The G-Word: Why Genocide Will Keep Happening in the 21st Century (And Why the UN, as Always, Will Not Prevent It). Column of Daniel Lekhovitser

The war in Ukraine has proved once again that the bureaucratic structures of NATO and the United Nations are not able to the task of preventing wars and genocides. Zaborona editor Danyil Lekhovitser ponders why today’s security architecture is unprepared for such challenges, whether there will be genocide in the 21st century in Europe, and why the world community reacts too late.

Good people go to hell too

On April 6, 1994, Roméo Dallaire watched a CNN newscast in his bungalow in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, until a phone call rang out: a Rwandan government-owned Mystere Falcon plane had been shot down. President Juvénal Habyarimana had died. About two hours after Dallaire hung up, the most intense genocide, four times the speed of the Holocaust, would begin.

Last summer, General Dallaire, a NATO-trained military commander and former commander of the army’s peacekeeping brigade in Cambodia and Kosovo, received a call from the UN office. He was offered to become the head of the mission in Rwanda. The country’s political parties, through the help of Western countries, concluded the Arusha Accords, a reconciliation between the Hutu people and the Tutsi ethnic minority.

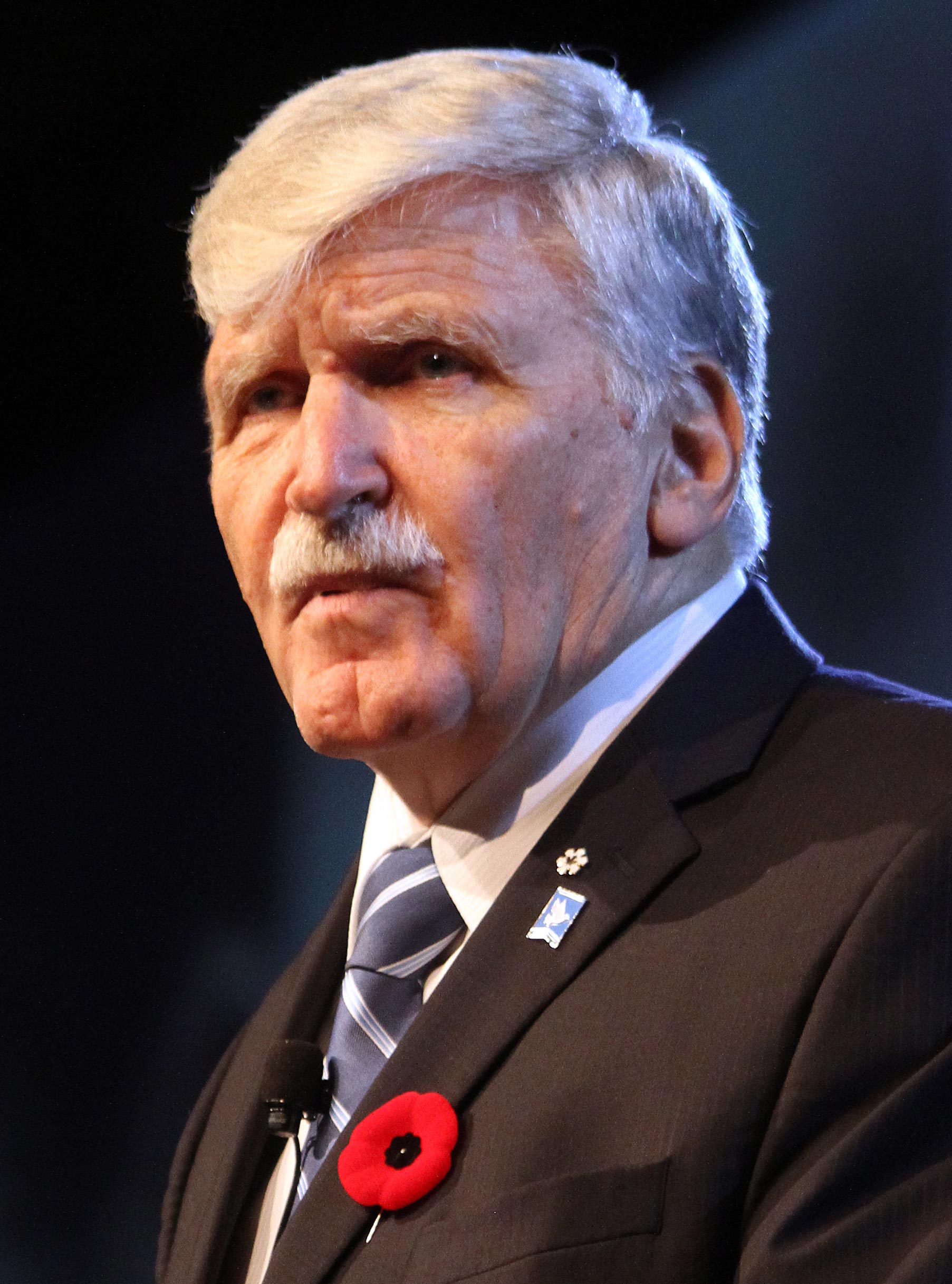

Roméo Dallaire Wikimedia

Hundreds of years of neighborliness between these people did not bear good fruit: during the colonization of Rwanda by the Belgians, the Tutsis were considered more Europeanized, so they got higher positions; after the country gained independence in 1962, the Hutus received more privileges. Periodically there were armed clashes of hatred between the peoples, but the 1992 Arusha Accords and the peacekeeping force were able to stop the bloodshed. Life in the country was getting better – so Dallaire agreed.

Before his plane took off in Kigali, a colleague of the general barely managed to take the booklet-encyclopedia about the political life and culture of Rwanda made for him. Daller and his colleagues knew absolutely nothing about the country.

***

That April evening in 1994, following the crash of President Habyarimana’s plane, power in Rwanda was seized by the military leadership of the Hutu. The gendarmerie and civilian Hutus will get machetes, secateurs, and kitchen knives from the cache. Local propaganda Radio Thousand Hills, which was calling for the killing of ethnic minorities in Rwanda for years, would announce Tutsis’ names, home addresses, and car numbers. About one thousand Tutsis would die in 20 minutes. About 8 thousand would die in one day.

A child lies on a stretcher May 25, 1994 in Rwanda. Following the assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimana in April, 1994 genocide of unprecedented swiftness left up to one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus dead at the hands of organized bands of militia by early July, 1994. Photo: Scott Peterson / Liaison

In January 1994, three months before the genocide began, Dallaire was contacted by a high-ranking Rwandan government official who introduced himself as Jean-Pierre. He warned that the Hutus were buying huge quantities of cold steel. General Dallaire would send a telegram to the UN headquarters in New York asking for permission to search the warehouses of the Hutus, where weapons can be stored. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan banned the search, citing the provocative nature of the operation.

The UN and the administration of President Bill Clinton were warned about the possibility of genocide by the International Commission on Human Rights to no avail. During the three months of genocide in Rwanda, the US president had never convened an emergency foreign policy meeting. If America and the United Nations play the role of the global 911 service, the line is either busy or no one wants to pick up the phone.

A United Nations soldier distributes gum to children April 13, 1994 in Kigali, Rwanda. Following the apparent assassination of Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana, a massive wave of Hutu-inflicted revenge killings has rocked the African nation, leaving thousands of Tutsi civilians dead and renewing the civil war between the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front and the Hutu-backed government. Photo: Scott Peterson / Liaison

Dallaire commanded 2,500 poorly armed soldiers: he had quarreled many times with officials from New York and Washington, calling for replenishing his soldiers to more than 5,000 troops and providing better weapons. The troops and gendarmerie of Rwanda, as well as civilian Hutus armed with machetes, outnumbered the peacekeeping mission soldiers.

The Belgian soldiers who guarded about 2,000 Tutsis at the Ecole school were first surrenderers. Armed Hutus sat on the car trunks ten meters away from the school, drinking beer and shouting “Pawa, Pawa”, a racist shout about the dominance of the Hutu people. On 19 April 1994, Belgium instructed soldiers to leave the country. Mothers and children clung to the doors of the soldiers’ departing cars. They were repelled by weapon butts. The next day, almost all 2,000 Tutsis were found dead. Dallaire was left without 400 soldiers from Belgium.

5,000 people seeking refuge in this house of God were killed by grenade, machete, rifle and burning alive. Most of it has been moved into another building, but among the pews remains jawbones, leg bones, children’s shoes, hairpicks, scarves and more. We walked through it up to the front row. It was overwhelming. Notice the Stations of the Cross on the wall overlooking everything. Photo: Scott Chacon / Wikimedia

Diplomats and embassy staff had left Rwanda. Dallaire was advised to save the Americans and his soldiers. He proposed to mobilize peacekeepers from nearby African countries to evacuate the Tutsis from Kigali, the capital of Rwanda which had been taken into the siege by Hutu troops. The general had been offered the opposite: try to transport thousands of Tutsis to the airport, from where they can be taken to a safe place. The road to the airport is about tens of kilometers, there were many checkpoints set up by the Hutus. Soon the connection disappeared, only the satellite phone was working. Dallaire and his men decided to guard the Tutsis that had gathered at the Hôtel des Mille Collines and Amohoro Stadium. They saved thousands of lives.

Refugees who flew raging battles in Kigali live in a makeshift camp near the road leading to the Tanzanian border 12 May 1994. Thousands of refugees have been fleeing Rwanda’s ethnic slaughter where an estimated 200,000 people have died in a civil war between the Tutsi minority and the majority Hutu tribes. Photo: GERARD JULIEN / Getty Images

Three months later, the Clinton administration agreed to Dallaire’s plan and deployed troops when the genocide was over. According to various estimates, between 800,000 and a million Tutsis fell victim to it. Bill Clinton later accused his advisers of negligence, as they had not drawn his attention to the problem of the third-world countries. This was not surprising: Secretary of State Warren Christopher himself could not find Rwanda on the map without the help of an atlas, and Clinton’s staff confused the names of the Rwandans: Tutu and Hutsi? Or Hutu and Tutsi?

A child’s eye is bandaged May 25, 1994 in Rwanda. Following the assassination of President Juvenal Habyarimana in April, 1994 genocide of unprecedented swiftness left up to one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus dead at the hands of organized bands of militia by early July, 1994. Photo: Scott Peterson / Liaison

In 2005, Dallaire became a senator in Canada. Before that, he tried to commit suicide. In his memoirs, he blamed himself for not doing enough. Although he has done more than all countries and international organizations together.

Having time to leave first

Roméo Dallaire’s mission is probably one of the most cinematic examples of courage and humanity that fits well a Hollywood script. This is a special case. Instead, indecision or outright cowardice of international and military organizations are systemic. Just recall the protection by Dutch NATO soldiers of the Serb-besieged city of Kosovo, where Croats and Bosniaks were hiding. After the clash with the Serbs, the peacekeeping contingent, which requested air support to be refused, was ordered to leave the city so as not to “provoke” the Serbs. As a result, Srebrenica has become a toponym-pit, only a reminder of the number – 8,000 civilians killed – because the solid currency of human suffering is considered in numbers. They embellish the headlines, they are shocking, they are quickly forgotten.

Refugees arriving in Tuzla after escaping from Srebrenica, where between 6000 and 7000 of their fellow moslems were murdered by Serbian forces Photo: Pictures Ltd./Getty Images

We can continue mentioning failed peacekeeping missions in Mali, Somalia. More interestingly, at the time of the outbreak of interethnic conflicts, the UN and the participating countries order to evacuate Europeans, Americans, diplomats, ambassadors and only, last and least, to protect those who, according to the UN rules, must be protected. The problem, of course, is in the salvatory and at the same time murderous hierarchy. And there is a bigger issue – after the evacuation no one returns to help those who were forced to stay.

A Bosnian child sports oversized shoes as he walks in a street of Sarajevo under the protection of an armored personnel carrier 12 July. UN officials in Bosnia faced a humanitarian crisis in the eastern enclave of Srebrenica as Serb separatists pressed their advantage and the UN Security Council struggled to respond to the fall of the former safe area. Photo: JOEL ROBINE / AFP via Getty Images

Even in cases of evacuation, it is necessary to honor the traditions. There is a diplomatic decorum: an ambassador leaves a war-torn country in the last car as if defending the diplomats riding ahead him. The news likes to announce this proudly. They do not like to report that the ambassador may be the last in convoy but among the first to leave.

The G-word

Governments around the world do not like the word “genocide.” It should not be mentioned in speech, it should not be used in conversations with journalists. The Trump administration did not call the Rohingya genocide perpetrated by the Myanmar military junta as the genocide. If journalists are putting pressure on you, there are half-measures: the term “ethnic cleansing”, which was used, for example, by Trump’s secretary Mike Pompeo, when the victims of Myanmar numbered in the thousands. The government’s mention of genocide, or g-word, as politicians call it, is problematic. A loud word requires loud action.

Rohingya Muslim refugees shelter in cement pipes at Kutupalong refugee camp in the Bangladeshi district of Ukhia on September 20, 2017. – Bangladesh’s army was ordered September 20 to take a bigger role helping hundreds of thousands of Rohingya who have fled violence in Myanmar, amid warnings it could take six months to register the new refugees. Troops would be deployed immediately in Cox’s Bazar near the border where more than 420,000 Rohingya Muslims have arrived since August 25, said Obaidul Quader, a senior minister and deputy head of the ruling Awami League party. Photo: DOMINIQUE FAGET / Getty Images

When it comes to the legal field, declaring genocide requires adhering to the 1948 Genocide Convention: exerting political pressure, imposing economic sanctions, and supplying ethnic minority troops with weapons . In addition, after the declaration of genocide, trading companies are usually forced to leave the genocide-commencing country. The term “ethnic cleansing” does not oblige them to do so, they can do business as usual. Most often, a “war” is prefered to ethnic cleansing. It is more convenient and somehow more habitual to condemn war. Thus, it is wrong for a third countryto take part in it.

In many ways, it is liberal values that help goverments do nothing. The principle of non-interference allows them to observe and express concern. Freedom of speech does not allow one to influence hate media that directly call for genocide. In the case of the Rwandan Radio of a Thousand Hills, at several UN meetings, participants suggested jamming the signal or breaking the antenna, although they considered this a violation of freedom of speech, while several thousand Tutsis died per day.

The so-called consolidated West takes several months to declare the massacre a genocide, and the same amount of time to do something. These two reactions are, of course, related. The longer you hide this word from yourself in the back rooms of the mind, the longer the saving inaction lasts. When Jan Karski, a member of the Polish resistance movement, dressed up as a German soldier in 1942 and visited the Warsaw Ghetto to meet President Roosevelt in person a year later and talk about concentration camps and the Holocaust, no one in the United States believed him. Or he was believed, but they did not want to do anything.

There is something almost fantasy, fictional about genocide, as observer countries see it; probably that’s why it’s so hard to believe in it. Genocide is psychotic, irrational, so it’s hard to imagine that it’s even possible. It seems that this is why there are always so many conspiracy theories surrounding genocide – the unwillingness to believe (there is a more accurate English word ‘to comprehend’ – as if gaining difficult knowledge against fear and resistance) is easily displaced by conspiracy theory. Serbs claim that Srebrenica never took place and that photos of those killed were staged by NATO; Boris Johnson’s conversation with Myanmar politicians in 2018, who claimed that the Rohingya set fire to their own homes and themselves with them; finally, Ukrainians who bomb themselves.

Muslim women pray at the mass funeral for 613 newly-identified victims of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre attended by tens of thousands of mourners at the Potocari cemetery and memorial near Srebrenica on July 11, 2011 in Potocari, Bosnia and Herzegovina. At least 8,300 Bosnian Muslim men and boys who had sought safe heaven at the U.N.-protected enclave at Srebrenica were killed by members of the Bosnian Serb army under the leadership of General Ratko Mladic, who is currently facing charges of war crimes in The Hague, during the Bosnian war in 1995. A Dutch court recently found the Dutch government responsible for the deaths of three of the victims when Dutch U.N. peacekeepers handed over the three men, who had been working on the Dutch base in Srebrenica, to Serbian soldiers. Photo: Sean Gallup / Getty Images

Always remember/forget

In the same English – in a language more sensitive to the description of disasters – there is an expression ‘to bear a witness’. It is to carry – like a cross, a burden, overwhelming with its weight. Being a witness, even indirectly, by looking at a Facebook-blurred photo of mass graves and people being shot is an unbearably difficult, often lonely job. And few are willing to take it.

Winfried Georg Sebald, a German-English writer who has devoted almost all of his novels to the memory of the Holocaust, or rather the memorylessness of it, wrote about how people push disasters to oblivion. About those who pretend that instead of World War II and the Holocaust there was a white gap, an empty nothing, and not pits with bodies. Perhaps we are living again in one of his stories, in which the global community pretends that there is no genocide. Journalist David Rohde, who covered the events in Srebrenica, wrote that the very denial of genocide and disunity over the prevention of human catastrophes leads us to solve new ones. One of his articles ends with a reference to the events of 20 years ago – when Russia’s representative to the UN (at the time it was Vitaly Churkin) denied the genocide of Croats. “The most important, he writes, lesson of Srebrenica is that half-measures can do far more harm than good. And Russia’s veto suggests that more division and half measures are likely to come”. As we can see, he was right, and those who willingly deny crimes against humanity are more likely to plan their own.