Before the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Mariupol, the largest city on the Sea of Azov, was home to some 500,000 people, and local industrial enterprises operated for the benefit of the whole country. On February 24, Russian troops encircled the main city of the Azov region from the southwest, east and north and began to destroy it. More than ten thousand civilians are known to have died and hundreds of thousands forcibly removed to Russian territory. Zaborona spoke to a family who spent 55 days in the besieged Mariupol before the occupiers took them to Russia, and from there they managed to escape to Europe.

On the morning of 24 February, 61-year-old Anatoliy Kinashchuk did not go to work in his usual role for the first time. He had been living in Mariupol for several years and worked as a sound engineer at the Molodizhnyi Palace of Culture. It was the most fashionable area of the industrial seaside city. There was Teatralna Square, which had recently been refurbished so that it was indistinguishable from squares in Western European cities; not far away there was the TU platform, where the new Ukrainian culture was developing, and the Greek Cultural Centre. In the Molodizhnyi, performances were staged and conferences held – in the near future, it was to be transformed into the Centre for Contemporary Art.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

“Early in the morning my wife says, ‘That’s it, Tolik, there’s trouble,'” Tolik tells me. This is not the first time he has been in trouble. In early 2015, he took one of the last evacuation buses out of Avdiivka, an industrial town near Donetsk, where he had lived more than half his life. At the time, Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) troops, a large part of whom were Russians, tried to take over the town and shelled it mercilessly. After this shelling, local schools even introduced self-defense lessons for children, in case something like this happens again.

For everyone, the Russian invasion of February 24 started the same way, and for each one it was different.

“When Putin made the statement that there was no such country [as Ukraine], that it was all man-made, that’s when I got convinced: well, if he says such things to the whole world, then something will happen,” Tolik says.

For the first couple of days, Mariupol lived normally, not bombed yet. You could hear echoes of gunfire from the east, from Shyrokyne. The sounds, Tolik says, were transmitted by the sea.

The real problems began when the railway bridge in the town of Volnovakha, through which a train from Mariupol passed to the northwest, was blown up on February 28. Mariupol residents then realized that they were cut off from the outside world and it would be difficult to leave. At that time, Volnovakha was occupied by the Russian military along with proxy DNR troops. On the same day Lena, 29, Tolik’s wife, moved with the children from their flat to the basement of the house where her parents had an apartment. The building was near Molodizhnyi Palace of Culture, where Tolik worked, and was protected from all sides by other houses.

For the first few days it was just Lena and her children and two old ladies hiding in the basement. But by early March, as the pressure on Mariupol intensified, neighbors began to gather in the basement.

“And then the real strikes started,” says Tolik.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

Theatrical bomb shelters

The houses in Mariupol were not prepared for the Russian invasion. The fact that the Russian proxy DNR forces tried to seize the biggest city of Azov in the spring of 2014 was no reason to set up shelters in residential buildings and build proper bomb shelters. No one expected that Russia might launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine and use a full arsenal of weapons, from cluster bombs banned by the Geneva Convention to airstrikes and chemical weapons.

Since 2014, despite the war in Donbas, Mariupol has been actively developing: fashionable clubs have appeared in the city, an intellectual environment has emerged and there was a plan to establish a new university. Mariupol became a new center of attraction in the region, and thousands of new citizens moved there despite the disastrous environmental situation, which was worsening due to the key metallurgical enterprises – Azovstal and Illich Iron & Steel Works.

When in winter 2022 the city started to be shelled from all sides, locals went to hide first in real, equipped bomb shelters. One of the largest was in the Drama Theater in the city center, a five-minute walk from where Tolik and his family lived. About 1,500 people were hiding in the premises of the theater. On the pavements on both sides of the building they wrote in large letters – so that it could be distinguished from the air – “CHILDREN”. On 16 March, the Russians dropped a bomb on the theatre – it destroyed almost the entire building. Representatives of the Mariupol city council later said that three hundred people inside survived. No one said how many died. Tolik believes that more than five hundred people may have died under the rubble (the same figures are confirmed by an Associated Press investigation). He says that people hid not only in the bomb shelter, but also in the rooms on different floors of the theatre.

Around the same time the Russians shelled the Molodizhnyi Palace of Culture. There was a bomb shelter there too, and about three hundred people were hiding in it. The Molodizhnyi building was built more than a hundred years ago, the Continental Hotel was located there back in the days of the Russian Empire, and its shelter was, as Tolik says, “mighty”. He adds that people from all over the city came to the shelter, thinking it would be a safe place. They stayed there day and night.

-

Molodizhnyi is on fire. Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

After another strike, Molodizhnyi caught fire: a rocket flew through the roof of the building to the floor where the local TV-7 channel’s office was located. It happened in the middle of the night. Tolik remembers well how he ran to save people. Smoke and carbon monoxide from the fire went down through the pipes to the basement. Things caught fire. One hundred and fifty people – families with children, the elderly – tried to get out of their shelter in the darkness. They abandoned their bags, documents, food supplies, ran across the streets under gunfire, fled in a panic in all directions. In the end, says Tolik, everyone got out alive.

-

Molodizhnyi after the shelling. Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk -

Molodizhnyi after the shelling. Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

-

-

Molodizhnyi after the shelling. Photos provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk -

Home basement

Some of the people hiding in the Molodizhnyi moved to the basement where Tolik was sitting. The basement was quite spacious, 64 square meters – the size of a standard three-room flat, only without the partitions. There was a small hall in front of the cellar entrance. The tenants put a bucket there and used it instead of a toilet. And next to the bucket, on the shelves, they placed food.

“We did that in case a bomb fell on us and blocked the passage, so that some food could be left around,” Tolik explains.

Twenty-two adults and seven children were living in the basement: the oldest kid was seventeen years old and the youngest was five months old. Most of the roomers were seeing Tolik for the first time.

“The company was diverse, including a drama theater performer, an employee of the city water supply company, and an engineer from the Illich Iron & Steel Works,” Tolik says.

“People were very different, but we bonded”.

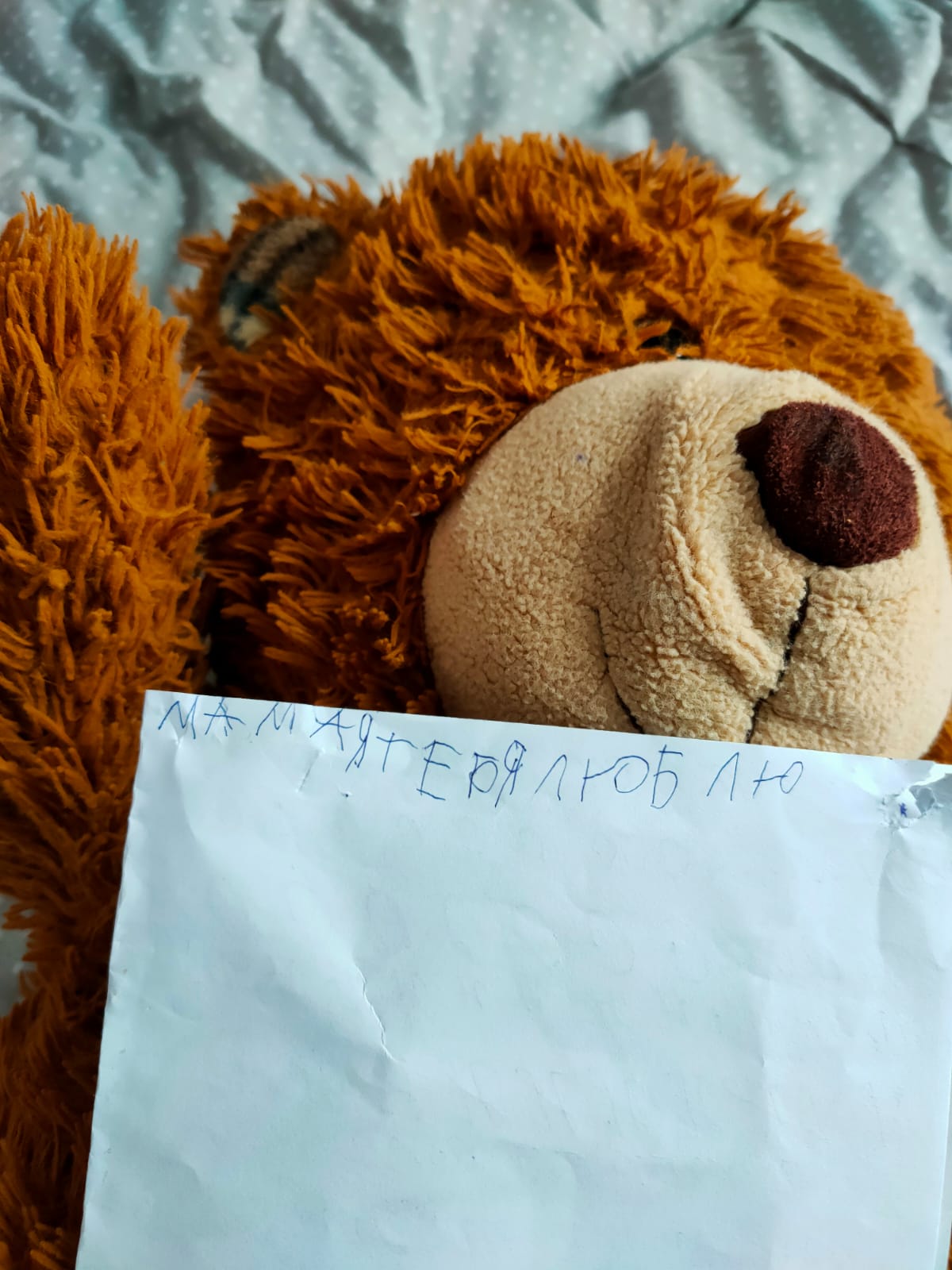

“We both ate in the basement and went to the toilet there, and had fun. My wife gathered the children, they lit a candle and read – she taught them, so that the children would not become dull during this time,” says Tolik.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk -

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

The days in the basement went like this.

Tolik says, they woke up at the first explosions – the shooting started at four or half past four in the morning. As soon as it dawned, the men – that is, Tolik and his new comrades – got up, brewed coffee and discussed the plan for the day: to go to get water or not, whether or not there would be bombing in their area. They took water from a spring a couple of kilometers away from Azovstal, near Malofontanna Street. And when drawing water, they saw shells bursting over the plant. These trips to get water always carried risks.

Infographics: Snizhana Khromets / Zaborona

“We tried to get energized in the morning and plan our day so that it would be as productive as possible for all of us,” says Tolik. “If we heard that there was bombardment closer to Azovstal, where we were getting water, we didn’t go and waited until it calmed down and started on the other side. We always went quickly to get water, because we had empty tanks, but on the way back we walked slowly, full, and we became a potential target [for attack]”.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

Gradually the place became unsafe: mortars started firing there. And once Tolik found out that a man who was drawing water from the spring there had been killed – and his “brigade” has not gone there since. They began to draw water from the well of the broken Greek Cultural Center.

Getting food

Food was also hard to come by. As early as the beginning of March, looting started in Mariupol: most grocery shops and supermarkets had been broken into and looted. Some things people could buy in the Port City shopping center, and they often stood in queues for hours, risking being hit by gunfire. The shops in the center had long been empty, and food was brought to the basement by the occasional volunteer. At some point it became clear that food would have to be obtained by any means necessary.

Tolik shyly admits that the food was taken from shops and warehouses that had already been broken before them. Once they found a looted cheese dairy with unripe heads of cheese, which they also did not shy away from. They found food in the flats of neighbors who fled and left canned goods, cereals and sugar. They dragged everything to the basement. The roomers cooked on the fire in the courtyard. They tried to cook so that the smoke didn’t go high, otherwise mortar shelling could start.

-

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk -

“When we returned to our cellar with our loot, everyone pounced on those bags, it was so touching,” Tolik recalls. – And when we managed to find toys for the children, they rejoiced like it was a holiday and immediately forgot about the war.”

During the day the city was bombed by artillery, Grads and fighter jets, and as soon as dusk fell, the streets were drowned in darkness and silence. At night the artillery was silenced, and only occasionally, “apparently for prevention”, Tolik adds, the mortars fired.

All of this was actively discussed in the basement. Tolik said that there were several “vatniks” (supporters of Russia) among the neighbors – they tried to blame the Ukrainian army for the shelling of Mariupol.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

“There’s a plane flying, dropping bombs on the Palace of Culture, on a shop near my house, for example, and they say: they are bombing Azovstal,” Tolik recalls. “And I said to them: the pilot can see exactly where he is dropping the bombs! It came to a vociferous dispute: I was proving to people that the Russian pilots knew that they were bombing civilian houses. When the conversation came to a standstill, I gave them one last argument: Was it Ukraine that attacked Russia? Did you call for the “Russian world” to come? It came and liberated you – from your flats, from your belongings, from your former normal life. After that they shut up and didn’t talk to me for a while.”

It happened that some neighbors secretly ate food from the common stock while others slept. After a few such incidents, Tolik says, they had a serious talk, and it did not happen again.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

Despite the controversy, the basement residents lived peacefully and coped with the challenges of the times. One night, a shell hit a neighboring building, and the entire male basement staff ran to extinguish the fire. None of the men had any fire-fighting experience, so they acted on their wits: they carried technical water from the basement to the roof, found fire extinguishers in the Palace of Culture. The next night a shell hit another building nearby and smoke began to descend into the basement. Tolik was afraid that the basement might catch fire, as it had already happened with the bomb shelter at the Palace of Culture. He decided to evacuate the tenants.

“It was the worst night for our women and children,” he says. “Everyone was running sleepily outside under shelling, crying, freaking out, while we carried our belongings and children to the basement of the Palace of Culture. The night was bright, stars shone in the sky, but it was also very scary. The three of us went to save our building and all night long we were vigilant, standing under fire, climbing onto the roof and putting it out with fire extinguishers. We felt like heroes, some adrenaline kicked in. Eventually the smoke cleared. In the morning we came for our women and children, and everyone was crying with joy that we hadn’t abandoned them and that we were going back to our home basement. Sounds scary, doesn’t it? But the basement really did become our home.”

-

Anatoliy Kinashchuk

Nightmares of the occupation

Determining where the front line lay in Mariupol was difficult for the citizens. By early April, most of the city was under control of the Russian troops. At the same time, the whole world learned about Russian atrocities in Bucha and Irpin near Kyiv, near Chernihiv and Sumy after the Russian army withdrew from its positions in the north and regrouped to the east.

The basement on Myru Avenue had no communication. Neither Tolik nor the other residents knew what had happened hundreds of kilometres from their home. They had heard nothing of the killing of civilians, of torture or rape. Their relatives outside Mariupol tried hard to contact them to find out if something terrible had happened to them.

Meanwhile, dead bodies came into sight on the streets of Mariupol. Tolik saw several corpses with his own eyes on Myru Avenue, in the heart of the city. He had heard even earlier that the local morgues were already overflowing with bodies, and that the utility services could not go out and bury people in cemeteries because of shelling – it was dangerous. He also heard that the municipal workers recommended to put the bodies in the coldest place in the flat or, if there was no such possibility, to move them outside, in the shade. Tolik photographed one such corpse lying in the shade on Myru Avenue.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

One day a shell hit the house of his basement neighbour, Denys. Before living in the basement, he resided in a flat with a five-month-old baby, his wife and her elderly father. A shell killed the father as he slept in his room. He was buried in the garden of a private house near the Palace of Culture. Over two long months, says Tolik, a small cemetery was set up in the garden: the dead were carried there from all over the neighborhood.

At some point, DNR troops entered the area where Tolik lived. In the evening he was sitting in the basement and heard someone talking and walking loudly nearby. Together with his cellar mates, they went up to the flat on the floor above, and someone commanded: “Everyone go downstairs quickly”. They left. In the morning, they went up again and were met by DNR people in the flat.

“They made themselves comfortable, hostile,” says Tolik. “They ate our food, drank our water. They said that they would live here for some time and that they would have a stronghold here. We understood that now, while they were here, Ukrainian shells could come at us if ours [Ukrainian troops] started to attack. But we couldn’t ask them to leave…”.

A few days later, the DNR military left the flat as suddenly as they had occupied it, leaving a legacy of two boxes of grenades, a bulletproof vest and a jacket. They said they would come back and get it, but they didn’t. They were followed by another group of DNR people, but they also quickly left. That time the enemy started to bomb Azovstal, where a regiment of the Azov, National Guard subdivision, had fortified during the fighting.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk -

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

Talking to terrorists

Tolik tried to use every opportunity to talk to the DNR fighters. Unlike the Russians, who preferred not to go into the epicenter of hostilities, he had something in common with these people, primarily it was Donetsk, where he had lived and worked for many years. Most of the DNR military, he said, were brought to Mariupol precisely from Donetsk.

One day at a checkpoint not far from his home Tolik got into a conversation with one of them.

“He suddenly said to me: ‘I’m so f*cking sick of this Russia,'” Tolik recalled. “I looked at him cautiously: is he a provocateur? And he goes on: ‘I, he says, am a worker of a water supply company from Donetsk, they took me away on February 23, saying that in 72 hours we’ll bring you back, we’ll take Kyiv – and then we’ll let you all go. Now we are meat, he said. Then I talked to another guy, a programmer from Donetsk. He says: Russia threw me here, but I don’t need it. And, he says, I’m afraid that if we start “liberating” Avdiivka, Mariinka and Pisky, Ukraine will do to Donetsk what we did to Mariupol. And that’s our home there.”

Without food and water

Sometimes Tolik, together with his new basement friend Borys, went for a walk around the neighboring houses to find out what was happening, if anyone needed help.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

It was the middle of April. The center of Mariupol was already controlled by the Russian proxy troops of the DNR, and the outskirts were controlled by the Russian army. Most of the houses were destroyed. Tolik rarely met passers-by on his way. More often he saw dead bodies on the street.

Suddenly, Tolik heard an elderly woman shouting from the window of a dilapidated riser-block: “I’m thirsty, I’m thirsty! People, I’m here, give me the water…”

He shouted back, “Where are you? On what floor? The woman fell silent and then started screaming again. Tolik could not understand what to do. He returned to the basement, got a bottle of water and started looking for the old woman. Judging by the voice, he mused, this was the second or third floor. He found the entrance, but it was padlocked. Together with Borys, they tried to break the door – it did not work. It was not possible to climb through the windows on the first floor – there were bars.

Suddenly, a door opened in another entrance, and an old lady came out of it. Tolik asked her if she knew who lives in that riser-block and how to get into it, because he brought water. The old woman replied: “Give me some water, I’m thirsty too.”

“We gave her this water and left with the thought that we were leaving a person to die,” Tolik recalls. “We couldn’t help that woman, and I can’t forgive myself.”

Then, Tolik recalls, he brought that granny from the other entrance porridge and a loaf of bread.

“I opened the door, gave her everything, and she looked at me in silence and just pounced on the food right there,” he says. “I closed the door and left.”

Animal roommates

The basement was a cat house: along with 29 residents, there were six cats. They were fed with whatever food was left over from the communal supply.

Often other dogs, both purebreds and mongrels, came into the cellar. They wanted warmth and food. Tolik says that they had to chase them away: there was not enough food for all of them, so they gave them a little and sent them away. One day a young purebred Husky dog ran into the basement.

“I said to her: goodbye, go away!”, says Tolik. “I grabbed a twig, threatened her. She looks at me and does not want to leave. I start talking rudely to her, and she stands still. I slam her with the twig lightly, and she turns her back on me and starts walking away in small steps. And then she turns to me and whines angrily. As if she wanted to say to me: “Why are you chasing me away, human, I am a nice dog…”.

No matter how sorry the cellar tenants were for the animals, they could not keep them.

Desperate wait for evacuation

The shelling in Mariupol did not stop for an hour. Every day Russian tanks and fighter aircrafts hit a house or a hospital. There was no communication, no electricity and no fuel for the second month. Those citizens lucky enough to have cars and petrol were able to get out before anyone else. The rest were forced to look for an organized exit.

The hopes of the locals for evacuation dwindled with each passing day. Some managed to catch a bus to occupied Berdyansk, from where they could get to Zaporizhzhia and Dnipro, but increasingly, the Russians were taking Mariupol residents to occupied areas in Kherson region, Donbas and Crimea – and getting out from there to Ukrainian-controlled territory was much more difficult.

At one point, it became known that the Russians were packing the townspeople into buses and sending them to Taganrog in the Rostov region, and from there taking the Ukrainian families to remote parts of Russia.

No one in Tolik’s basement had a car. Periodically he went out in search of drivers who could take his family with them.

“Once a corridor was organized for people to leave in their cars,” says Tolik. “Thirty cars came out. A woman was walking towards us with a boy about seven years old and a baby in a stroller. She was crying, waving to these cars, and none of them stopped. She was in despair – everyone was passing by. People were only taking out their own relatives. That’s when I realized we wouldn’t get out”.

It was the 55th day of the invasion. This day, 19 April, is referred to as the start date of a new phase of fighting for Donbas, where Russia has redirected most of its forces. On that day, the head of the Ministry of the Occupied Territories, Iryna Vereshchuk, announced that the humanitarian corridor for evacuation from Mariupol would not be able to open again. Tolik heard a car drive up to the Palace of Culture. He ran out, as usual, to see who had arrived – he was used to the fact that if a car arrived, it meant either bread or a small ration. The Russians usually brought such “humanitarian aid” together with propaganda newspapers and filmed the food distribution.

This time he saw the same thing. A large black jeep with Russian number plates was parked outside the courtyard and two men were handing out food and a “Novorossiya” newspaper. Tolik took a few loaves of bread for himself, but suddenly a thought flashed through his head.

“I said, Lena, go and ask if they can take us away or not,” Tolik recalls. “I went to the basement, ten seconds passed and I saw Lena running and shouting: run, get ready, they’re taking us away! Our bags were already prepared in the basement.”

The Russians put Tolik, Lena, the three children, their grandmother and their bags in the trunk, right on the newspapers, shut the doors and drove off. The jeep took them to the village of Mykilske, north of Mariupol, and from there they were taken to Novoazovsk on the border with Russia and transferred to the so-called “filtration camp”. All those who entered this area were questioned by Russian FSB officers. They searched their phones, checked their correspondence and social media posts, asked questions about ideology, stripped them naked, and looked for tattoos.

Tolik knew this was going to happen. He deleted his social media pages in advance, as they showed he was a patriot of Ukraine, and hid his photos. He also prepared answers to ideological questions.

“I was asked what my attitude was towards the Russian army, Russia and the war,” he says. “I answered neutrally: nobody needs this war, it is deaths on both sides. After that we were released.”

The bus took Tolik and his family to Taganrog in Rostov oblast. The passengers – about fifty people – were dropped off at the railway station and lined up in front of a man in civil clothes. He made what seemed to be a prearranged speech, saying that everyone who came here from Mariupol would get a free train ride, and that where that train was going there would be free accommodation, food and work for them.

“Someone asked him, where is this train going?” says Tolik. “He replied: To Perm. We quickly grabbed our things and ran [away], to take the train to Rostov.”

A couple of days later, Tolik and his family got to St. Petersburg, and from there by car they drove to Estonia. Tolik called me as soon as he crossed the border. He said: “That’s it, we’re free!”

I asked Tolik what happened to those people from the basement with whom he lived for almost two months. Were they all able to move out? Tolik answers with sorrow in his voice: “There are only we who have left. The others are still under bombardment. We just wanted to leave more than others, we were dying there already. ”

Tolik sent me a photograph, taken five minutes before departure. It looks like a family photo: the basement tenants pose for the camera with a guitar and balloons and smile as if there is no war.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk

I asked Tolik what he and his neighbors have learned in their 55 days of living in besieged Mariupol.

“We learned how to be friends,” he answers. “We learned to appreciate people, to appreciate life, food, water and human kindness. And I have come to love my country more. Whatever it is, whatever the president or the government is – we are all human beings, and the most important thing is that our president changes, he is not the tsar.”

In the following, Tolik sends me a recent photo from Estonia. He’s posing with Lena and the kids by the lake. They smile cautiously. They’re really safe now. They got out.

-

Photo provided by Anatoliy Kinashchuk