Kyiv will have its fifth Equality March this year, and September will be Pride Month, which will include special lectures, films, and exhibits. And while events like these have regularly been the targets of homophobic attacks in the past, Kyiv has about a dozen LGBT organizations that are prepared to provide psychological and legal support to members of the LGBT community. The same can’t be said for Ukraine’s smaller towns, however, where establishing even a single LGBT center can be a challenge. Zaborona journalist Anna Belovolchenko traveled to Mykolaiv, where she spoke with various LGBT activists from rural Ukraine about their work, their goals, and the problems they face.

A bomb threat in Mykolaiv

At a mall in Mykolaiv, two minutes’ walk from the city’s LGBT association, LiGA, people are being evacuated. An entire block in the city center is blocked off. An ambulance, the police, firefighters, and employees from Mykolaivgaz, the local gas company, are rushing to the scene.

“We’re done hunting down reprobates one by one. Today we’re burning down the center of the depravity, just as the Lord struck down Sodom and Gomorrah,” read a letter that was anonymously sent to local media and association heads the previous day. “Our incendiary explosive device will go off during the day, when there will be the most witnesses.” The reason they gave was that “people must see the inescapable fate of the scum who are denigrating our country.” A picture of an explosive device was attached.

For locals, this threat was nothing new. The first time LiGA received a letter like this was December 28, 2020. They initially chalked it up to a New Year’s prank, but the police and first responders came nonetheless. It turned out that they’d received letters of their own; Ultimately, no explosives were found, a letter allegedly written on behalf of “the white population of Germany” claimed that someone was planning to “kill everyone with a bomb.”

The second episode occurred on January 18. This time, unidentified people announced they would “burn down the homes” and “slash the families and loved ones” of LiGA employees. They referred to members of the LGBT community as pigs, while simultaneously capitalizing the word “You” as if to convey respect.

Photo: Mykola Donduk / Zaborona

The last time this happened, when they closed off the entire block, was on April 8 of this year. While the police did reluctantly open a criminal case, LiGA was not acknowledged as the victim. Now, law enforcement officials are collecting the personal data of everyone involved in the organization’s work, and bringing them in for questioning without lawyers present.

“Do they think we’ve been sending threats to ourselves?” asks LiGA head Oleg Alekhin. It’s unclear to him why law enforcement would need all the personal information of the people being targeted, especially given that there are about four thousand people involved in the organization, including employees, volunteers, and clients from Mykolaiv, Odesa, and Kherson.

Alyokhin is confident that all of this is being done with one purpose: to end the organization’s work and intimidate them.

LiGa head Oleg Alyokhin. Photo: Mykola Donduk / Zaborona

“They want us to go back to the 90s, to gather together who knows where, in private clubs, and to stop talking about LGBT issues, to stop talking about how we have families and we want to live in a free country. The government doesn’t protect us. Even Zelensky said when he came last year that Mykolaiv is still considered a ‘bandit city,’” Alyokhin said.

Bohemians and bandits

In the 1990s, one popular street activity in Mykolaiv was doing “repairs.” This meant, in the local jargon, beating up anyone who stood out. According to Alyokhin, standing out could mean something as small as wearing a beret or a long, bright raincoat. And if there wasn’t any sex in the Soviet Union, there certainly couldn’t have been any gay or lesbian people. People believed they’d been imported from the West, said Alyokhin.

In Soviet times, Mykolaiv was a closed city. Part of the Soviet military-industrial complex, the city was difficult even for Soviet citizens to access, not to mention foreigners.

“It was a city of factory workers, isolated from everyone else. And when they opened it, after the Soviet Union’s collapse, it lost its potential — people started leaving,” said Alyokhin. “Quasi-legal businesses that were closely intertwined with the government appeared [in place of the factories].” And that’s how Mykolaiv gained notoriety as a “bandit city,” according to Alyokhin: the criminal underworld had a strong influence on how city residents treated one another.

But there’s another side to Mykolaiv’s history. In Soviet times, it was a hub for so-called Bohemians: artists and members of the intelligentsia.

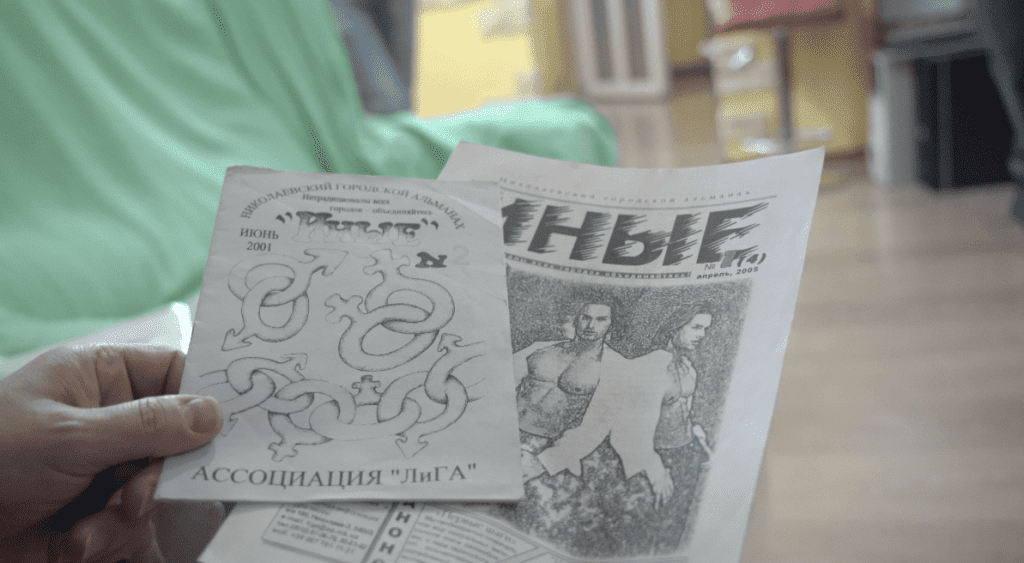

There were parties where guests could just be themselves, and discussions of how to change the city’s view of LGBT people. A group of frequent guests at kvartirniki, or underground concerts and readings in people’s apartments, even reached out to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), which helped them access magazines, brochures, and other sources of information about life in the West.

But it wasn’t until 1995 that the group decided to come out publicly, after one of its members won a Dutch writing contest for lesbians.

“That was our first step out of the closet,” said Alyokhin. “Part of our community decided it was time to move forward and be visible. That’s when we decided to start the organization.”

Photo: Mykola Donduk / Zaborona

It took a year to get the necessary documents approved by officials. According to Alyokhin, the authorities didn’t understand “what gays and lesbians are,” and advised them to write “non-traditional orientation” instead. But the activists insisted, refusing to use any veiled language — the documents would clearly say “LiGA: the Mykolaiv Organization of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual People.” They finally got approval in December of 1996, and LiGA became the first official LGBT organization registered in Ukraine.

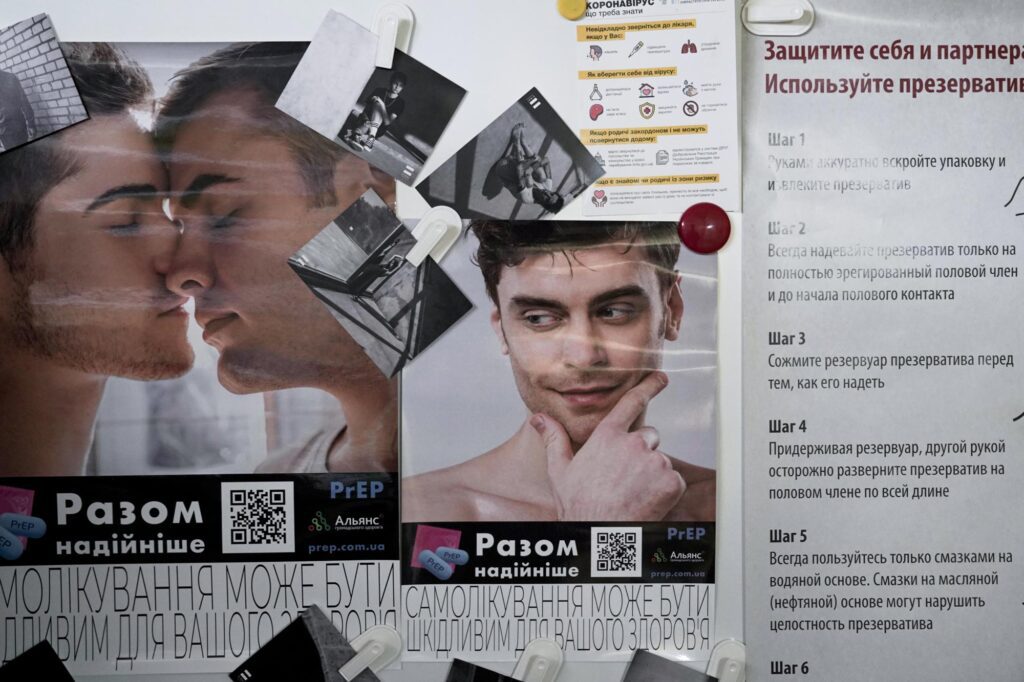

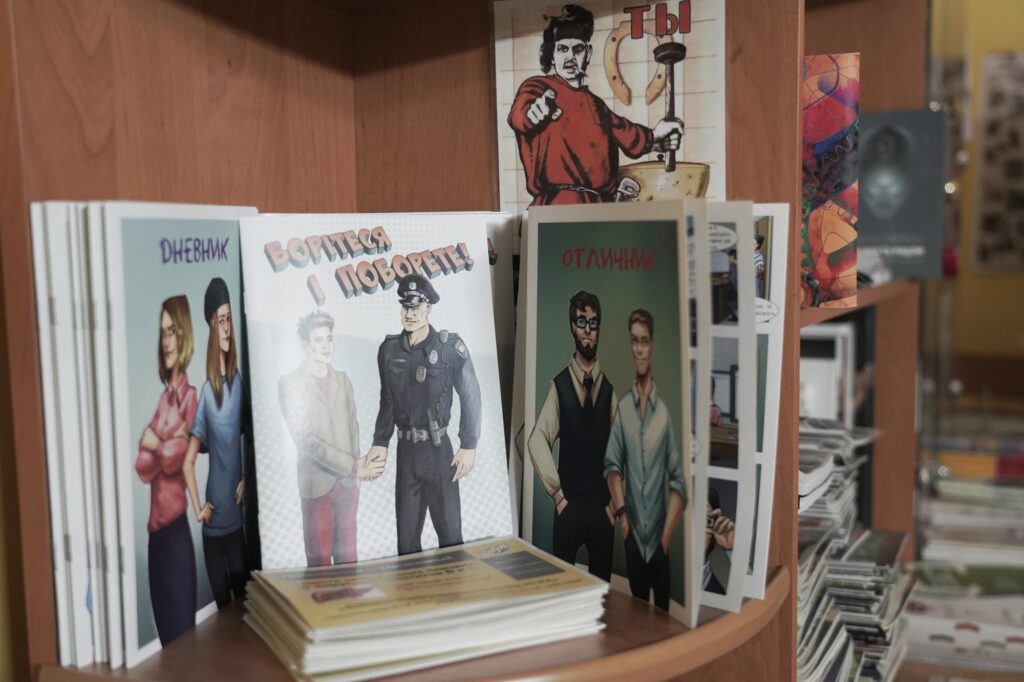

For the first few years of its existence, the LiGA team focused on creating a club for same-sex dating. They even held dates at a cafe in the courtyard of the regional council, where one of the members worked. But over time, their emphasis shifted to information campaigns, seminars on same-sex relationships, and HIV/AIDS prevention.

The LiGA office in Mykolaiv. Photo: Mykola Donduk / Zaborona

The more conspicuous you are, the more dangerous it is

Since 1996, LiGA has gradually acquired its own facilities, including branches in Odesa and Kherson; launched programs for engaging with the authorities and with society at large; and begun providing psychological and medical support to members of the LGBT community.

“Every year, the more we spoke about ourselves publicly and the more people discovered us, the more people started paying attention to us,” said Oleg Olyokhin. This included attention from far-right groups, religious organizations, and the local authorities.

LiGA head Oleg Alyokhin. Photo: Mykola Donduk / Zaborona

In 2008, Mykolaiv’s city council banned a flash mob recognizing the International Day Against Homophobia. The official reason behind the decision was that the event would create a threat to the public order and disturb the peace and equilibrium, which would lead to mass clashes and conflicts.” It was later discovered that representatives of religious groups had demanded the city ban the flash mob the previous day.

In 2009, LiGA organized an event called Rainbow Spring, a series of photo exhibits, lectures, and flash mobs like the ones held today at Kyiv Pride. The local government initially demanded the organization cancel all of it, but LiGA refused, so the city sued them. Hearings, interrogations at the prosecutor’s office, and accusations of threatening national security ensued.

“At the interrogations, they asked me why I hadn’t left yet,” said Alyokhin. “I said fine, let’s say I leave — and what about everyone else? Or should I make an announcement, gather all the gays and lesbians, and wander around Ukraine for the next 40 years?”

The confrontation with the local government lasted for a year — and since then, Rainbow Spring has been held in Mykolaiv every year. According to Alyokhin, the Mykolaiv city council doesn’t help, but also stopped getting in the way. Official government bans, however, have been replaced by more sinister threats.

Today, LiGA’s office is surrounded by a fence and a gate almost two meters tall. Surveillance cameras record everything that happens outside and everyone who tries to enter. And all of this was built for a reason.

In 2009, a photo exhibit in the Mykolaiv House of Artists dedicated to LGBT rights was interrupted by 30 “boys in athletic pants,” as LiGA put it. A few years later, unidentified people damaged the facade and windows at the organization’s office. As a result, a fence and cameras were put up around the LiGA building, but they were soon broken as well.

In 2018, the far-right organizations Right Sektor and Sokol tried to break into LiGA’s office. They demanded the Ukrainian flag be removed, according to Alyokin, arguing that gay people can’t be patriots. Last year, members of the radical group Tradition and Order “took an interest” in LiGA. Since then, they’ve regularly covered the fence with offensive flyers.

“Community centers like ours shouldn’t have to be surrounded by tall fences, and shouldn’t have cameras around them. All that’s left is to get guard dogs and guard towers with automatic weapons (for security reasons),” said Alyokhin. “But then we’d kind of become an LGBT-only zone. And I don’t want to live like that. I want us to be open.”

LiGA head Oleg Alyokhin. Photo: Mykola Donduk / Zaborona

According to Alyokhin, when one group of people tries to hide something from another, the result is fear. It creates confusion, since people don’t know what to expect. But if things are open to everyone, dialogue becomes possible. That’s the reason why LiGA has never hidden the address of the community center and never withheld the organization’s activities from people living nearby.

Better safe than sorry

The Lutsk branch of the all-Ukrainian organization Insight has been around for two years. Unlike LiGA, however, Insight keeps its office address carefully hidden. Only people who have pre-registered can go to the organization’s events, and the Facebook group is kept closed. In order to join, you have to apply — though they do accept anyone, whether you’re a member of the LGBT community or just a friendly person.

According to Yana Lis, the coordinator of Insight’s Lutsk branch, when she wrote on social media that she was going to take part in the Equality March, she started getting threats of a massacre in her private messages. The organization had never faced anything like it. Usually when events need protection, the Lutsk police come. Law enforcement officers even attended a public lecture about human rights organized by Insight. According to Lis, however, it’s better to be safe than sorry.

“On one hand, I’d say Lutsk is pretty tolerant,” she said. “For example, on an everyday level, the situation is getting much better among young people. They’re more accepting of LGBT people. And we held our march on March 8 without any problems — there was no pushback. But on the other hand, the city council is still homophobic. They regularly make decisions to ban the LGBT community’s public protests, and they’re anti-feminist.”

Yana Lis

At this point, Insight isn’t focused on establishing a dialogue with the authorities. Instead, they’re concentrating on developing the LGBT community, but they are optimistic about starting a dialogue with some feminist deputies in the future.

According to Lis, being part of a nationwide organization has really helped Insight’s Lutsk branch develop.

“They’ve helped us out with lectures, offices, building the community center. It would be really difficult without them,” she said.

The Lutsk branch has about one hundred members, which is a lot, according to Lis, especially for one of the oblast’s smaller centers. She also pointed out that a hundred people is far from all of the LGBT people in the area. A lot of people still can’t come out because of homophobia at work, for example, or in their families.

“Sometimes people come to us from small towns in the oblast. They come from Rivne, a neighboring town, because there aren’t any organizations like us there,” she explained. “It’s important for people to spend time around like-minded people, learn things, or just realize that they’re not alone, they’re part of a community.”

Women protesting against discrimination in Lutsk, 2020. Photo provided by Yana Lis

“Turn down the temperature to keep things from burning”

In Mariupol, an organization called Istok has made it its mission to build a strong LGBT community through its community center, Equality EAST. According to the Istok team, the center is one of the few safe places for LGBT people and allies in Eastern Ukraine.

“The only thing we don’t allow is hate,” said Equality EAST coordinator Kirill Maistrenko. “Anyone can come and meet us, watch lectures, and use our HIV/AIDS prevention services.”

Kirill Maistrenko

The community center opened two years ago, and while they dream of organizing a march in Mariupol like the one in Kyiv, they’re currently limited by circumstances beyond their control.

“Weapons are relatively easy to access in this region, and there are a lot of military servicemen. In other words, it wouldn’t be safe,” said Maistrenko. “We need to remember that every action has a reaction. And we have to think about safety first.”

It’s unclear what would happen if this factor were removed. On one hand, after the center was opened, city residents filed a petition on the city website demanding its closure and calling it a place of debauchery. On the other hand, the authorities refused, arguing that there were no grounds for closing the center.

“It was a precedent for us, and an indicator of how well the government can work,” said Maistrenko. “I think it’s connected with the city’s image — it’s difficult to call Mariupol a place of debauchery. And we’re trying to implement socially meaningful initiatives in the city, trying to be helpful, so why would they shut us down?”

The team has come to the conclusion that there’s no “extreme homophobia” in the city, and they’re confident it’s not the case that “walking down the street is dangerous, but it’s likely you’ll run into something unpleasant.” The police don’t register complaints about hate crimes, and doctors in the local hospitals speak negatively about LGBT people.

The community center address is openly accessible and its employees don’t hide their social media profiles, even talking openly about their work. The far-right organization Tradition and Order apparently has a group of members in the area, but Equality EAST hasn’t received any attacks or threats from them. According to Maistrenko, this might actually be a result of the group’s openness.

“The main thing is that weren’t not only consolidating the LGBT community in one place — we’re also building a friendly community. We’re helping people understand that this is normal, that there are no gay battalions, like Skabeyeva said [Russian propagandist Olga Skabeyeva claimed on May 17 that Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky was sending ‘columns of Ukrainian homosexuals’ to Donbas. – ed.] We collaborate with other organizations and give them a facility if they need. And our membership is growing, we’re hearing from people from Central and Western Ukraine. People come from Dnipro, Zaporizhia, and Kryvyi Rih,” said center coordinator Inna Shumurtova.

Inna Shumurtova

As the Equality EAST team willingly admits, they have an ambitious goal: to beat homophobia. It won’t happen overnight, but if they can “turn down the temperature and keep things from burning so much,” that alone will be a victory.

No certainty

Ukraine has the lowest rate of LGBT acceptance out of 16 European countries, including Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic. When asked whether society should accept homosexuals, only 14% of Ukrainians responded in the affirmative, according to a survey from the Pew Research Center. A survey among Russians found the same result. The survey was conducted in 2019. In addition, the rate has been falling every year: in 2002, 17% of Ukrainians were willing to accept homosexuals, and in 2011, it was 15%.

“On one hand, things have gotten better because tolerance is increasing. This is a general tendency in the West,” Oksana Pokalchuk, director of Amnesty International Ukraine, told Zaborona. “But on the other hand, the use of diversity to manipulate people for political interests has also grown. People’s fear of ‘the other,’ whether that’s the LGBT community, migrants, or other provocative groups, is used to unite more people through hate.”

Oksana Pokalchuk

In the past, people might not know what it meant to be gay or lesbian, so they didn’t have any opinions about it. But now they say, ‘I’ve never meet a gay person, but I know what they’re like.’

“Corrupt politicians use the rhetoric of protection. ‘We’ll protect our village/city/district/region from…’ and they insert whatever they want. Because of the human psyche, people reduce everything to “me,” “us,” and “they.” In order to learn anything new, you have to apply effort. But there’s a strong stream of information telling you that it’s not you who’s guilty — it’s this ‘them.’ And people start uniting against whoever it is to protect their land, their children, even their cats,” said Pokalchuk.

Religion has a strong effect on how people view LGBT people. Usually, according to Pokalchuk, cities are less religious than rural towns, which means people there are more tolerant of LGBT people. But the prevalent religion in an area, and the interests of its representatives, also play a role.

The situation for LGBT people can also depend on what other resources and problems the region has. The greater the need to distract people from real problems with imaginary enemies, the harder life gets for LGBT people.

“Whether a city is close to the front or not, based on my observations, doesn’t have an effect on people’s attitude toward LGBT people, or on LGBT initiatives,” said Pokalchuk. “The question is how easy it is for people to gather peacefully, for example. And also whether they’ve matured to the point that they can gather together and support one another. After all, to become an activist, you have to travel a difficult path.”

There are places where people are taught from childhood to keep a low profile, and places where things are easier. But according to Pokalchuk, it’s not based on the region, or whether you’re in the East or West — it just depends on the city.

Kyiv attracts more people who are “different,” and not just in terms of their sexual orientations or gender identities. The bigger a city is, the more people with different perspectives it has, and the higher the level of tolerance and diversity, said Pokalchuk. But at the same time, it can’t be said that it’s always easy in the capital, harder in rural areas, and hardest of all in Western Ukraine for LGBT people. Just like it can’t be said that the LGBT rights situation in Ukraine was more dire ten years ago than it is today.

Produced with the support of Russian Language News Exchange

Translated by Sam Breazeale from Respond Crisis Translation