At the end of December, Zaborona’s editors received a document from the National Policy Institute, a public research organization. The document was a dossier on far right political figure Sergei Korotkikh, also known by the nicknames “Malyuta” and “Boatswain.” Korotkikh studied at the Belarusian KGB Institute, fought in Chechnya, and is friends with another well-known Russian neo-Nazi, Maxim “The Hatchet” Martsinkevich. The wife of Yaroslav Babich, lawyer and ideologist for the Azov Battalion, who died under suspicious circumstances, believes that it was Korotkikh who killed her husband. One of the dossier’s authors was recently abducted and severely beaten, and is now claiming that his attackers were sent by Korotkikh. On January 8, the authors published a statement. Zaborona reports on its most important points.

Warning: this article describes acts of violence.

Sergei “Boatswain” Korotkikh, the ex-commander of the Azov Battalion’s reconnaissance regiment, is widely feared among other Ukrainian right-wing radicals. Zaborona’s sources, people associated with Azov and the paramilitary organization National Militias, try to avoid talking about him, calling it “dangerous to their health.” And they have good reason to fear him: Sergei Korotkikh’s biography is closely intertwined with the Belarusian KGB, the Russian FSB, murders, kidnappings, and big money.

One of the dossier’s authors is Ivan Beletsky, a lawyer and public figure who co- founded the Institute for National Policy. After experiencing political persecution in Russia, he fled to Ukraine, where he was granted asylum. Beletsky was one of the organizers of the far-right “Russian March” protests, and is a co-founder of the anti- Putin Artillery movement.

On December 28, 2020, Beletsky was kidnapped and severely beaten near Kyiv.

“For the last three months, I’ve been receiving threats from Korotkikh’s men,” he told Zaborona. “Around the same time, we started actively compiling the dossier on Sergei. They tracked my connections in Russia, my past, my closed businesses. We were terrified they would catch us at home. Or dig my mother up [from her grave – she died long ago],” he explained

On December 28, he decided to meet with his pursuers in a crowded place. They chose a supermarket off of a highway. But when Ivan arrived, no one came to meet him, so he waited a few minutes before deciding to call a taxi. “For some reason, my Uber app stopped working, and suddenly a silver car with an “Uklon” [a Ukrainian ridesharing app] sticker pulled up. I was glad and I hopped in. An athletic-looking guy was sitting next to the driver. I asked who he was, and the driver said he was just another rideshare passenger with a different address. I was confused — I wasn’t expecting that.” They took Ivan to the middle of nowhere on Sofievskaya Borschagovka and beat him up. When he came to his senses, the car and the attackers were gone. Ivan went out onto the road, where people called an ambulance and the police. He was diagnosed with a fractured jaw, numerous hematomas, and abrasions.

Zaborona has obtained Beletsky’s medical report.

“When they were threatening me, back before the kidnapping, they said that they had raised my case in Russia in 2009,” Ivan Beletsky told Zaborona. “And they knew it in detail. Where did they get access to information kept in the Russian Investigative Committee and FSB offices? Our report has the answer to this suspicious detail.”

We tried to meet with Sergei Korotkikh in order to confirm some of the dossier’s statements and give him a chance to defend himself. Korotkikh declined to speak, but Zaborona’s offer remains open should he want a platform to express his position in the future.

KGB school

Sergei Arkadievich Korotkikh was born in Togliatti, Russia, but later moved with his parents to Belarus. From 1992 to 1994, he served in the Russian army’s Recon Battalion. According to Sergei himself, he enjoyed books and films about spies ever since he was a child. Romantic myths and a thirst for knowledge spurred Korotkikh to enroll in KGB school after leaving the army. He studied there for two years before being expelled in 1996. In Korotkikh’s own telling, this was a result of clashes with the police during the “Chernobyl Way” march, which was organized by the Belarusian Popular Front opposition party.

None of the sources Zaborona spoke with from the Belarusian Popular Front remember Sergei at the march. Members of the Belarusian opposition do know Korotkikh from a different case, however: in 1999, three critics of the Lukashenko regime, Andrei Sannikov, Dmitry Bondarenko, and Oleg Bybenin, were assaulted by members of the Belarusian branch of the far right organization Russian National Unity (RNU). One of the attackers was Sergei Korotkikh.

Sergei wrote that incident off as “a regular fight between subcultures.” But the victims claimed the attack had been organized by Belarusian intelligence agencies. Researchers of the far right suspected RNU of working closely with Russian and Belarusian intelligence services, and one of the leaders of the organization, former officer of the Almaz special forces unit Valery Ignatovich, has been called a fighter for Alexander Lukashenko’s “death squad” by journalists.

According to the dossier’s authors, Sergei Korotkikh wasn’t kicked out of the KGB; on the contrary, he may have been recruited by them to join Belarus’s radical right-wing environment in order to collect information and fight opposition to the Lukashenka regime.

The richest neo-Nazi organization in Russia

After RNU’s defeat in Belarus, Sergei Korotkikh ended up in Russia. In 2004, he founded the far-right National Socialist Society along with one of the assistants of Dmitry Rumyantsev, deputy from the Liberal Democratic Party in the State Duma. According to Russian the publication The Insider, the organization “bizarrely combined open worship of Hitler with sympathy for Vladimir Putin.” The NSO lauded the scientific, technical and cultural achievements of Hitler’s Germany, training soldiers for an upcoming “race war.” Sergei Korotkikh served as the organization’s combat instructor, in addition to managing the NSO’s finances. He even paid salaries to Rumyantsev and the militants “from his own pockets.”

As Russian newspaper Izvestia wrote, the NSO was “one of the most influential and wealthy neo-Nazi organizations in Russia.” At the time of the arrest of its members in 2010, 200 million rubles were found in the accounts of the organization’s management, and almost1.5 billion rubles allegedly passed through NSO banking structures, which at that time amounted to $55 million.One of the NSO’s main sponsors was Maxim Gritsai, who made money from tax schemes involving people with disabilities and wire transfers. The NSO members’ passports were connected to bank cards, which received large transfers of money from unknown sources. The members would withdraw money from the cards, give it to Gritsai’s people, and receive a reward, then “donate” up to 30% of it to the NSO. “We were engaged in various activities, in particular cashing out money,” Korotkikh himself said in an interview. Maxim Gritsai also provided the NSO with an office and a gym, and supported the organization’s candidates in municipal elections.

The co-founder of the organization, Dmitry Rumyantsev, had powerful patrons: his brother Oleg, a lawyer, was one of the original drafters of the Russian Constitution and an author of the treaty between Russia and Belarus. He has a close relationship with the Putin administration. Dmitry Rumyantsev himself has repeatedly told reporters that he has friends among the Russian security forces.

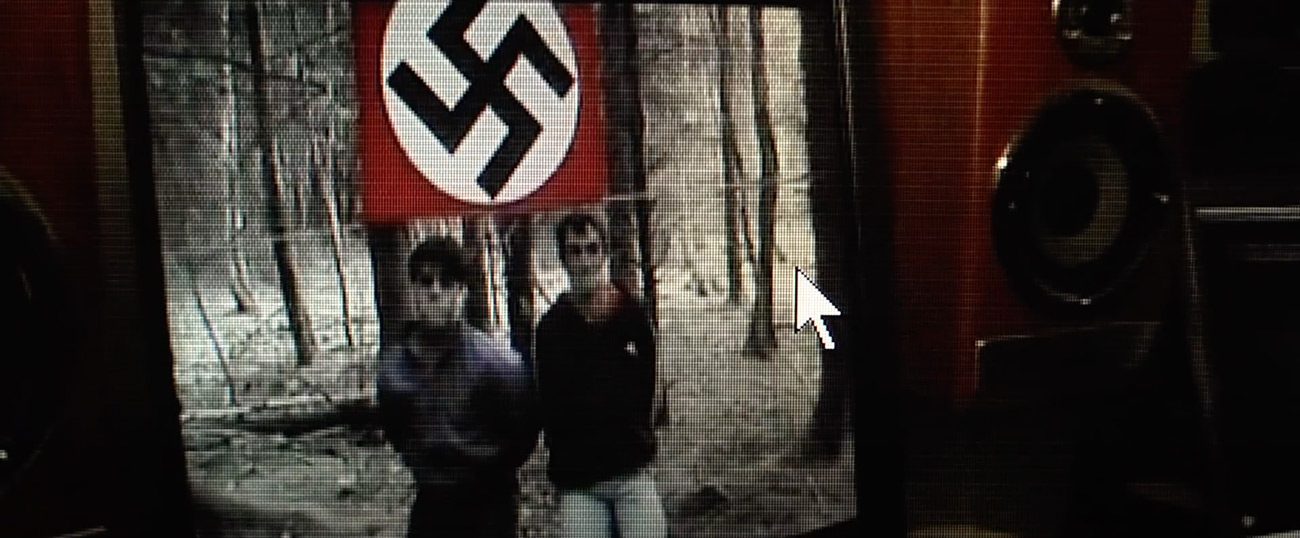

“Execution of a Dag and a Tajik”

On August 12, 2007, a video titled “Execution of a Dag and a Tajik” appeared on the Internet. In the video, two tied-up men say to the camera that they’ve been “arrested by Russian National Socialists,” then several unknown persons in balaclavas cut off one prisoner’s head with a knife and kill the other with a shot in the back of the head, all in front of a flag with a swastika. The killers identify themselves as members of the National Socialist Party of Russia (NSPR).

At first, Russian law enforcement declared the video to be staged. They later acknowledged it as real, even reporting on the arrest of the murder suspects, but eventually the brakes were put on the case.

Then Israeli film director Vladi Antonevich conducted his own investigation. Posing as an American journalist, Antonevich spent years among Russian neo-Nazis. He presented his version of events in a documentary film titled Credit for Murder, released in 2015. After talking with Russian neo-Nazis and thoroughly examining the footage, Antonevich came to the conclusion that the video of the execution was filmed by the leader of the group Format-18, Maxim “The Hatchet” Martsinkevich. Both murders were carried out by Sergei Korotkikh while Dmitry Rumyantsev, leader of the NSO, watched.

Antonevich emphasized that the double murder was different from other nationalist attacks in that it “was thought out from start to finish.” Moreover, according to Antonevich, it was not Martsinkevich, Korotkikh and Rumyantsev who planned it, but people “in other offices” somewhere. Antonevich claims those people wanted to “put [Rumyantsev] on the hook” by having him carry out the execution.

The director found out the exact date of the disappearance of Shamil Udamanov, one of the victims. This happened on April 4, and not in the middle of summer, as the Russian media mistakenly wrote. The date contradicts a rather popular argument of Martsinkevich’s supporters, who claim that “The Hatcher” couldn’t have participated in the murder because he was in prison at the time. According to Udamanov’s father, he disappeared about three months before Martsinkevich was arrested in Moscow on July 2.

The Vanguard

Two days after the video was published in 2007, an unknown person sent an email to the editorial office of the Chechen separatist news site Kavkaz Center. It said that the nationalists were declaring “armed war against black colonists” and were planning to “evict all Caucasians and Asians from the Russian territory.” They also demanded the release of other nationalists, an end to the persecution of Maksim Martsinkevich, who had been arrested by the Russian security forces on July 2 of the same year, and the dismissal of Vladimir Putin. The radicals wanted to transfer power in Russia to the National Socialist government, “which should be formed by the leader of the National Socialist Society of Russia, Dmitry Rumyantsev.” They called themselves the fighting wing of this organization, acting independently, as well as the “vanguards” of the National Socialist struggle. The text was written in perfect Russian, except for a typo in the word “vanguard.” They used the Belarusian spelling.

A few months after the video was published, Sergei Korotkikh was expelled from the NSO for “financial abuse” and “inciting hatred within the organization.” In April 2008, Dmitry Rumyantsev also left, and the video “Execution of a Dag and a Tajik” became a call to action for neo-Nazis in Russia: a wave of hate-motivated killings swept across the country. In 2010, the Russian Supreme Court banned NSO activity within the territory of Russia, labeling it an extremist organization. Russian security forces began detaining members of the FNL; many of them received prison terms. But the founders, Korotkikh and Rumyantsev, were not prosecuted, and Maxim Gritsai was not officially implicated in the case as a sponsor of an extremist group.

On September 16, 2020, the leader of Format-18, Martsinkevich, was found dead in the Chelyabinsk pre-trial detention center. According to the official version of events, he committed suicide. Representatives of the Russian Investigative Committee claimed that shortly before his death, Martsinkevich had confessed to the double murder of “persons of non-Slavic nationality” in 2007. According to a source who spoke to Kommersant, the investigation suggested that Sergei Korotkikh could also be involved in the murder, but he is not wanted or suspected publicly.

Surkov’s controlled nationalism

According to the dossier authors and film director Vladi Antonevich, the order for the high-profile murder came from the Kremlin. The initiator of the murder could have been Vladislav Surkov, Vladimir Putin’s assistant at the time, who was involved in Russian nationalist movements and parties. In their version of events, Sergei Korotkikh is an FSB agent who was thrown into the Russian neo-Nazi environment, just like when he worked in the Belarusian branch of the RNU. “The KGB of Belarus and the FSB of the Russian Federation work closely together and have various cooperation agreements, in particular within the framework of the CIS and the CSTO and other informal agreements, and transfer residents to each other,” the authors said. Korotkikh, in their opinion, was tasked with creating an extremist organization, the NSO, and organizing a double murder. The crime-triggered wave of violence intimidated the Russian population ahead of the presidential elections, and its curtail increased the credibility of the authorities, who detained neo-Nazis and organized show trials.

In February 2013, Korotkikh, together with Martsinkevich, who served 3 years in a Russian prison, fought with anti-fascists in Minsk. They doused Martinkevich with urine, he responded with a gas pistol, and Korotkikh inflicted several knife wounds on one of the attackers. Both were detained and released ten days later.

Korotkikh in Ukraine

In 2014, Korotkikh arrived in Ukraine, where he served in the war in Donbass as a scout in an Azov regiment. At the time, the battalion was largely composed of members of right-wing radical organizations from Left-Bank Ukraine, as well as football fans. Over time, Azov was reorganized and integrated into the National Guard, which is part of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

In December 2014, Sergei Korotkikh was given Ukrainian citizenship, and Petro Poroshenko thanked him for his service during the ceremony. Korotkikh looked more like the exception than the rule, given the fifth president’s strict citizenship policy.

Having received a passport, Korotkikh forged a career in the National Police; in May 2015, he became head of the newly created Police Department for the Protection of Strategic Objects, where he worked until 2017. According to his 2015 declaration, Sergei Korotkikh had a total of almost a million dollars; he bought himself two apartments in Kyiv and an L-39 Albatross combat trainer. Korotkikh also maintains a friendly relationship with Interior Minister Arsen Avakov’s son Alexander. This was confirmed by Korotkikh in an interview.

Sailor’s knot

On July 26, 2015, Yaroslav Babich, lawyer and ideologist for the Azov battalion, was found dead in his apartment. He had been hanged on a wall bar in front of large portraits of his three children. According to the investigation’s official version, he died by suicide, but his widow, Larisa Babich, and former well-known Azov representative Oleg Odnorozhenko believe Babich was murdered by Korotkikh.

According to Larisa Babich, the impetus for the murder was a financial issue among Azov leadership. She’s confident that the likely murderers of her husband decided to fake his suicide this way for a reason. On one hand, the attackers hoped to discredit an honest and respected public activist; the coroner claimed that Yaroslav had been engaged in “scarfing” (a type of autoerotic asphyxiation) in front of portraits of his own children. On the other hand, they wanted to make sure that Babich’s relatives wouldn’t attempt to establish the truth, in order to avoid public disgrace.

The sailor’s knots on Babich’s rope support this version of events — according to Korotkikh himself, he’s interested in yacht building. Additionally, “boatswain” is the name of a position on ships. Korotkikh adopted this nickname when he first moved to Ukraine. Sergei Korovin, another Azov leader whose nickname is “Horst,” is alleged to have been Korotkikh’s accomplice.

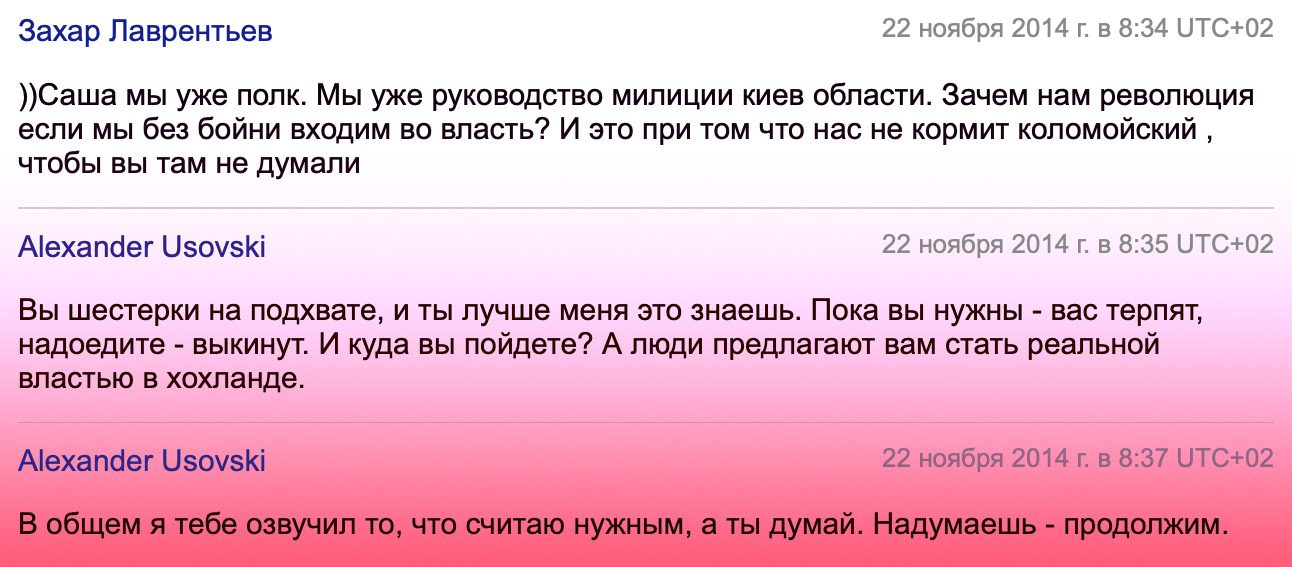

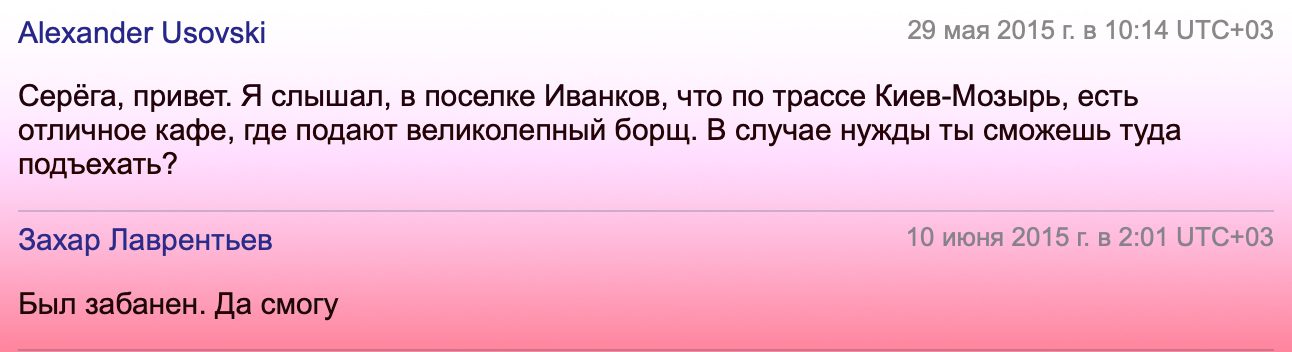

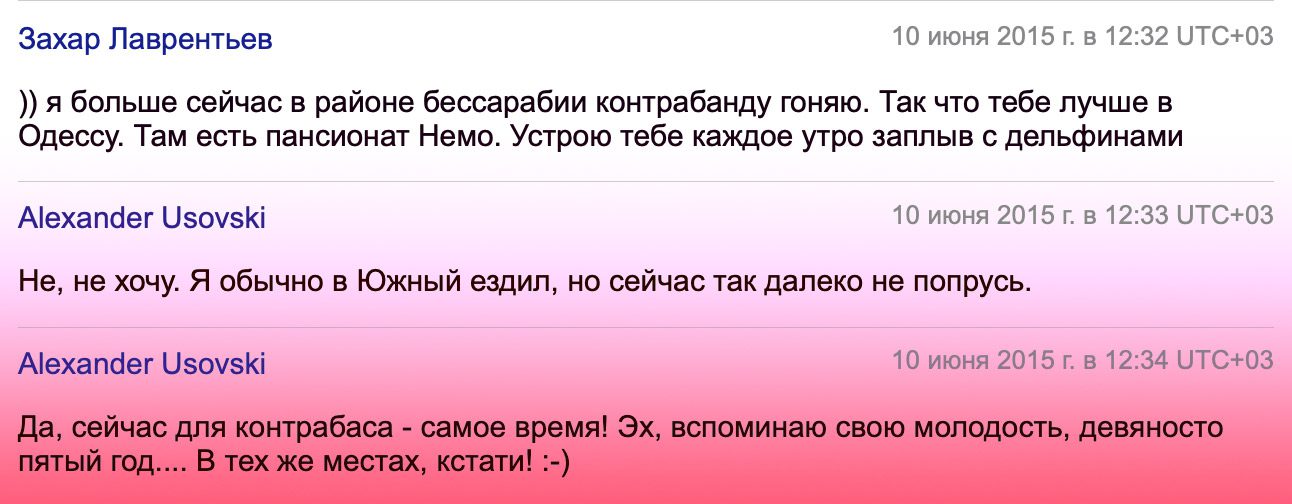

Zakhar Lavrentiev and Denis

In February-March 2017, the Ukrainian Cyber Alliance published letters from Belarusian citizen Alexander Usovsky, an alleged FSB agent and organizer of pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian demonstrations in Eastern Europe. Hacktivists, in particular, leaked his November 2014 Facebook correspondence with Sergei Korotkikh, who kept an account under the pseudonym “Zakhar Lavrentiev.” Usovsky suggested carrying out a new coup d’état, but Korotkikh refused: “Sasha, we are already a regiment. We are already the leadership of the militia of the Kyiv region. Why do we need a revolution if we’re coming into power without slaughter?” he wrote. “I’m driving more contraband into the Bessarabia region right now.” In a later interview, Korotkikh claimed to have been referring to the fight against contraband, rather than contraband itself. In June 2015, Usovsky suddenly suggested that he and Lavrentiev meet on Ukrainian territory, and Korotkikh agreed.

“[The Russian leadership] constantly makes mistakes. They invested in Tyagnibok, and that was a dead project, they thought and walked around Yarosh, and I told Denis in May that he was a soap bubble and was right,” Korotkikh wrote to Usovsky. In total, the name “Denis” appeared 885 times in Usovsky’s messages with various people. This name almost always appeared next to the surname “Loginov,” which is mentioned 786 times.

Denis Loginov previously headed the interregional branch of the “Restrukt” movement, which was created by neo-Nazi Maxim “The Hacker” Martsinkevich. Several members of Restrukt told the Russian newspaper Meduza that after the trial, they learned that Loginov worked at the Center for Combating Extremism, and that his father Andrei is the Deputy Chief of Staff of the Russian government, and is responsible for supporting legislative activity.

According to unnamed sources who spoke to the dossier’s authors, Loginov helped Korotkikh transport Russian neo-Nazis from the Russian Federation to Ukrainian territory to participate in hostilities on the side of the Azov battalion. The authors suggest that the Kremlin was interested in the presence of Russian right-wing radicals on the side of Ukraine during the active phase of military aggression in order to use it for propaganda purposes.

Svinarchuks

On March 16, 2019, the eve of the presidential elections, the paramilitary organization National Militias, which is associated with Sergei Korotkikh, held a “Day of Anger” protest near the presidential administration building in Kyiv. They demanded that Petro Poroshenko send ex-NSDC secretary Oleg Gladkovsky and his son Igor to jail as the main defendants in the investigation into the theft of the Ukrainian defense industry. The National Forces came to the house of Igor Gladkovsky several times, in addition to pursuing Petro Poroshenko during his election tour in Zhitomir, Poltava and Cherkassy. Korotkikh himself appeared on television, where he actively criticized the then-president and the SBU.

Based on a good deal of evidence, Zaborona then suggested that the National Militia, subordinate to the political party of the creator of the Azov regiment, Andrei Biletsky, the National Corps, were fulfilling the political orders of Interior Minister Arsen Avakov, who did not want Petro Poroshenko to win the elections. The authors of the dossier argue that the Korotkikhs could have had a broader motive: facilitating the political rise of the so-called “Dnepropetrovsk clan” led by the wanted Ukrainian oligarch Igor Kolomoisky, who aims to align Ukrainian politics with Russian interests.

After Vladimir Zelensky’s electoral victory, Sergei Korotkikh actively joined the anti- Western voices in the pro-Russian media, including on the TV networks of Putin’s godfather Viktor Medvedchuk. In particular, he helped spread Russian propaganda about “external control of the country,” George Soros, and Ukraine’s loss of independence upon joining NATO.

A recipe for success

Sergei Korotkikh explained his dubious luck in Belarus and Russia as follows: “I left right on time when I needed to, when I was on the run. I paid money — a lot of money — to avoid going to jail.” His friends, including Valery Ignatovich and Maksim Martsinkevich, as well as pupils in the RNU and the NSO, ended up behind bars. The Russian authorities put Martsinkevich’s followers and those who fought on the side of Ukraine in Donbass on the international wanted list. However Sergei Korotkikh himself hasn’t been pursued either in Belarus or in Russia.

The authors summarize their dossier by calling Sergei Korotkikh an agent of Russian influence: “From 1993 to 2020 […] there have been no known cases of criminal prosecution [of Korotkikh] as a suspect either in the Russian Federation, in Belarus, or in Ukraine, nor have there been any administrative arrests. The Russian Federation has not put him on the international wanted list for his participation in illegal right-wing extremist organizations or his other active right-wing radical activities, nor for his participation in hostilities in the ATO zone as part of the Azov battalion. [All of this] is a sign of the Russian Federation’s patronage of the Korotkikh, a sign that he is an agent of Russian influence.”

Translated by Sam Breazeale and Cornelia Krüger from Respond Crisis Translation