Israeli documentary photographer Eduard Kaprov turned a minibus into a photo lab and went to the front to document the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. To create pictures, Eduard uses a complex technique from the middle of the 19th century – the wet collodion process. The same technique was used by the first military photographer Roger Fenton during the Crimean War. We spoke with Kaprov about his experience as a military journalist, his connection with Ukraine, and why “straight” documentary photography no longer impresses the viewer.

Eduard was born in Chelyabinsk in the Ural district, where he spent the first 17 years of his life. In the early 90s, his family emigrated to Israel. Kaprov’s family is historically connected with Ukraine: Eduard’s grandfathers are Ukrainians (like many Ural Jews). Eduard’s brother lived in Kharkiv, but now he has been evacuated to Ivano-Frankivsk. After moving to Israel, the future photojournalist continued his musical studies, and after serving in the army, he became interested in photography.

Kaprov worked as a photographer for an Israeli geographical journal, traveled on foot through Siberia, covered the Second Chechen War and terrorist attacks in Beslan. Kaprov says the following about himself: “I was born and raised in the USSR. As for everyone who lived in the Union, WWII [The Great Patriotic War] was a “sacred cow”. It was an unshakable symbol. The personification of good and evil. I grew up on stories of exploits, on war films and books. On grandmother’s stories about the hunger she experienced. It was a romantic image, and I and the other boys felt a little sad that we did not catch that time and would not be able to accomplish our feat.

I did not think that I would have to witness an event that was comparable in scale and the level of refined concepts of good and evil … I could not think that the symbol of absolute evil would become Russia … I could not imagine that Russia would become a symbol of absolute evil … I could not imagine what I would hear on the news that at 4:00 in the morning Moscow bombed Kyiv and Kharkiv.”

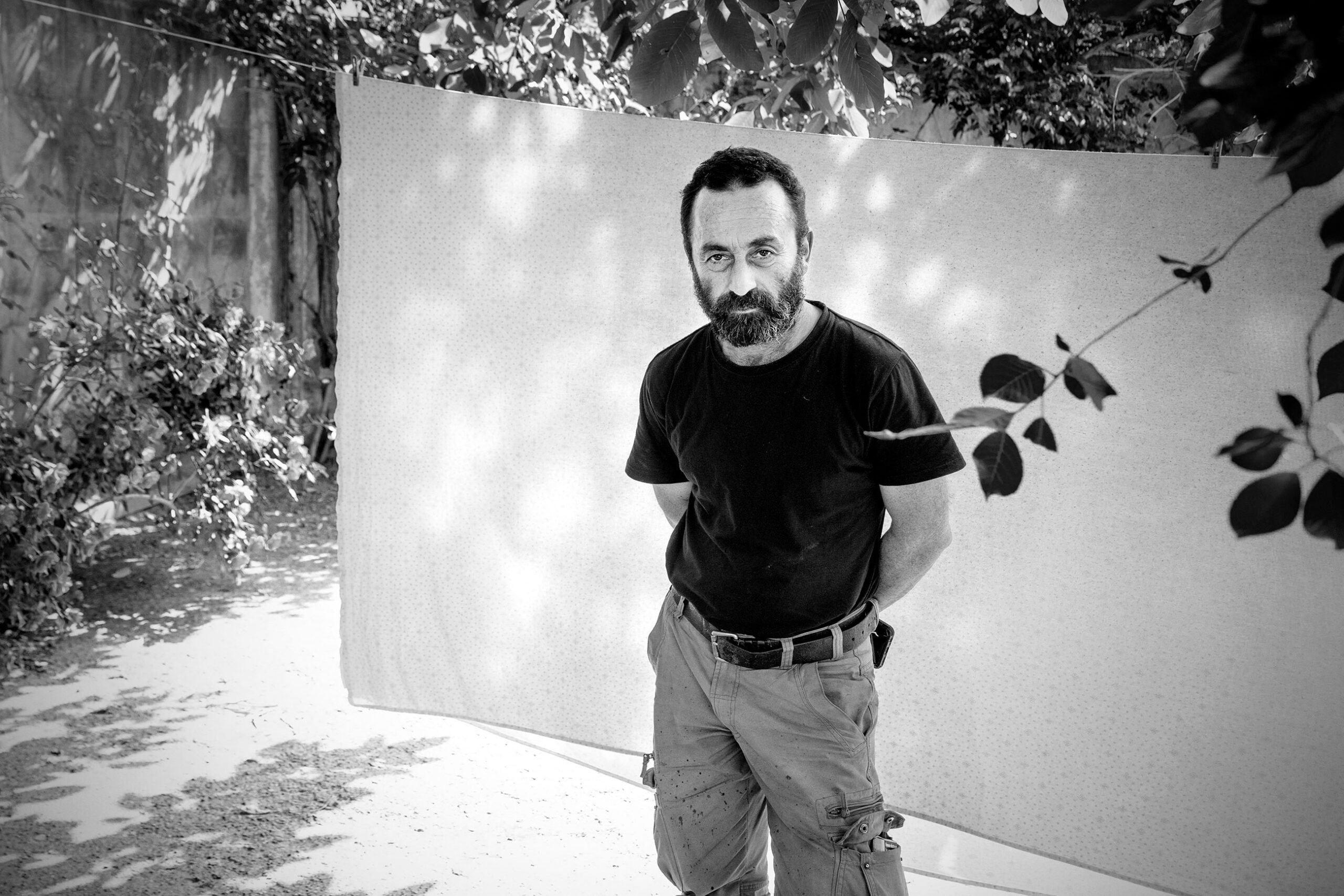

-

Eduard Kaprov. Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

After learning about the beginning of the full-scale invasion of Russia into Ukraine, Kaprov realized that this was a personal war for him. He couldn’t stand by and watch. At the end of March, he came to Ukraine for the first time. He photographed the de-occupied villages of the Kyiv region and filmed the work of volunteers in Kharkiv. You can see Kaprov’s travel photo diary here.

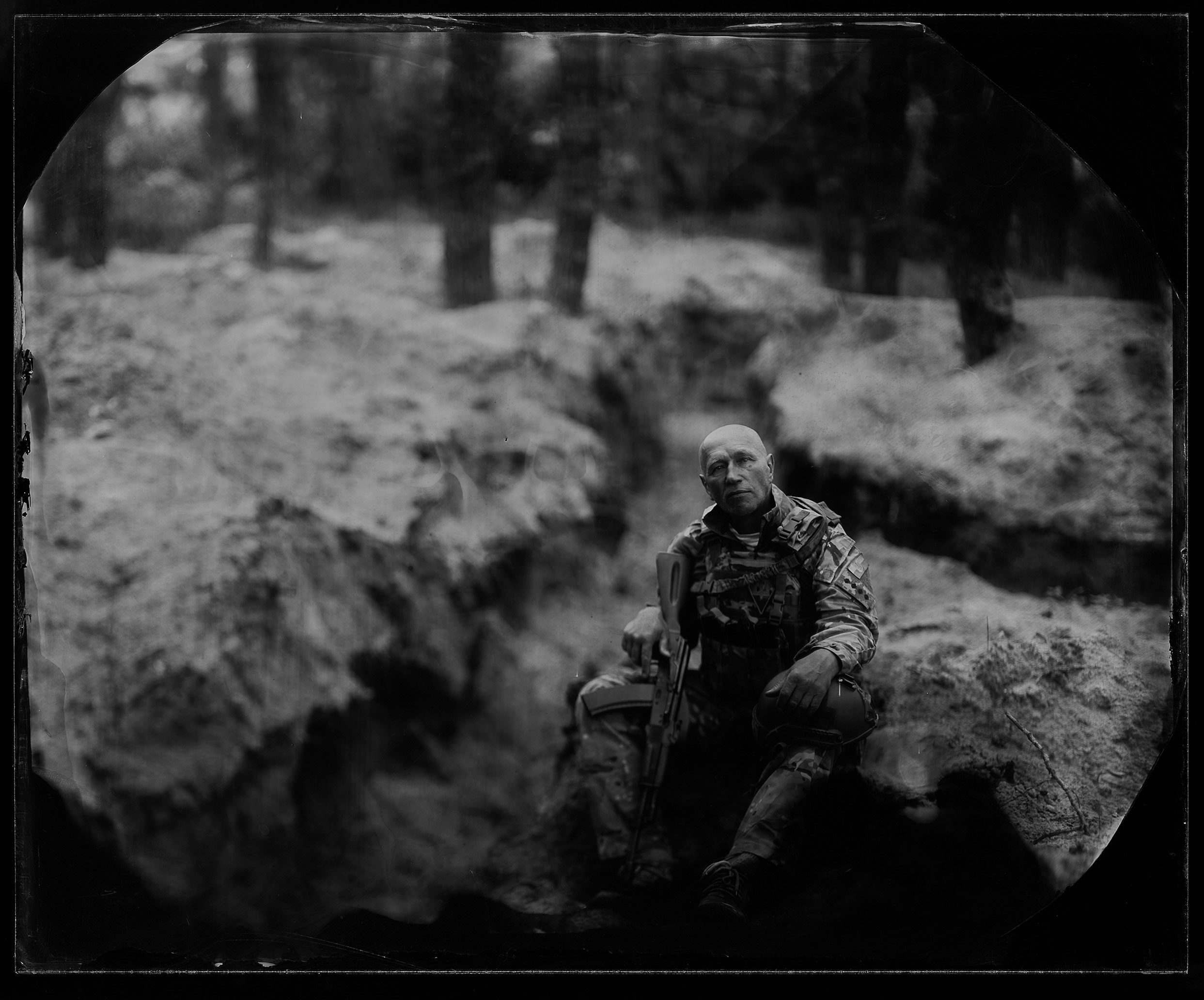

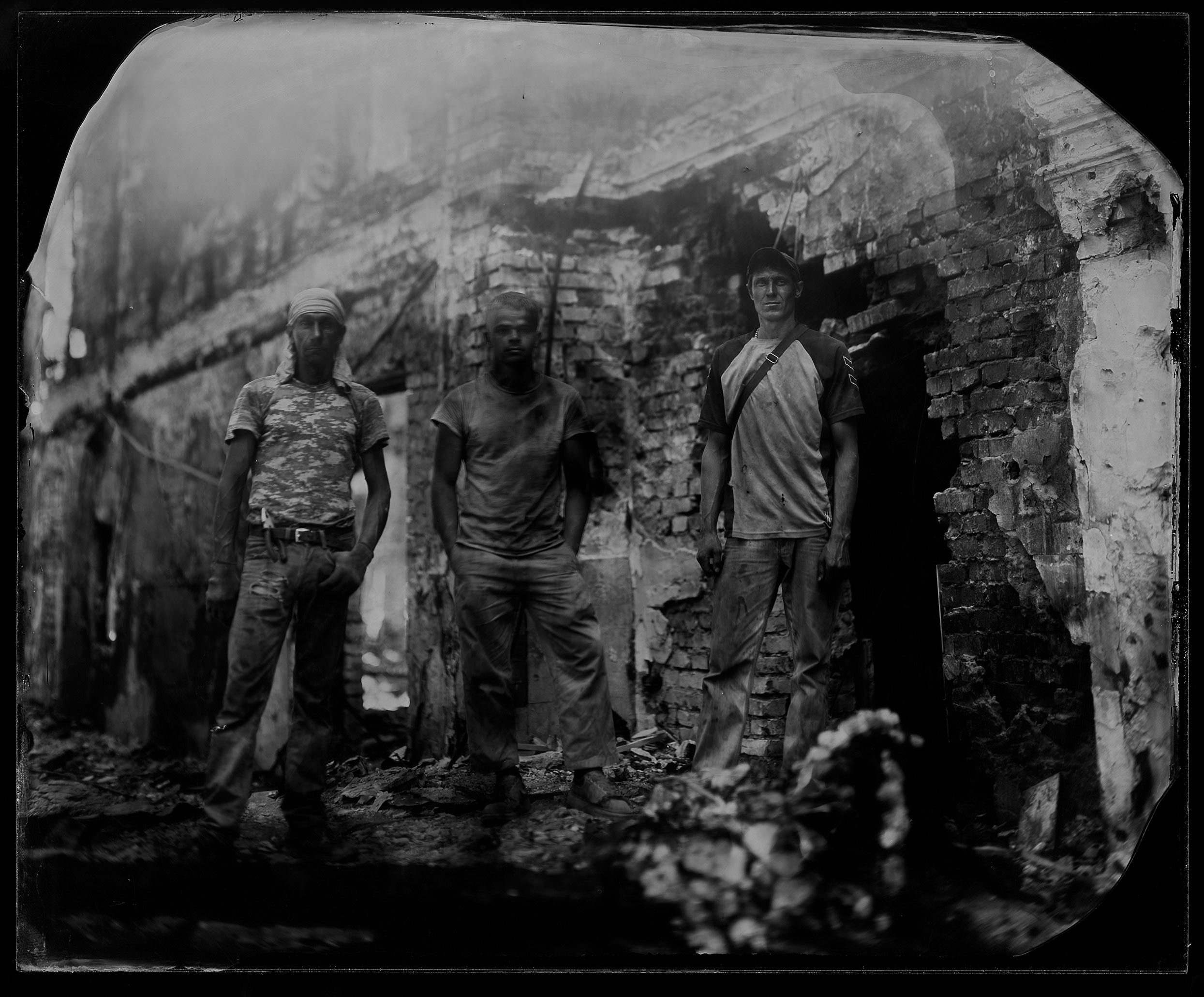

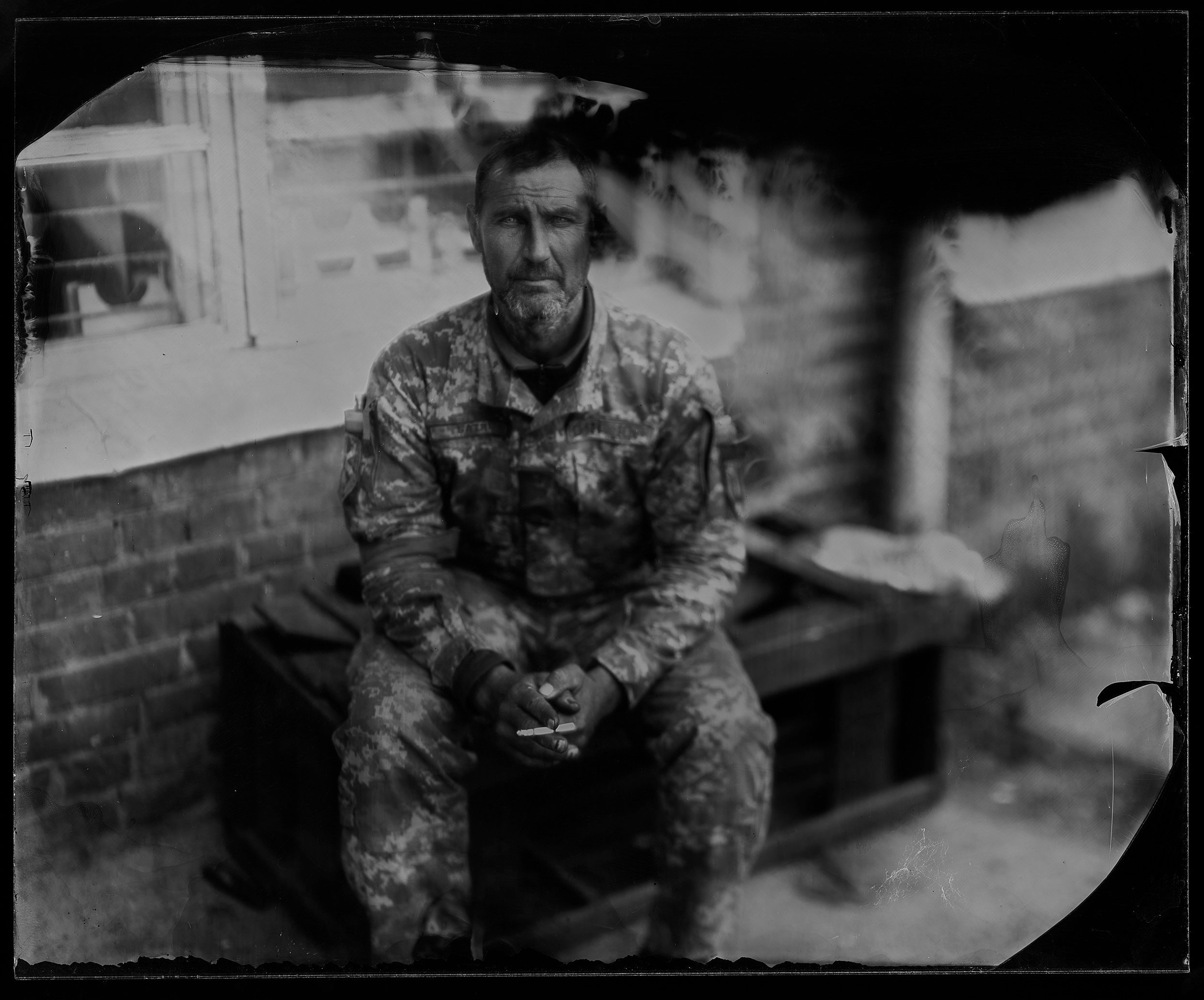

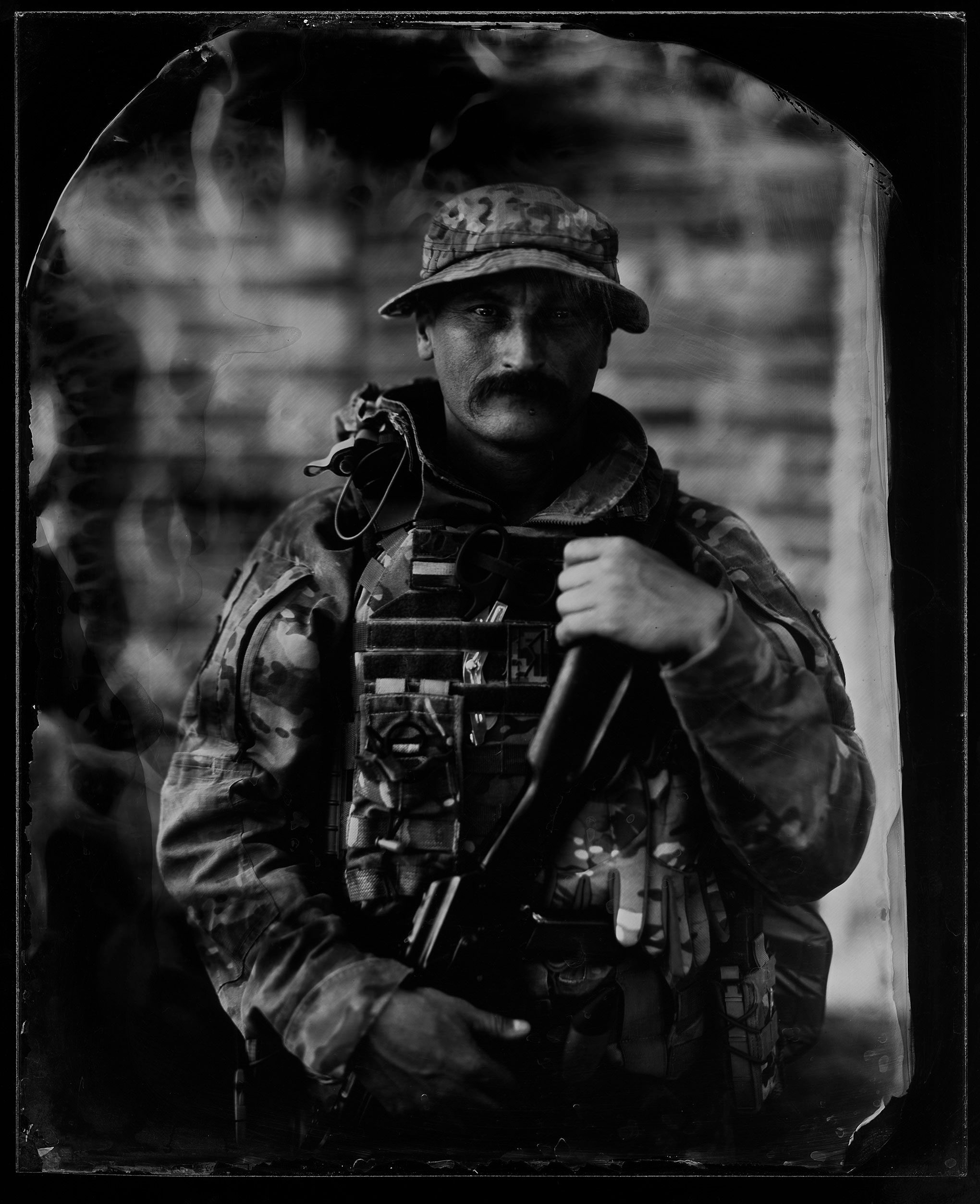

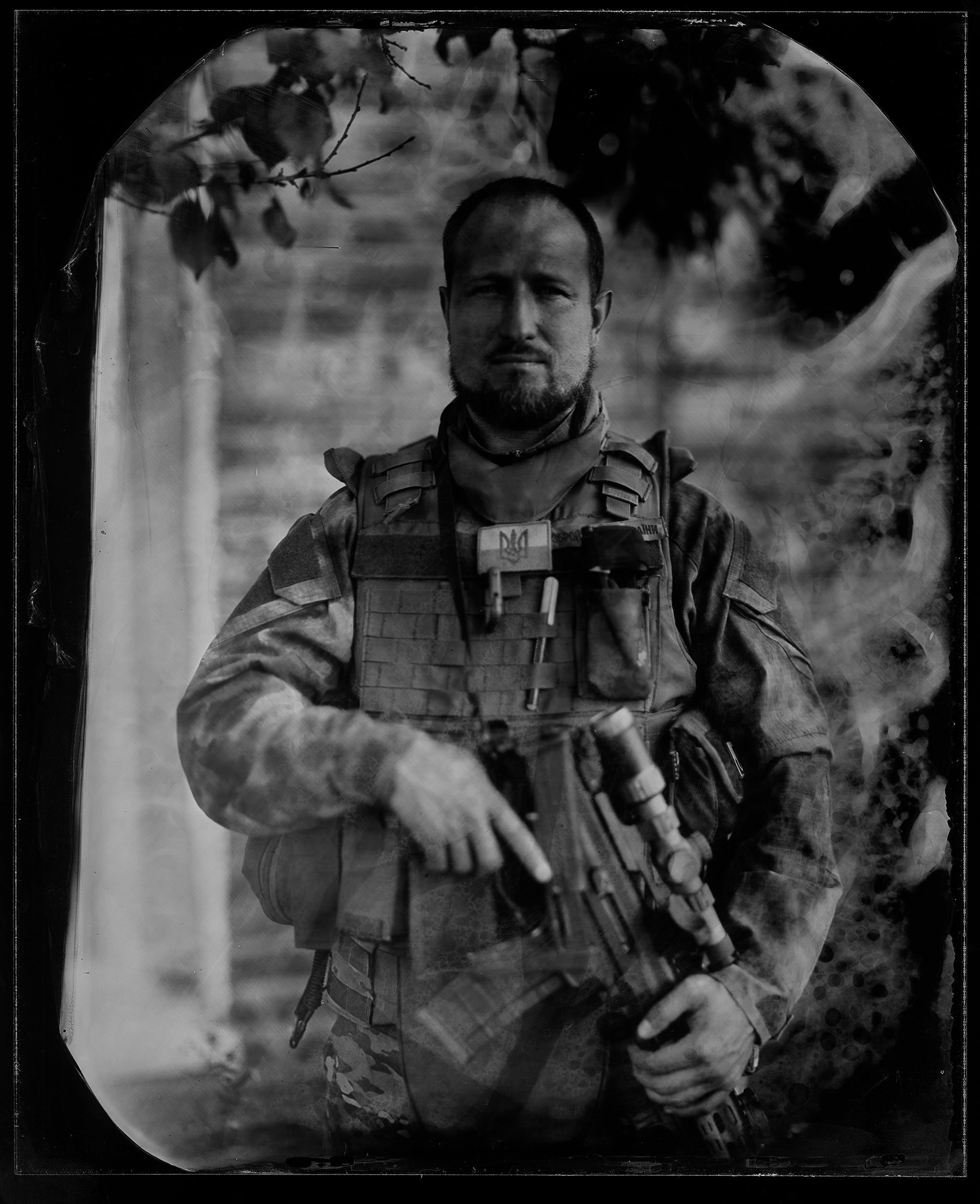

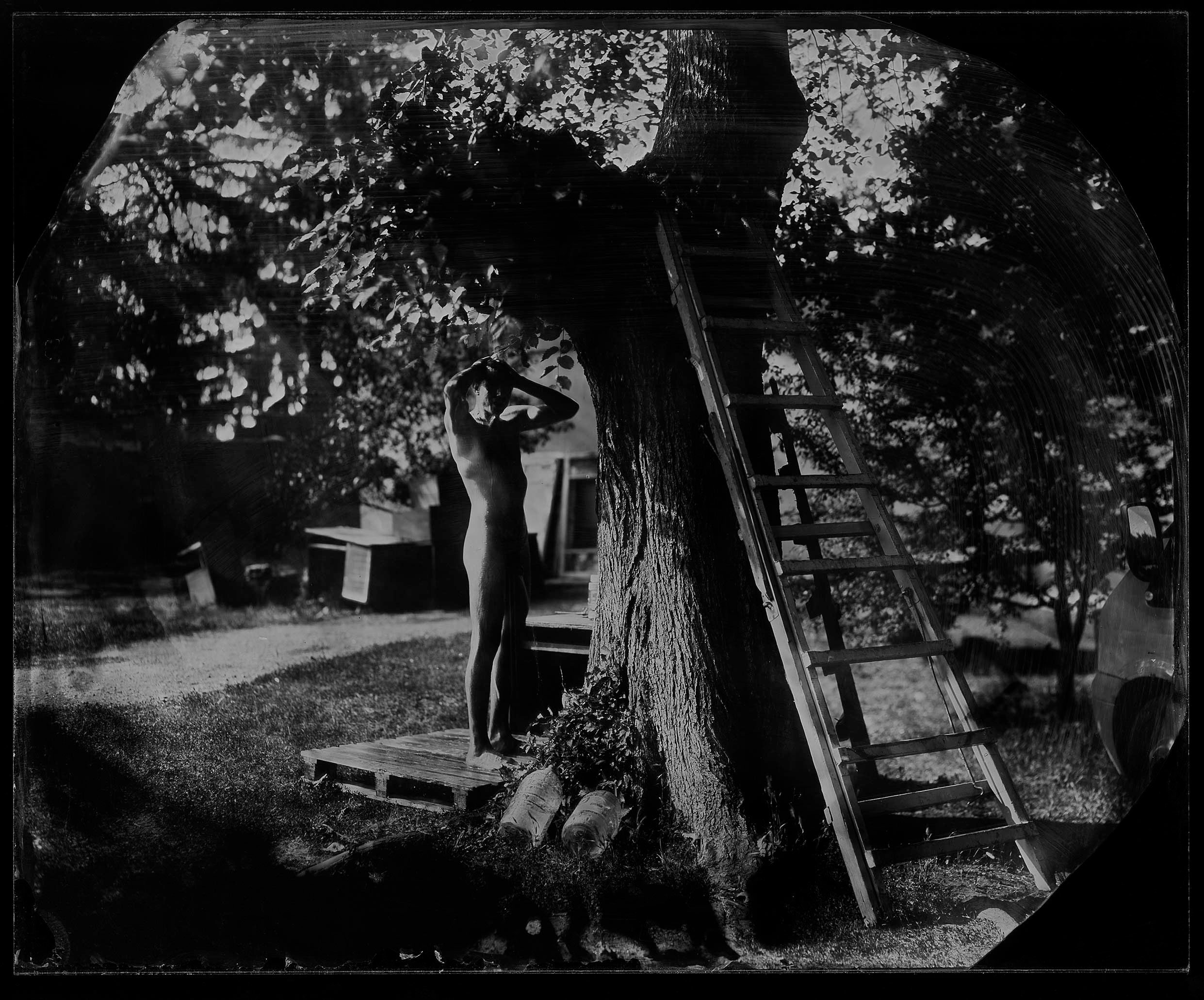

On his first trip, taking digital pictures, he realized he wanted to document this war using a mid-19th century photographic process. Kaprov became interested in the wet collodion process, or ambrotype, 6 years ago. Its complexity lies in the fact that it is necessary to apply a photosensitive material on a specially processed glass before the photograph itself, and after the exposure, immediately develop and fix the image on the glass. After development and fixation, an original positive image appears on the glass, which exists in a single copy and cannot be duplicated. A kind of Polaroid of the 19th century, in which the photographer himself applies the emulsion to the glass and develops it himself after shooting. It is difficult to use such a technique even in a studio with a prepared laboratory for processing ambrotypes. Not to mention the front line.

-

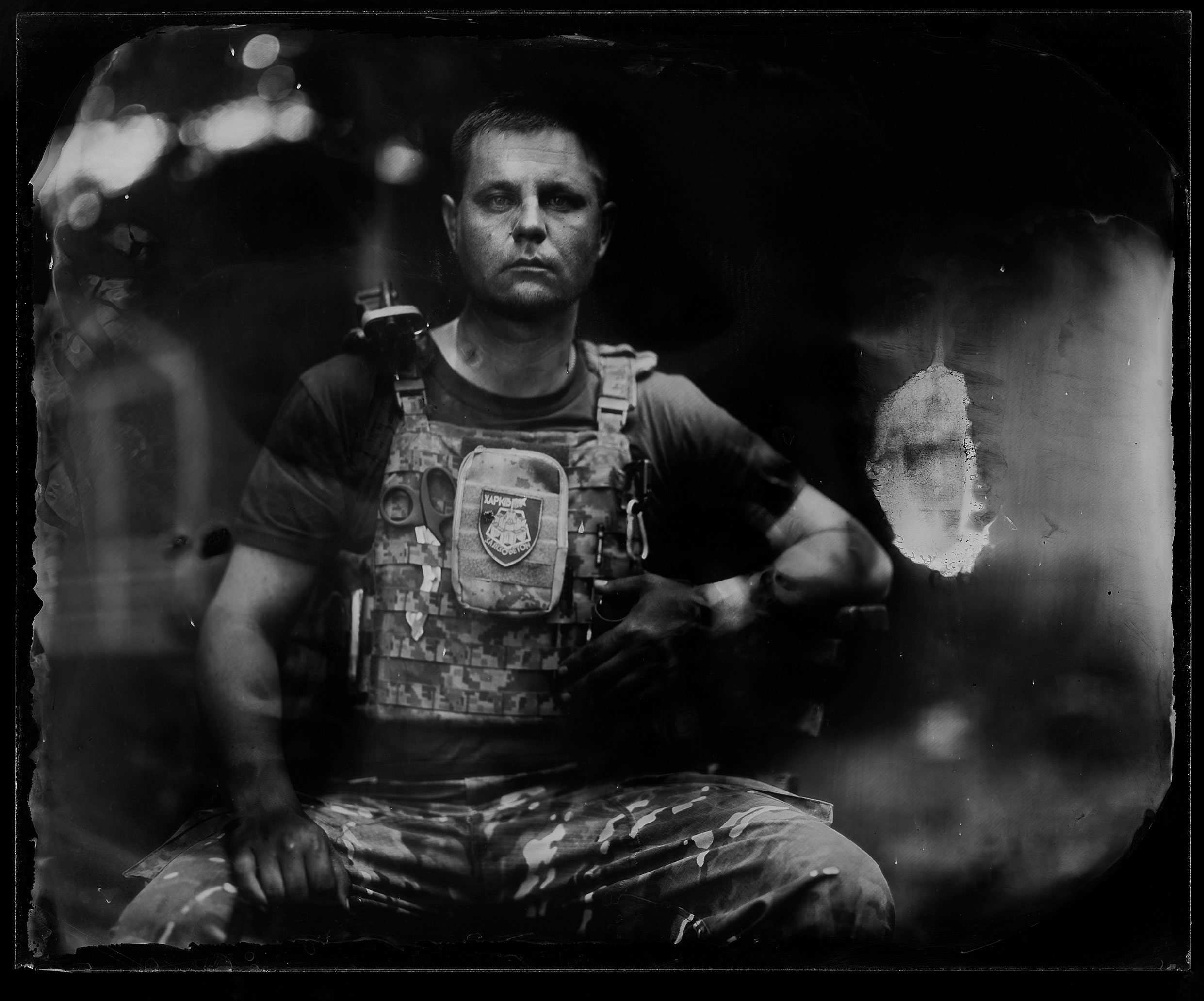

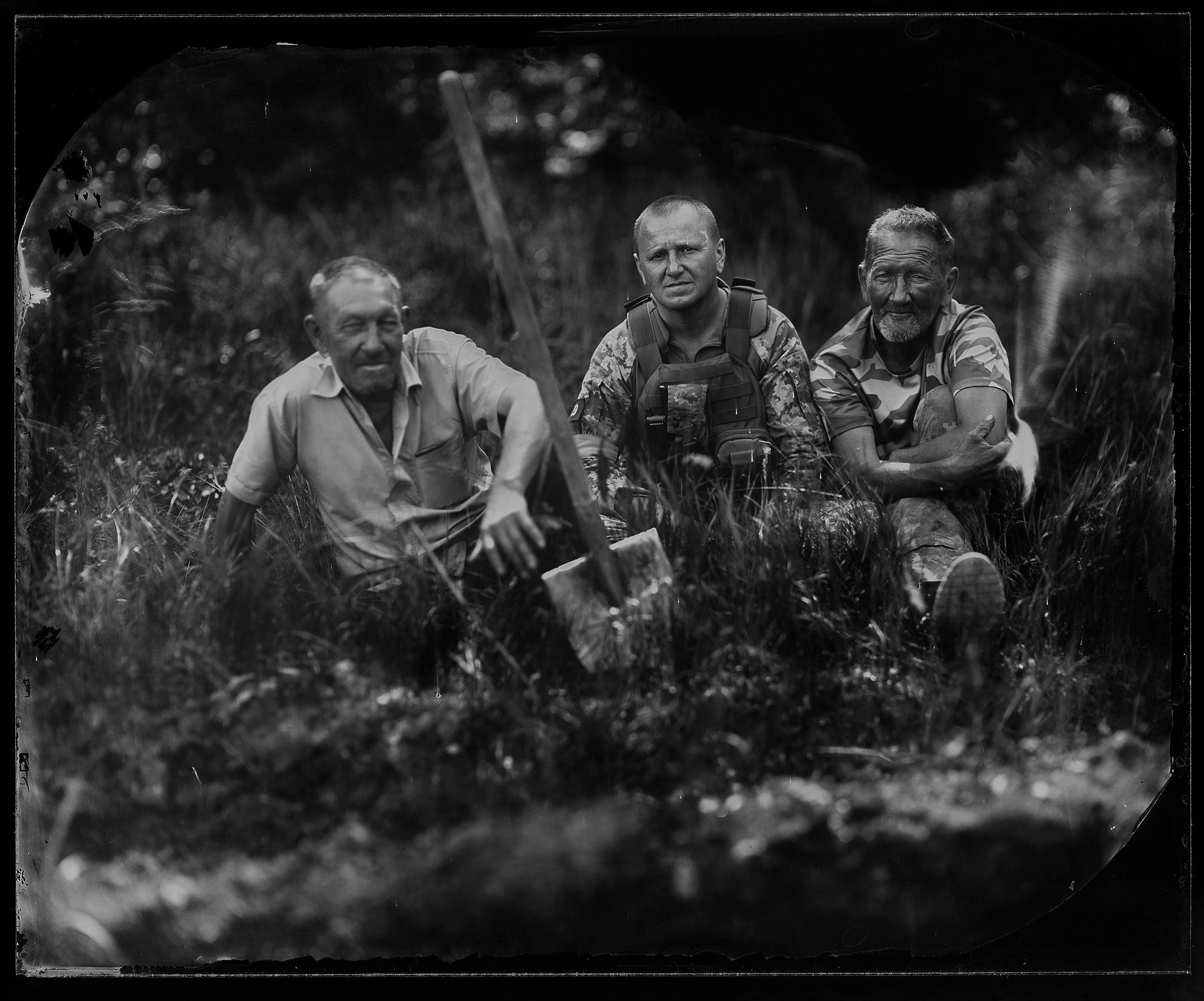

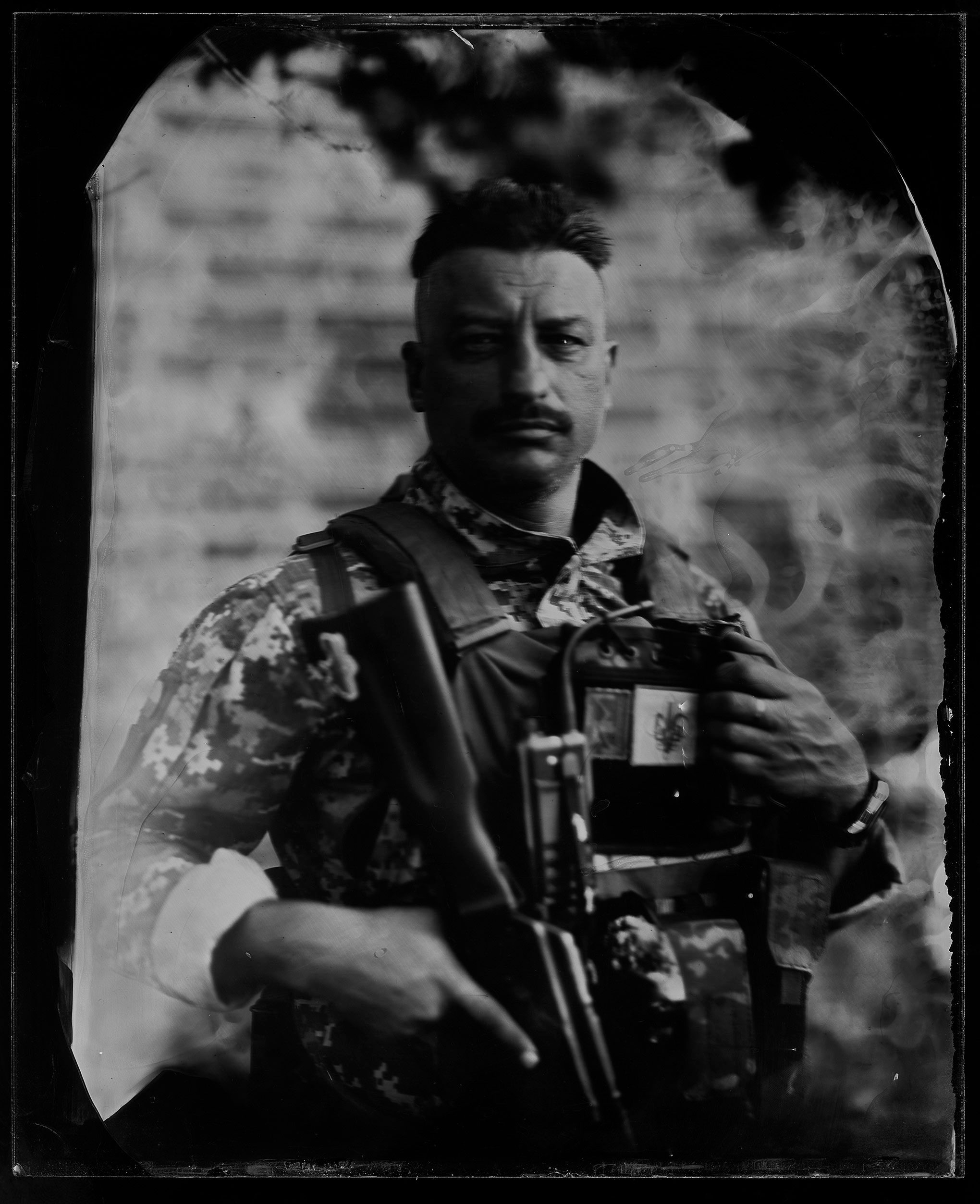

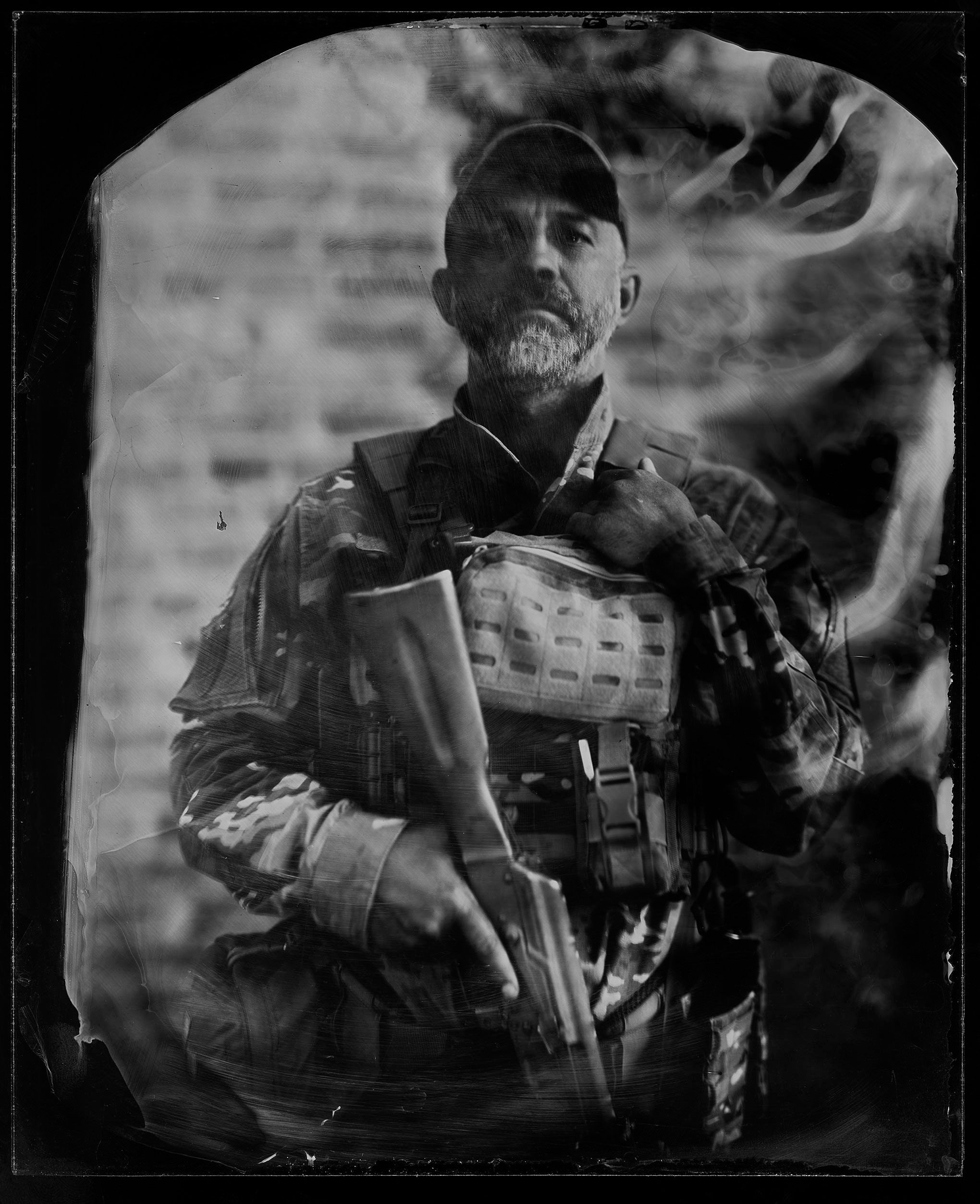

Photo: Eduard Kaprov -

Photo: Eduard Kaprov

-

Photo: Eduard Kaprov -

Photo: Eduard Kaprov

-

Photo: Eduard Kaprov -

Photo: Eduard Kaprov

In 1855, the Englishman Roger Fenton and his assistant Marcus Sparling arrived in Crimea in order to record military actions for the first time in history with the help of photography, namely using the collodion process. Despite a high temperature, several broken ribs, and cholera, Fenton managed to make over 350 usable large-format negatives.

-

Marcus Sparling sits on Roger Fenton’s photographic van, Crimea, 1855. Photo: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons -

The valley of the shadow of death, the road filled with cannonballs, Roger Fenton, Crimea, 1855. Photo: Library of Congress / Wikimedia Commons

“The work of Roger Fenton, above all, is striking in its dedication. It was very difficult to do what he did in the 19th century. To come from another continent to war. Bring so much photographic equipment and shoot. From a purely technical point of view, it was almost impossible to do this. This is a historical document that is forever imprinted in history. I also want to draw a historical parallel between what happened 167 years ago in Crimea and what is happening now. Thus showing that, unfortunately, the world has not changed. Everything is cyclical, nothing has changed. The form, weapons, and photographic techniques have changed, but the essence has remained the same. People continue to die while someone satisfies their political ambitions,” Kaprov says.

Eduard explains the choice of such a complex and expensive process by the fact that the world community, after more than three months of active military operations in Ukraine, is already tired of “direct” journalistic and documentary recording of events. He does not belittle the activities of journalists and documentarians at the front and treats their work with great respect. Kaprov sets himself completely different visual and semantic tasks than photographers engaged in “direct” photography. He says that his work should not be compared to documentaries, “it’s like comparing Bach to Dire Straits”. With his work, Kaprov hopes to draw attention to the war in Ukraine to a completely different audience than those who are usually interested in news.

-

Photo: Eduard Kaprov -

Photo: Eduard Kaprov

-

Photo: Eduard Kaprov -

Photo: Eduard Kaprov

After returning from Kharkiv with a lot of digital photos, Kaprov started a crowdfunding campaign to realize the idea. It is unlikely that he will be able to find a customer or an editor who could pay for such an expensive and risky project. It was the people who responded to Kaprov’s request: he managed to sell several of his works and collect funds for the implementation of his plan. “These people became my editorial office because they wanted to have their personal witness there.” With this money, Eduard bought a minibus in Germany, which he turned into a photo laboratory in Lviv, and stocked up on chemicals for creating ambrotypes and prepared glass for them. When everything was ready, he went to the front again.

Kaprov spent three weeks in the combat zone. He photographed civilians and military personnel in the Kharkiv region, and then went to Donbas and visited Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, and Lysychansk.

“I knew it would be a difficult mission. To set off on such a path alone, to solve issues along the way — from everyday problems with gas and purchases to negotiations with people and institutions in order to carry out the planned filming.”

During work, Eduard is maximally focused not on ruins, but on people. “I photographed a destroyed house on Saltivka only once,” says Kaprov. “The people I met, whom I filmed, treated what I was doing with respect and awe. They could not understand why I came from Israel, even for my own money, risking my life, to do this complex project. And I couldn’t find a clear answer… I could only say: “I feel this way and I can’t stay away.” They, for their part, trusted me and my fancy camera and were with me during those long seconds of exposure. They felt it was important for the history.”

-

Photo: Eduard Kaprov -

Photo: Eduard Kaprov

In three weeks at the front, Kaprov took about a hundred photographs, using half of the glass for ambrotype. He left his minibus with Kharkiv volunteers and returned to Israel to scan the footage and rest. After that, he is going to return to Ukraine and continue filming The Face of the Last War.

Photo: Eduard Kaprov