What did the life of a Soviet soldier look like? He was constantly moving from place to place, dragging his family with him, changing countries of residence and trying to keep in touch with the places of his childhood. Zaborona’s photo editor Pavlo Bishko regularly explores the archives of amateur photographers who recorded life around them decades ago. Earlier, he, for example, found the archive of Mykhailo Kosyuk, who photographed the Transcarpathian village of Ust-Chorna, the ancestors of Austro-Hungarian loggers and the forests and mountains shrouded in foreign currents.

And recently Pavlo met Volodymyr Travnikov, a Lviv builder who created a museum of abandoned things in his basement. There he collects discarded things that have served their purpose (read the article here). Travnikov shared the photo films of Soviet soldier Rufim Shkolnikov, who documented his entire life with a photo camera. In total, the archive includes more than 5 000 photos taken from 1956 to 1999.

Zaborona publishes a selection of the most interesting photos that demonstrate the typical path of a military family from Soviet times to the beginning of Ukraine’s independence.

Rufim Shkolnikov was born in 1930 in the village of Sobakino, Penza region of Russia, served in the Soviet army in Kamchatka, and at the age of 26, he began to take photos of his life. First of all, the military photographed his wife Oleksandra and sons Ihor and Dmytro. Among the photos preserved in Shkolnikov’s archive, there are visits to the family in the Tula region, vacations in Crimea, Odesa, and Moscow, sons’ weddings, and cityscapes.

Rufim Shkolnikov’s wife Oleksandra with a friend, Kamchatka, 1950s. Photo Rufim Shkolnikov. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Among the photos, you can also see military exercises at training grounds, portraits of colleagues. He documented feasts with his family, visits to the cemetery, and the usual farewells at the railway station. In addition, he recorded the life of the Soviet army in East Germany, where he served in the 1960s, bathing in a field bathhouse, the passage of Soviet military equipment through the streets of Germany, and the architecture of socialist realism. Shkolnikov’s archive eventually developed into a journal of Soviet life, a military biography, and a family saga at the same time.

Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Rufim Shkolnikov traveled a lot because he served in the armed forces of the USSR — he was constantly transferred from place to place. After serving in East Germany, he was transferred to the 24th Mechanized Brigade of the Iron Division named after Prince Danylo Halytskyi, based in Yavoriv. There, in Lviv, he died. After that, his Lviv apartment was sold, and the bag with photo films was saved from going to the dump by the founder of the museum of abandoned things Volodymyr Travnikov — he was a neighbor of Shkolnikov and helped to clean the apartment after his death. The wife of the soldier also died, and his sons live in Russia and do not visit their father’s grave. They serve in the military.

Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Some events from the life of army captain Shkolnikov do not require textual explanations or footnotes — much is clear from the photos. However, the editors do not claim to be absolutely objective, so they limit themselves to neat “probably” and “at least” when concluding the circumstances of Shkolnikov’s life only from the photos.

Rufim’s son Ihor. Kamchatka, 1957. Photo Rufim Shkolnikov. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Ihor with his mother Oleksandra. Kamchatka, 1957. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Shkolnikovs Oleksandra, Rufim and son Ihor. Kamchatka, 1957. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Ihor Shkolnikov (first from the left), Kamchatka, 1957-58. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Ihor Shkolnikov. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Probably, the departure of the Shkolnikovs from Kamchatka, 1959. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov -

Probably, the departure of the Shkolnikovs from Kamchatka, 1959. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Ihor with his mother Oleksandra. Probably, Tula region. Photo: from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov -

Ihor (fourth from the left) in Moscow with his grandfather (probably) and father Rufim (first from the left), early 1960s. Photo: from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Tula region, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Dmytro holds the medal of the deceased at the funeral, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

The Shkolnikovs came from the maternity hospital after the birth of their youngest son Dmytro. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

East Germany

-

Dmytro Shkolnikov, East Germany, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Dmytro Shkolnikov, East Germany, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Oleksandra Shkolnikova in Dresden. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov -

Ihor Shkolnikov, East Germany, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Dmytro and Ihor Shkolnikov, East Germany, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Shkolnikovs at the family cemetery, Tula region, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

East Germany, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov -

East Germany, 1960s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

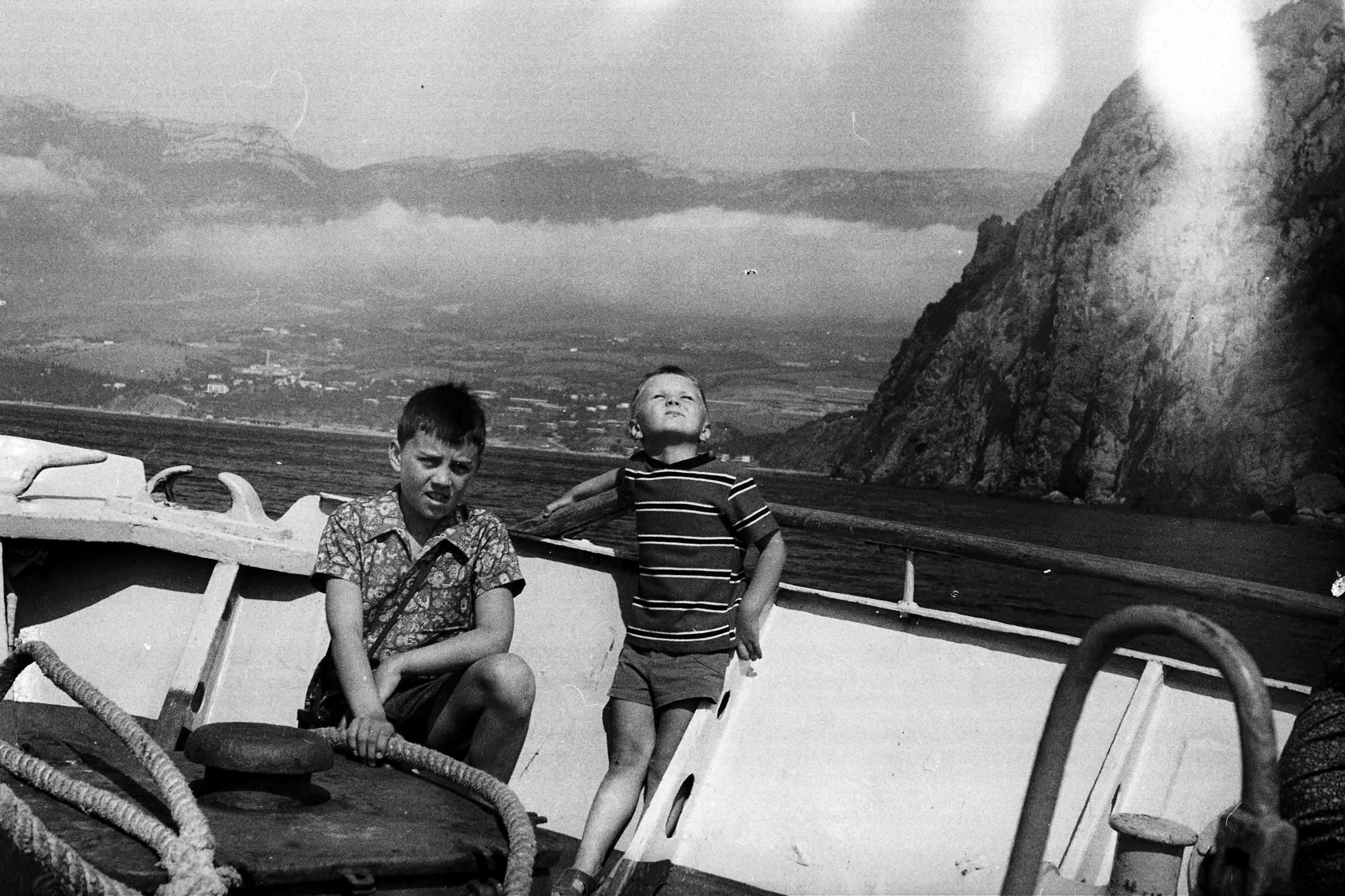

Crimea, 1969

-

Ihor and Dmytro on vacation in Crimea. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

The Shkolnikovs in Crimea. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov -

The Shkolnikovs in Crimea. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

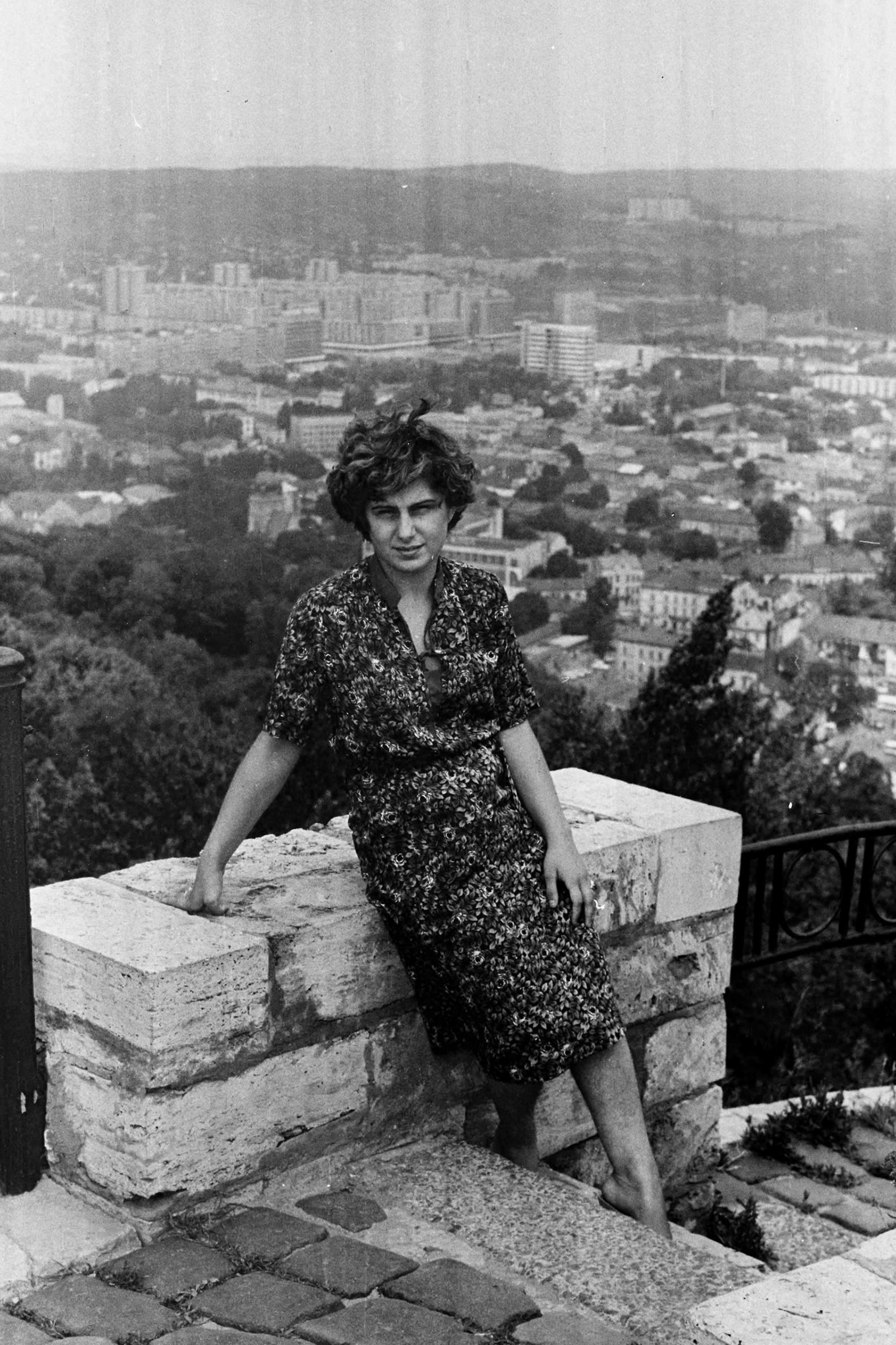

Lviv, 1970s

-

“You Just Wait!” cartoon at home in Lviv, 1971. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Lviv, 1970s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Lviv, 1970s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Ihor Shkolnikov (first from the left). Lviv, 1970s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Ihor’s military oath, 1970s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

Ihor Shkolnikov, 1970s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

1980s

-

Lviv, 1981. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

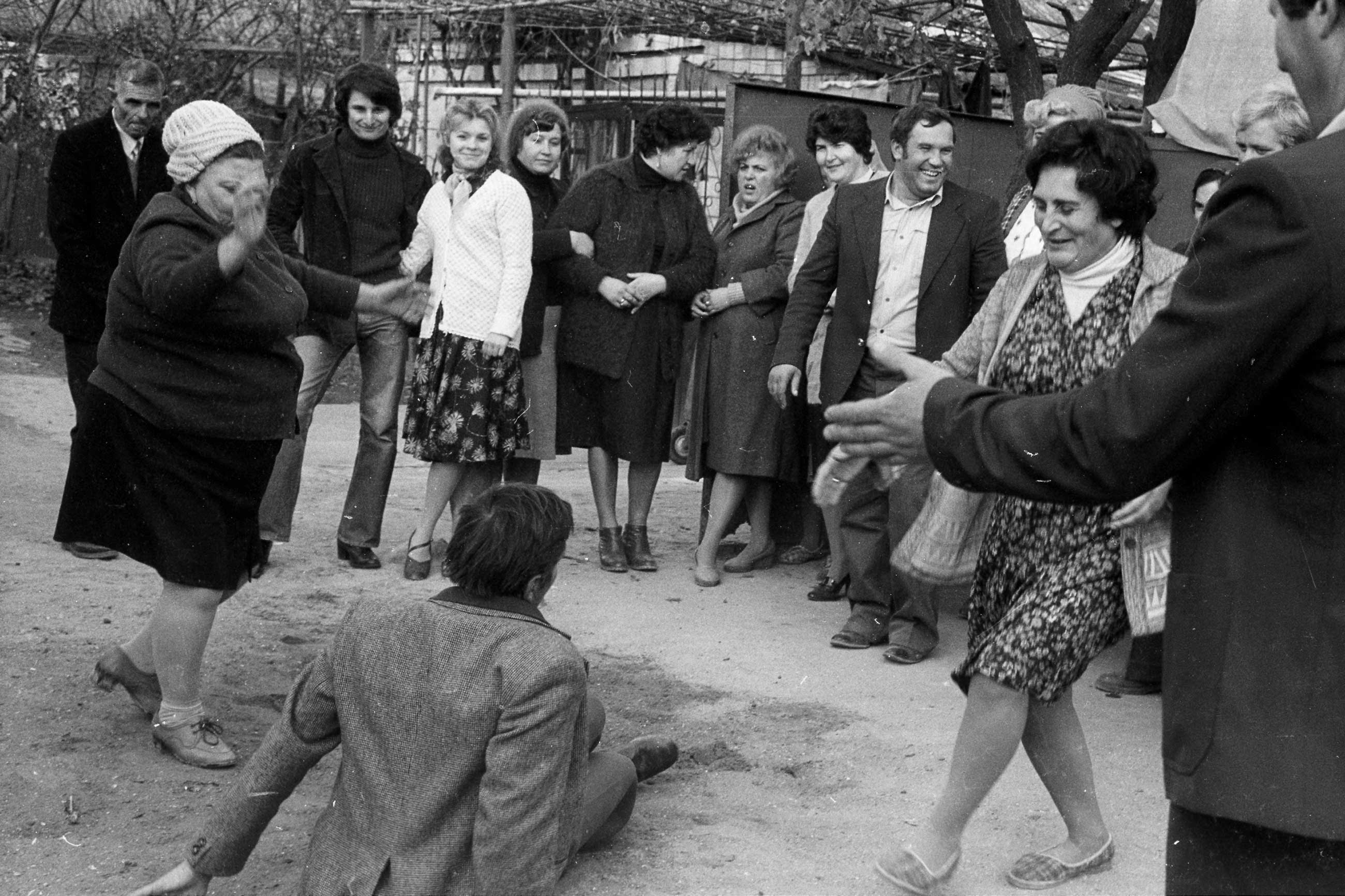

The wedding of Ihor, Odesa. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

The wedding of Ihor, Odesa. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

The wedding of Ihor, Odesa. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Dmytro’s military oath, Lviv, 1980s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Lviv, 1980s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Lviv, 1980s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Lviv, 1980s. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

With his son lieutenant Ihor. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

View from the balcony of the Shkolnikovs in Lviv. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Dmytro with his father at home in Lviv. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Oleksandra Shkolnikova with her daughter-in-law. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Granddaughters of the Shkolnikovs. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Oleksandra Shkolnikova with her sons. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Rufim Shkolnikov with granddaughters. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

Rufim Shkolnikov. Photo from the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov

-

From the archive of Rufim Shkolnikov