Self-Immolation as a Protest. Why Do People in Post-Soviet States Set Themselves Aflame

In early October, 49-year-old war veteran Nikolai Mikitenko committed self-immolation on Independence square in Kyiv. This was his way of protest against the military policy of the current Ukrainian government—particularly, the withdrawal of troops in Donbass. Activists around the world for decades resort to self-immolation as a form of protest when other means seem ineffective. Zaborona journalist Alyona Vishnitskaya investigated how self-immolation has become a way to reach out to the authorities and public, and why the authorities are usually silent in response.

Three Twenty-Five

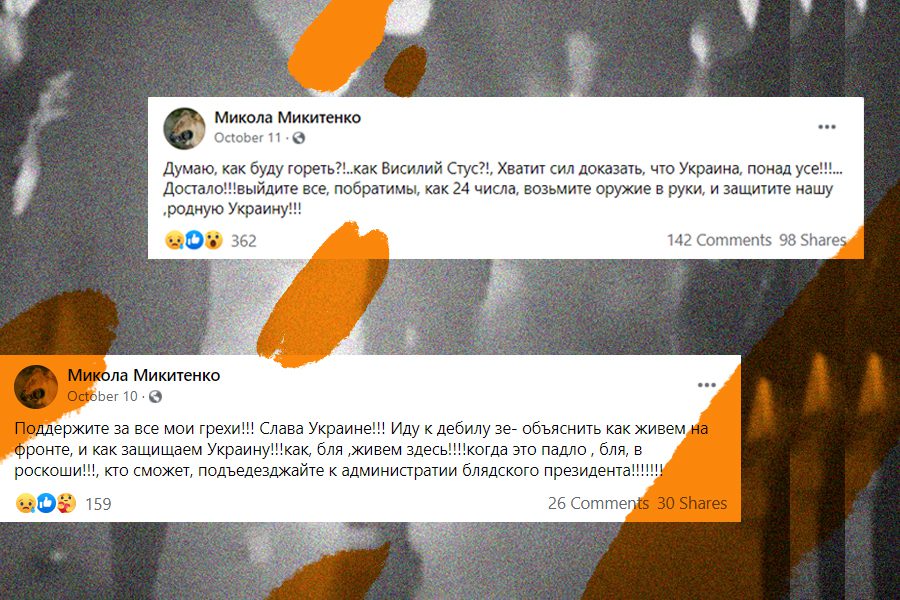

On the evening of October 10, Nikolai Mikitenko, as always, was dressed in his military uniform. He had been back from the war for six months, yet he rarely took off the uniform—he didn’t like to. Later that night, he wrote several posts on Facebook saying that he was “strong enough to prove that Ukraine is above all else,” and wondering if he would “burn like Vasyl Stus.” At 3:25 he posted a story that read: “I just want Ukraine to be independent.” Then a few minutes later, he came to the Kyiv Founder’s Monument and Fountain, put a backpack with his documents off to the side, doused himself with three liters of gasoline, and set himself aflame.

“He didn’t think for a minute,” says his daughter, Yulia. She watched the surveillance video dozens of times: “Some people ran up to him and tried to push him into the fountain. But he just simply stood there, not allowing them to help. He cursed and screamed in pain that Zelensky would not let him go to war. Eventually, he tripped over the curb and fell into the water.”

The ambulance arrived immediately. He woke up, gave the phone number of his deceased mother, and, before losing consciousness again, asked: “Why did you save me?”

The doctors gave Nikolai no more than a few hours to live. His body was almost entirely burned. The hospital claimed that he was “non-transportable.” He was injected with morphine to help moderate the pain and put in a medically-induced coma the next day.

He was in a coma for two days. Yulia never got a chance to go to his ward: “The doctors said he was unrecognizable, his head was the size of a TV. I didn’t want to see him like this.”

She believed until the end that he would survive.

He had always been a lucky man—he had survived where no one else could. It wasn’t the case this time.

Yulia Mikitenko

Her father lived for three more days. Yulia found it in her heart to look at him only in the morgue. Nikolai Mikitenko was dressed in military uniform and buried in a closed coffin.

Returning Back

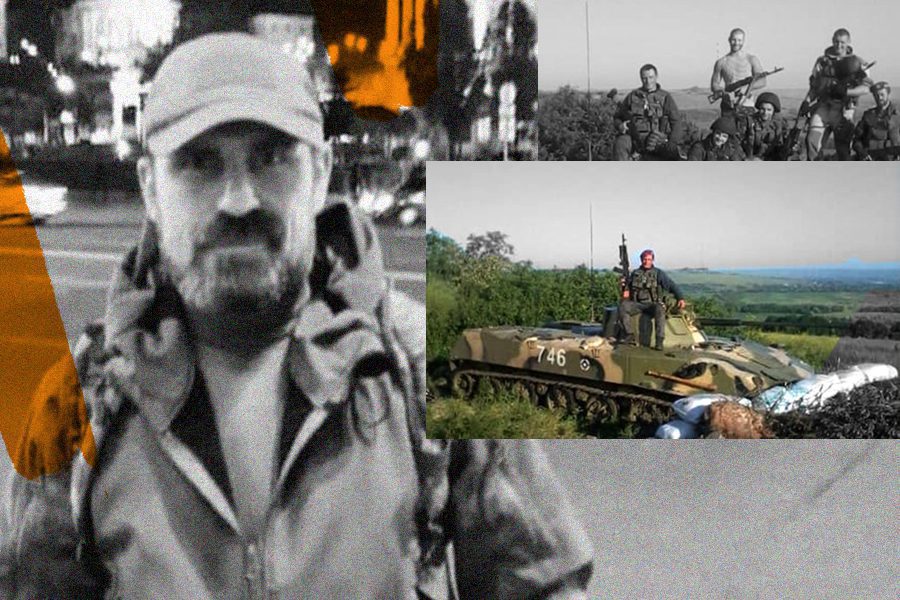

Nikolai liked the military uniform ever since he was a child. His father was a military man, he served on a submarine and fought during the cold war. Nikolai had a lot of respect for his father and, looking at his military uniform, wanted to be like him. Nikolai served in the Tank Corps until the 80’s when he was sent to war in then-Yugoslavia. Then he served in customs. He received two degrees, one in law and the other in history. Worked as a tour guide.

“He had a wide range of interests, but what he loved most was being around the military. He supported Afghan alliances and could always find something in common with them. This brotherhood was important to him,” recalls Yulia. His brother Dmitry also joined the military, he served in the Berkut battalion. He left because he didn’t agree with the orders on the Maidan.

Nikolai was on the Maidan almost constantly, and during the crackdown in February 2014, he received a concussion. From there, in the first ranks, he went to war. He fought in defense of Sloviansk and evacuated bodies from Karachun Mountain in May. Back then pro-Russian separatists shot down a military helicopter as it transported food, water, and body armor to the Ukrainian military base, killing 12 National Guard soldiers including Major General Serhiy Kulchytsky. The armored personnel carrier, which Nikolai used to transport the bodies, blew up on a mine. He suffered severe spinal injuries but survived. “When I came to visit him in the hospital, he said, “You didn’t have to come. I’m doing just fine.”

He never complained. He was outgoing and charismatic,” says Yulia. “He loved ladies, was a Don Juan of sorts. We like to make everyone a saint. He certainly wasn’t. But I don’t know a single person who wouldn’t like him.

Yulia Mikitenko

Then there was long-term rehabilitation. Due to numerous injuries, Nikolai was dismissed from the National Guard, and his military career could have ended there.

“He had an injury, a good pension, two university degrees, a wide range of interests and acquaintances,” says Yulia. “He wouldn’t have trouble finding himself here, but he was always drawn to war.”

After the dismissal, he joined a dozen military units, including the Right Sector, 54th and 58th Mechanized Brigades. As soon as one unit left a combat zone, he would join another one and return to the war.

He rarely talked about the war with Yulia until she went there herself. As soon as she graduated with a bachelor’s degree in philology from Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, she joined the Kyivan Rus battalion.

“It was a well-thought decision. I wanted to graduate first, and my husband supported it. I was scared. I didn’t even know how to hold and disassemble a rifle, he taught me everything.”

In February 2018, her husband, intelligence officer Ilya Serbin, was killed during an attack near the Svitlodarsk Bulge. Yulia continued her service.

She says that over time, both fear and survival instinct faded:

Fear of death is normal. But soldiers often go beyond that fear—they know it when the attacks no longer scare them. From my dad’s poems, I knew that he didn’t have any fear. He felt a longing for home and family, but not fear. That could be caused by the war or even by the attacks at Maidan.

Yulia Mikitenko

“There was also an adrenaline rush,” Yulia adds. “t felt like an addiction that made you want to go back to war over and over again.” When Nikolai was not at war, he spent almost all his time in the hospital—rehabilitating from a back and neck injury, talking to a therapist, visiting his battle brothers, and getting volunteer help for his units.

“Many veterans would agree with me if I say that it’s difficult to adapt to civilian life after the war,” she says.

“It’s hard to find a community that values brotherhood as much as in war and people who would be quick to understand each other,” she explains. Her father started talking about his experience of war only after she saw it with her own eyes. At the end of his service, she learned how he had collected rainwater and cooked lizards when there was no food or water at all.

The Living

Nikolai retired from the 58th brigade in March and started making plans in Kyiv. Yulia says that her father knew that it was okay to talk to a therapist and work on his issues. A week before the self-immolation, he arranged meetings, and the night before he told his tenants that he was going to pick mushrooms in the forest the next morning.

It seemed as though he was trying to find his place in civilian life, but the troop withdrawal agreement had got him down. It was signed back in 2016. Under the terms of the agreement, armed forces from both sides must withdraw a kilometer from three front-line areas in the Luhansk region and hold a ceasefire. Yet, the ceasefire was violated, and the agreement broke down. In 2019, the agreement was revived, and the troop withdrawal process was re- initiated. However, this again became one-sided—despite the agreement, attacks were recorded from the troops, who had not taken down their fortifications.

The decision to withdraw troops was met with criticism. For instance, because the withdrawal of Ukrainian forces would leave more than a hundred civilian houses of Zolote in the buffer zone, and if the troops are withdrawn 2-3 kilometers away from the demarcation line, the Ukrainian frontline would be pushed to the city center. On top of it, dozens of inhabited settlements would end up without the control and protection of the Ukrainian army.

Yulia says that the decision of the authorities to withdraw the troops broke her down:

I spoke with those who were on the frontline at the time. They were in absolute shock—all the heavy weapons were taken away. They couldn’t even protect themselves, let alone attack. Of course, they were somewhat armed at the second frontline. Knowing the efficiency of our army, it was clear that they would not even have time to let out a squeal.

Yulia Mikitenko

It was hard to hear and see this, she adds, so much so that she even wanted to do something to herself, “to disappear so she didn’t have to see it”. She thought about it out of despair and inability to change the situation.

“The troops had to withdraw from the Svitlodarsk Bulge, the place where my husband died. It was a great loss for my father as well.” Nikolai would call his daughter from time to time to talk about it. “How is possible? Fuck, how is it even possible?” he would say.

Now Yulia serves as a teacher and is also in command of a platoon at Ivan Bohun Military Lyceum. She doesn’t plan to return to civilian life—she’s afraid she won’t be able to adapt.

“I have skills that cannot be applied in civilian life. But most of all I’m scared to hear ‘We never sent you there.’ That’s probably why I never use my veteran ID in public transport. That is part of the reason why veterans go back to war—you will never hear it from like-minded people.”

After her father’s death, Yulia cried twice: when she first found out and at his funeral. She says she can’t let herself cry because there are more important things to do—raise public awareness about the government’s neglect of veterans and their needs and try to change it.

Numbers

“Self-immolation is a method of suicide that people resort to in an attempt to express protest and draw attention to an issue,” explains psychologist Tatyana Nazarenko. According to her, people often resort to self-immolation out of despair, dismay, and frustration with things that are going on in the world.

When we feel powerless, we have to ask ourselves if that is the only way to resolve the problem or are there other solutions. The glorification of such acts might help families to cope with what has happened, but as a society, we need to do everything to encourage people to choose more constructive ways to overcome difficulties. Psychologists recommend not to make a fuss over suicide cases in order to prevent others to follow suit, the so-called Werther effect. We must do everything possible to reduce the suicide rate.

Tatiana Nazarenko, psychologist

Any behavior and act of protest displayed by veterans is often labeled as a post-traumatic stress disorder, but it’s not the case, adds Tatyana Nazarenko: “Protest is normal. Expression of one’s position is also normal. When a person returns from war, they may or may not develop PTSD. This depends on whether a person has the resources to overcome traumatic memories, such as personal characteristics, environment, health, and experience. All this affects the mental states of veterans, as well as the process of social adjustment and rehabilitation after returning from war. Yes, many of them suffer from PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders—but so do many civilians.”

The psychologist explains that the problem of suicide needs to be addressed at all levels of society: state, civil, family, and community. Therefore, the World Health Organization has suggested a number of measures that can be taken to prevent suicide, which include creating mental health access network, particularly, raising awareness among ministries, labor and education sectors, as well as training specialists in the assessment and management of suicidal behavior.

“Suicide has historically been a taboo topic in Ukraine, and this prevents the issue from being discussed by the general public. Yet, we need to realize that suicides are preventable and do everything to prevent them,” says Tatyana Nazarenko

Tatiana Nazarenko, psychologist

Suicide, including self-immolation, is a common Ukrainian problem, explains the psychologist. Ukraine recorded the eight-highest rate of suicide in the world per 100,000 people for the overall population. According to the World Health Organization, over the past year in Ukraine, almost 10,000 people have committed suicide—about 22 people per 100,000 citizens.

On top of that, suicide is one of the most frequent causes of death among Ukrainian veterans. In February 2018, the Chief Military Prosecutor of Ukraine, Anatolii Matios reported that, according to 2017 data, 2 to 3 soldiers died due to suicide weekly. Up to 80% of them had symptoms of post- traumatic stress disorder and rejected civilian life. However, according to Radio Liberty, the Ministry of Defense did not confirm this information. They admitted the problem, but claimed that the suicide rate was “far lower”. The head of the Department of Mental Health for the Armed Forces, Oleg Gruntkovsky, did not name the exact number of suicides among soldiers, due to the confidentiality of this data.

Олег Грунтковський #Міноборони : дані про самогубства у #ЗСУ – конііденційні. Але можу сказати про тенденціі : реальна кількість самогубств є в рази меншою, ніж згадані #Матіос ом цифри (2-3 на тиждень) pic.twitter.com/YYjRLlvCwg

— Solonyna Yeugen (@SolonynaY) February 23, 2018

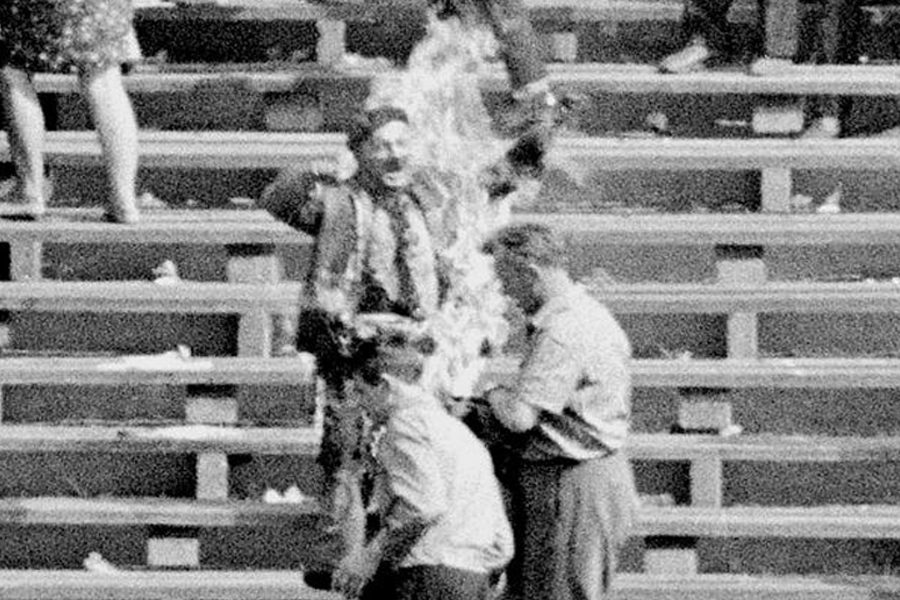

The Wave

For decades, self-immolation has been resorted to as an extreme form of protest by veterans and social activists around the world. The 1968 Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia triggered a wave of self-immolations. Protests against the Soviet invasion swept the world, writes researcher Irina Ezerskaya. 59-year-old Polish philosopher Ryszard Siwiec was the first person to used self-immolation as a form of protest. He doused himself in gasoline and set himself on fire at a stadium in Warsaw after the harvest festival and died four days later. The self-immolation was his way of protesting against the participation of the Polish army in the invasion of Czechoslovakia.

In January 1969, 20-year-old Czech student Jan Palach burned himself in the center of Prague to stir his compatriots. After that, a wave of public self- immolations swept across the country: over the next three months, 26 people set themselves on fire, seven of whom died. Researcher Irina Ezerskaya explains that the reason for that particularly was that the totalitarian regime allowed few opportunities for resistance.

Outbreaks of protest self-immolations followed for the next few years. In 1972, 19-year-old Lithuanian student Romas Kalanta set himself on fire, screaming “Freedom to Lithuania”, and left a note that read, “Blame the regime for my death.” In 1978, Musa Mamut immolated himself in Crimea, as a sign of protest against the enforced exile of Crimean Tatars and the impossibility of their return to the homeland after rehabilitation. In 1980, retired Polish veteran Walenty Badylak chained himself on Krakow’s Main Square and set himself on fire to protest the silencing of the truth about the mass execution of Polish military officers by the NKVD in the Katyn forest in 1940.

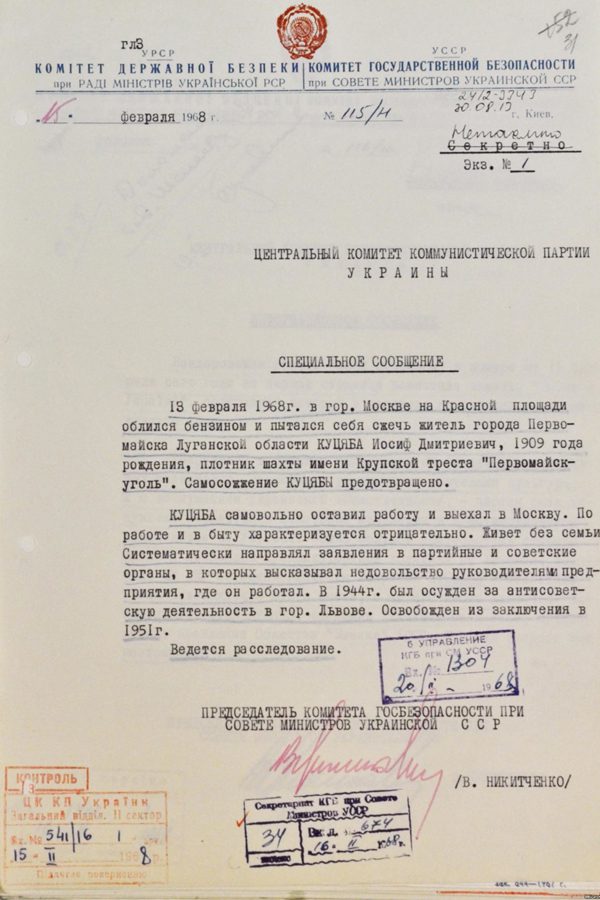

In total, 50 to 70 people committed self-immolation during the Soviet era, in Ukraine, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Latvia, and Slovakia. It’s not the final number as the KGB archives are only now being declassified, and some of the cases may still be unknown, explains Petr Blažek, Czech historian and author of Living Torches in the Soviet Bloc. After studying the cases of self- immolation, Blažek came to conclude that people resorted to it in response to a crisis situation in order to mobilize their compatriots. Self-immolation was usually an act of despair, the last resort against injustice.

In today’s Russia, most of the information about self-immolations is held in secrecy, explains the historian. We only know about those cases of self- immolation that have been witnessed by tourists or western diplomats. But who and why set themselves on fire remains unknown. They had one thing in common: all those people chose the symbolic center of power for their political protest.

“Those people devoted a significant part of their lives to fighting the totalitarian regime. They hated it. This was their life stance: they ended their lives in a way that is hard to wrap your head around,” commented the researcher on Radio Liberty.

The self-immolation rate has not declined in recent years. Last year, in Izhevsk, a 79-year-old philosopher and scholar Albert Razin, committed self- immolation outside of a government building. He held up two cardboard signs which read: “Do I have a homeland?” and “If my language disappears tomorrow, then I’m prepared to die today.” This was his way of protesting against the disappearance of the Udmurt language and culture and the inaction of authorities on the issue. He suffered burns to 90 percent of his body and died in a hospital a few hours later. In early October 2020, a Russian journalist and editor at Koza.Press, Irina Slavina set herself on fire. Her last post on Facebook read: “I ask you to blame the Russian Federation for my death.”

The First

Vasyl Makukh was the first Ukrainian to commit self-immolation. At the age of 18, he was sentenced to ten years of hard labor camps for being a member of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which he joined in 1944. He was a part of the Ukrainian resistant movement in the USSR. In November 1968, when he was 41 years old, he lit himself on fire today’s Independence Square in Kyiv in protest against the communist totalitarian regime.

His act of self-immolation was the first in post-war Europe: he did it two and a half months before a Czech student Jan Palach committed a similar act. The police and bystanders tried to put out the flames, but it didn’t help. The next day, he died in hospital after suffering burns to 70% of his body. The Soviet newspapers remained silent about this. The news was spread only through the underground press and abroad. Those who distributed leaflets and booklets about Makukh were arrested, and the author of an article about him was accused of anti-Soviet propaganda and sentenced to seven years in maximum security prison.

In the early 2000s, researcher Viktor Tupilko opened a museum in Donetsk dedicated to the fate of Vasyl Makukh and Oleksa Hirnyk, who committed self- immolation in protest against the Soviet occupation of Ukraine. In 2014, the militants seized the museum. Most of the materials had been lost.

Deafness

After her father’s self-immolation, Yulia Mikitenko wrote an open letter to the President’s office asking for a response to the incident. But no reply or reaction followed.

“I’m not really sure if I even want to hear it,” she says. “Because I don’t know if it will be sufficient for me. I don’t want to go silent just because I was not given an answer. I did it to show that the government ignores everything that is inconvenient. They are deaf to us.”

She adds that she feels guilty. Perhaps because she could have talked to her father more or told him that she was proud of him more often.

“The living blame themselves for staying alive,” says Yulia, “Me too. But what I want the most is for him to be remembered.”

Translated by Katya Chudinova from the Respond Crisis Translation