“Mom, I’ll Be Back.” The Story of a Woman Who Lost Her Son in Mariupol

On May 9, the Russian occupiers held a cynical “celebration” of Victory Day in Mariupol. At the same time, the Russians continued to retrieve the bodies of dead citizens, including women and children, from under the rubble in the ruined city. The exact number of civilian and military casualties is still unknown, and no one can be sure that we will ever know it at all: corpses that fall into the hands of the occupiers are burned or buried in mass graves. Zaborona journalist Polina Vernyhor collects stories of those who survived the horrors of the war in their native Mariupol. We are talking about Kseniya Kayan, who lost her son Bohdan under fire and had to take her wounded mother out of the destroyed city.

On May 15, Bohdan Pylypenko was to turn 17 years old. He was a sophomore at the Marine Lyceum, was a foreman there, and dreamed of a career as a sailor – he wanted to be like his grandfather. When the war broke out, the guy tried to help not only his loved ones but almost strangers. And Bohdan was sincerely indignant that the war was taking away his adolescence. However, it so happened that the war took away not only his adolescence but also his life. On March 11, the boy died when an enemy missile hit the house.

A golden child

Now it is difficult for me to call Bohdan a child because at the age of 16 he was already a man – serious, sensible. As a child, he had read all the books that were at home. He had a good nature: he constantly took kittens and puppies from the street – we sheltered them, and then found owners for them. Bohdan was very responsive, trying to help everyone he could.

He also showed artistic talent – in kindergarten and school, he played in all performances. Bohdan was loved by kindergarten teachers, school teachers, and lyceum teachers because he was responsible, wise, well-read, educated, and very intelligent.

He studied well because he knew what he wanted and aspired to it. At the same time, we never forced him – the last time I looked at my son’s school grades was when he was in first grade. He was fluent in Russian, Ukrainian, and English, and spoke well French. He understood history very well, was fond of reading, wrote stories, and had his own YouTube channel. He loved photography: we gave him a professional camera, and he invited people to shoot via Instagram.

Bohdan was a leader, but very democratic. He always treated people with empathy. He was so fair by nature that he always supported the weak, and went to help them and protect the offended. The child had a heart of gold.

His grandfather was a sailor and spent almost his entire life at sea. Bohdan admired him – how educated his grandfather was, what a high-class professional he was. Therefore, he decided to enter the Mariupol Marine Lyceum. He went to apply with his friend – both passed the competition. Of the 50 applicants for the budget places, only two were selected. I didn’t even know that he went to take exams. Bohdan just then showed me the results and said: “Mom, I entered.”

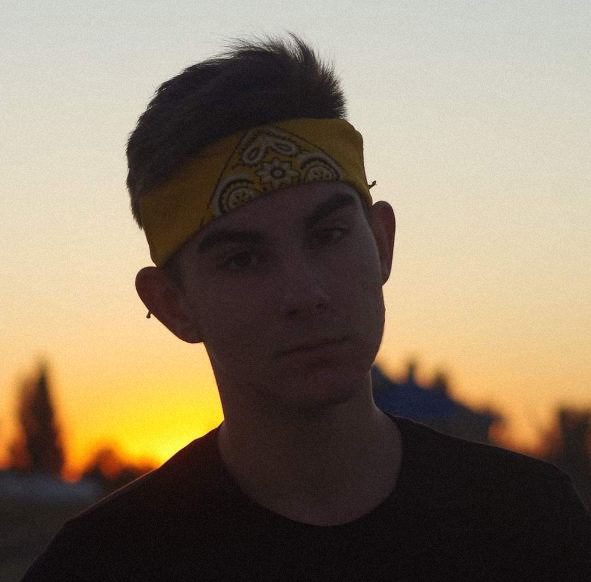

Bohdan Pylypenko with his mother Kseniya Kayan. Photo courtesy of Kseniya

“Mom, the war has begun”

On the morning of February 24, Bohdan woke me up with the words: “Mom, the war has begun. We need to collect things and think about what to do next.” At first, we planned to go to relatives in Kharkiv. As the bombing began all over Ukraine, including in Kharkiv, it was not very clear where to flee. Our evacuation plan failed.

We lived on the ninth floor of a high-rise building opposite the Mariupol Commercial Port and the Shipyard. This Primorsky district is a rather dangerous place.

We decided that it was safer to move to our grandmother in the city center. There was a small cellar in the garage – we knew we could hide there, and when a little more information appeared, we could think about where to evacuate.

Bogdan fortified our house: he collected earth in bags and closed the windows with them. He instructed everyone, found a safe place in the house, where the rule of two walls applies. He ran around the neighbors, helped, and chopped firewood, as people cooked food on a fire. In the early days, when some stores were still open, he spent his money to buy cigarettes and chocolates and gave them to the Ukrainian military. He went to the blood transfusion center to donate blood, but as a minor, he was not accepted.

I remember him running around the neighborhood with a friend to charge the phones of all the old women on the street from the generator. Bohdan kept in touch with his friends from other cities, trying to find them a safer place and housing in western Ukraine.

One day we were sitting with him, talking, and he said, “Mom, I could be dating a girl now. And because of this war, I have to dig the ground and fortify the house. “He was very indignant at the injustice of this world and the war. But he did his best to save and help everyone around him.”

Bohdan Pylypenko. Photo courtesy of Kseniya

One day a shell hit a nearby house. Two old women lived there, their doors and windows were jammed. Bohdan rushed to help them – he broke the windows, pulled out these ladies through the windows, and took them to our house. I ran after him down the street and asked him to return home so that nothing would happen to him. He stopped, looked me in the eye, and said, “No, Mom, I have to do this. I will definitely be back, and you go home.”

“I didn’t even have a chance to say farewell to my son”

On March 11, we were all at home: me, Bohdan, my mother, my sister with her husband, and my niece. Missiles from Grad MLRS hit our house and I was deafened. When I regained consciousness, I took a flashlight from my pocket and checked the pupil response of everyone who was with me. If there is no pupillary reaction, it is either a coma or death. Bohdan and my sister’s husband died immediately. I had to save everyone I could save.

My mother was unconscious, but her pupils reacted to the light. I began to provide first aid. At that time, I saw one task before me – to save those who could be saved. And that’s all.

Neighbors came from somewhere, and a military man came. They took us out and sent us to the hospital. That is, I had no chance not only to bury but even to say farewell to my son. He was wounded in the back of the neck. The only thing I managed to do was put a warm sweater under his head and covered his face with a towel.

Reflection on the murdered son began when we reached the territory controlled by Ukraine. This happened only on April 9 – before that, we had to go through a lot.

Kseniya with her son Bohdan. Photo courtesy of Kseniya

In the line of fire

After the shelling, we ended up in the hospital. I was there for four days and all this time I volunteered: treated wounds, helped to give birth, treated the stumps after amputation, fed the children in intensive care, and carried out the corpses. We had to do everything because there was a catastrophic shortage of medical staff. At that time, it was the only hospital in the territory controlled by Ukraine – pediatric traumatology near the bombed maternity hospital. The rest have already been destroyed.

We didn’t know if my niece would survive. She is 14 years old. She was severely cut and lost a lot of blood. However, she was resuscitated. Mom, niece, sister – all were bedridden.

The flow of patients was such that people were simply piled up in the corridors. You walk through the hospital, and you have blood under your feet. Prior to that, we experienced the constant shelling, which did not stop day or night. The planes flew like minibusses every 15-20 minutes. Sometimes you go to the intensive care unit to wash or feed a child and you don’t know whether a bomb will be dropped on you now or not. Maybe this will be the last thing you do in life.

The conditions in the hospital were unbearable. The humanitarian crisis in the whole city came on March 2, when the lights were turned off, communication, Internet, water, and gas disappeared. By that time, all shops and pharmacies had already been bombed and looted. There was a lack of medicines. We could not even just wash our hands, because the water was only drinking. And under such conditions, doctors continued to work, to perform their duties.

People who were there behaved differently. Someone was sitting in a corner and said he was not going anywhere because the walls here seemed to be thicker. Someone, like me, volunteered, helped – did everything he could.

Four days later, my mother and I were told to go to the bomb shelter because we had legs. Only bedridden patients were to remain in the hospital, as there were not enough beds for everyone.

I agreed with the guys from the hospital to look after my sister and niece. A volunteer took me and my mother. He said: “I’m going to the bomb shelter. Choose the drama theater or the philharmonic. I answered: to the philharmonic. Two days later, an aerial bomb was dropped on the drama theater.

We spent 16 days in the philharmonic. At that moment, it was under fire from both sides, just in the line of fire. It was impossible to get out of the basement even just to take out the bucket, which everyone used as a toilet. We haven’t seen the sun in all these 16 days.

Every ascent to the first floor of the philharmonic to take a portion of food prepared on the second floor is a risk to your life. I didn’t know if I would come back or not. But my mother’s life depended directly on me because she was very weak: she could not walk alone for three weeks, lost a lot of blood, and suffered a concussion.

The conditions in this bomb shelter were terrible. In fact, it was not even a bomb shelter – just a basement. There was no medicine. My mother developed bilateral pneumonia, and I miraculously managed to find a woman who had antibiotics. Thanks to this pack of antibiotics, my mother managed to survive.

Bodies of those killed on the streets of Mariupol, May 21, 2022. Photo: Leon Klein / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Escape

On the sixteenth day, I realized that I had to go because very heavy bombardments had begun. It was scary to stay under the rubble. We gathered a group of 15 people and agreed that we would go down towards the sea, away from the line of fire. We had information from a man who got to the philharmonic from the Primorsky district. He said it was quieter in the Primorsky district now. The main thing is to get there. I carried my mother for three kilometers. We went under the Grad shelling.

We got to our house. There was a vehicle in the garage – before the war, we had just charged the car battery. I filled a car with people and took them to Melekine [a village in the Donetsk region 20 kilometers from Mariupol]. Unloaded a car. Twice more I returned under shelling and took away people.

It was decided to stay in Melekine and wait for the city to open, because on April 8 Mariupol was closed for entry. We were waiting for the opening so that we could look for our sister and niece.

The entrance was never opened. On April 8, we managed to catch a very little mobile connection – via Viber I received an SMS from the [mobile] operator of the so-called DNR. I found a person who had this operator’s SIM and called the number who sent the message. It was a niece. She said that she and her mother were taken to the DNR. They are both bedridden and are now in hospital.

Destroyed houses in Mariupol, April 29, 2022. Photo by Leon Klein / Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

“Responsibility lies not only with the Russians”

I believe that not only Russians are responsible for my son’s death. Actually, not only my son but all the civilian victims in Mariupol. The mayor of Mariupol Vadym Boychenko left the city for slaughter. He left it on February 26, the third day of the war. He did not prepare any bomb shelters and did not take care of generators for people. Our air raid siren sounded for exactly two days. He fled and did not take care of the city.

Now he says he is worried about the residents. But it’s all crap. Every Mariupol resident knows about it. There was no centralized evacuation. The city of half a million people was simply abandoned – Mariupol was doomed from day one as soon as Chongar was mined. And the city authorities were well aware of this.

We were waiting for the green corridor. We turned on the battery-powered radio and caught the radio stations. The green corridor was never opened. When we realized that no one would save us and that we had to get out ourselves, there was nothing we could do. The city was completely surrounded, shot from all sides.