process of consuming food causes you to become tense and fearful. You are afraid to eat certain food products, and you experience shame and feelings of guilt after eating.

- You force yourself to vomit after eating.

- You are highly concerned about the condition of your body and are unsatisfied with it. Losing weight, even one kilogram, seems like it can resolve all of your problems and make you happy.

- You cannot control the process of consuming food and you regularly overeat.

Translated by George O’Hara from Respond Crisis Translation