Urbanists, together with artists, came up with the idea of a memorial sign to commemorate the Beilis Case, the biggest trial in the history of the Ukrainian capital. Zaborona learned that the Kyiv city administration denied them permission to install this monument. The editor-in-chief of Zaborona Katerina Sergatskova spoke with Mendel Beilis’s grandson and found out that the 109 year-old story has not yet ended.

The virus of libel

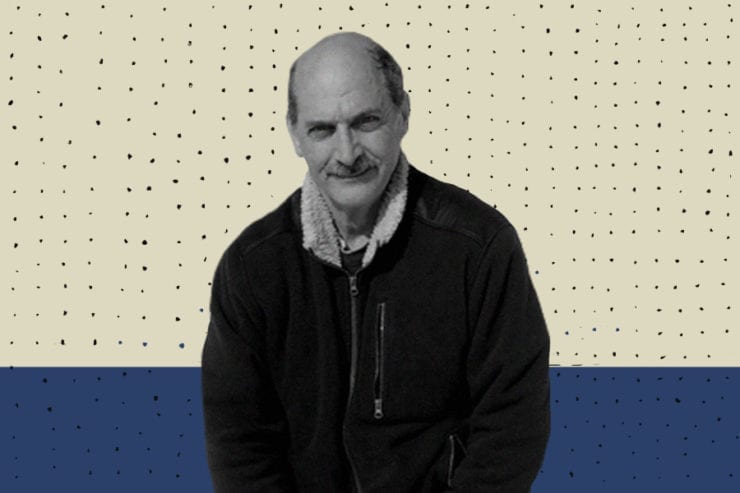

Jay Beilis is relaxing in a soft, comfortable chair on the veranda of his apartment in New Jersey. He is 67 years-old and he, along with his girlfriend, is strictly adhering to quarantine because of the coronavirus, which has already claimed the lives of thousands of people in America. “I’m at risk,” he explains.

Jay rarely goes to the store or out for a walk, and mostly sits at home. He watches the classics of cinema, which are shown on cable, and posts his reactions to films on Twitter, where hundreds of the same viewers discuss cinema. Not that he had nothing to do at his sixty-seven: he has a small garden, books, and old photographs that can be reviewed from time to time. It’s just that on Twitter, you can sometimes find news from Kyiv, the homeland of his grandfather.

At the end of 2019, the Ukrainian organization “Urban Curators”, which specializes in the development of public spaces, announced the name of the artist who would work on the creation of a memorial to the Beilis case — the most famous trial in Ukrainian history. The Beilis case is studied in Ukrainian schools and institutes. In terms of its significance for Ukrainian society and the world, it is on par with the Dreyfus Affair in France — when, using fake evidence, Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew, was accused of espionage on behalf of the German Empire, and spent 12 years in prison. At the center of the Beilis case is a small man who walked the rink of the corrupt and xenophobic system of the Russian Empire.

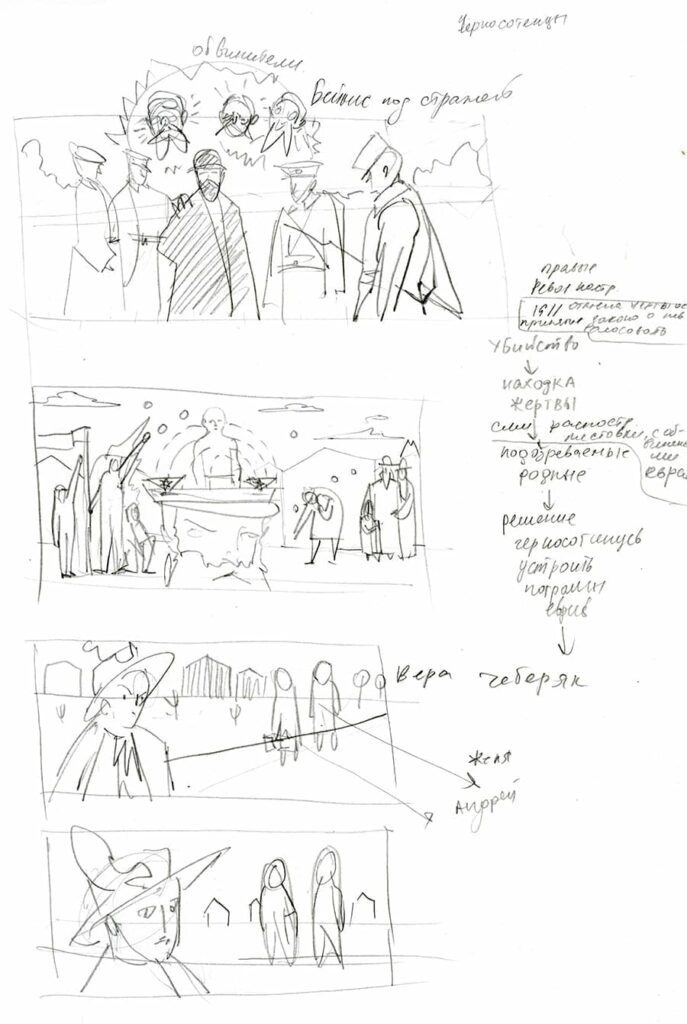

The 37-year-old Mendel Beilis was a Jew, lived in Lukyanivka area and served as a small clerk at a brick factory. He was unlucky to live near the house of Vera Cheberyak, who ran a thieves’ den and whose children loved to play with Andrei Yushchinsky, a 12-year-old teenager. In March 1911, Andryusha was killed, and the murder was hanged on Beilis, simply because he was a Jew. For two years he was tortured in prison, and in court, after pressure from public figures from around the world, he was acquitted. The real killers were not found and after the trial they did not reopen the case.

The Beilis affair became a symbol of shame for the police and judicial system of the Russian Empire. The trouble, according to the organizers of the “Urban Curators” competition, is that for a hundred-plus years little has changed.

The idea to create a memorial sign for the Beilis case belongs to the General Director of the Roshen confectionery factory, Vyacheslav Moskalevsky. This is not the first time he has been a patron of various projects. Moskalevsky financed the reconstruction of the Theater on Podil building, which still provokes strong debate. He bought the rights to publish the book “Babi Yar” by Anatoly Kuznetsov and installed in 2009 on Kurenevka a sculpture of a boy reading the announcement of the Nazi invaders, which demanded all Jews to come to Babi Yar with their belongings (about 100 thousand Jews were shot in Babi Yar after). Now, he wants a memorial sign to appear opposite the former building of the Pechersk courthouse, where Beilis was tried.

“They forgot about him [the Beilis Case],” said Moskalevsky. “Before Hitler appeared the most ardent anti-Semites were the [royal] Romanov family. It’s just that the German fascists, when they began to build concentration camps, surpassed them.”

How Andryusha Yushchinsky was killed

At 6 a.m. on March 12, 1911, Andrei Yushchinsky had borsch for breakfast and left the house. He lived on Slobodka, where the metro station Levoberezhnaya is now, and studied at the Kyiv-Sofia Theological College in the center of Kyiv. This school has produced many celebrities: such as Ivan Sikorsky, the father of aircraft designer Igor Sikorsky, a child psychiatrist and an ardent anti-Semite. In 1913, he would become one of Baileys’s prosecutors in court.

Andryusha Yushchinsky was the illegitimate son of Alexandra Yushchinsky, a seller of fruits and vegetables, and the tradesman Theodosius Chirkov. He left her when the child was very young, and was not involved in his upbringing. Spring began, and he didn’t want to study — and instead of going to school, he ran off to play with his friend Zhenya Cheberyak near the Berner estate on Yurkovitsa, then the outskirts of Kyiv (a hill on the way from Lukyanovka to Podil). Together with him and other boys from the district, Yushchinsky liked to play in the Zaitsevsky brick factory. The boys would harness themselves into the circular shaft meant for horses to mash clay and they would run and laugh. So they later described their leisure time to investigators.

It was Saturday, Shabbat. On Shabbat, Jews do not work and do not leave the house on business. Mendel Beilis was not religious. He lived on Verkhneyurkovskaya street with his wife Esther and their five children. He worked as a small clerk of a brick factory for the Jewish Zaitsev family.

The plant was not far from his house, on the site of the ancient Kirillovsky parking lot dug up for brick production. A couple of decades before the events, the legendary archaeologist Vincent Khvoika discovered the remains of mammoths there, at a depth of alumina. The destruction of this ancient monument for the needs of a Jewish enterprise then caused a lot of indignation among the people of Kyiv.

On that cool March day, wrote the press, Beilis stabbed Andryusha 47 times, drained his blood (the result would be five bottles) and presented it to the Hasidim to prepare matzo for the upcoming Jewish Passover. It was necessary to cook matza, they wrote in the press, with the blood of a Christian child. Beilis was alleged to have tied up the boy’s bloodless body and carried it to one of the caves behind Berner’s estate, where it was discovered a week later by children.

Investigators who described the scene of the crime said that the murdered boy was found in a sitting position, wearing only underwear and a single stocking. Nearby lay his jacket, sash, cap and folded notebooks. In the pocket of the jacket, investigators found a piece of a pillowcase with traces of sperm on it — it, they said, had been used to shut the boy’s mouth. An autopsy later showed that Andryusha Yushchinsky had been killed only three to four hours after he left the house — that is, almost immediately after reaching his friends at Lukyanovka.

Anti-Jewish court

At first, the investigators considered the possibility that the child was killed by thieves who often visited Vera Cheberyak’s den on Nagornaya, so that he wouldn’t tell the police that Cheberyak had been buying up stolen goods. One of the witnesses, her friend, claimed that the murder of Yushchinsky was “blamed on the Jews” in order to cause pogroms, “during which one could make a profit”. The criminal version of the story was quickly buried, and the murder was called a ritual and hanged on the Jewish Beilis.

The fact is, says the Holocaust researcher and historian Andriy Rukkas, that at the beginning of 1911, when the murder occurred, the State Duma of Tsarist Russia had been discussing a bill to lift restrictions on Jews, including the southwestern provinces. This meant that the Jews would be allowed to settle freely anywhere in the Russian Empire, whereas earlier it was possible to live only in the Pale of Settlement. In addition, the Duma had been considering the question of abolishing a zemstvo in the Western Territory — which would give Jews the right to vote and seriously change the political landscape.

“At first, the investigators went along with the the version that the murder was a commonplace crime,” says Rukkas. “But the matter was taken over by the Minister of Justice of the Russian Empire, a staunch anti-Semite, and the head of the Department of the Ministry of Justice came to Kyiv from St. Petersburg, who actually gave investigators instructions on which version to develop. The prosecutor who was involved in the case was also an anti-Semite. And all this was obviously agreed upon with the Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin. Perhaps even the tsar had initiated such an investigation”.

On April 15, 1911, a meeting of the black-hundredists organization “Union of the Russian People” took place in Kyiv, at which they made a decision “to step up measures to accuse Jews of the murder of Yushchinsky,” that is, pogroms. A few days later, the right-wing faction of the State Duma appealed to the Ministry of Justice and the Ministry of Internal Affairs with a request to pay attention to the allegedly ritual murder of a child in Kyiv. The case fell into the hands of the prosecutor Georgy Chaplinsky. He did not hide his friendship with the leader of another extreme right anti-Semitic organization, the Two-Headed Eagle, Vladimir Golubev — and allowed him to influence the investigation. It was Golubev who asserted the ritualistic nature of the murder of Yushchinsky by Beilis and the “Hasidic sect,” which killed Christian babies for the sake of making matzo.

“Key people in the then-Russian government were afraid that Jews would occupy key places in self-organized communities, so they needed an argument to stop these laws from passing,” says historian Rukkas. “If not for this murder, they would have found another. If it had not been Beilis, they would have found another Jew. ”

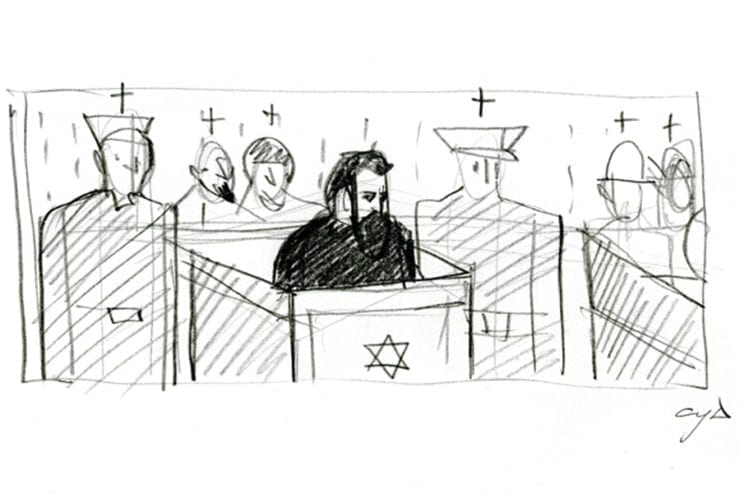

A verbatim record from the Beilis trial shows how electrified Kyiv society was by the murder in the fall of 1913. Deputies, ministers, renowned doctors, churchmen, black-hundredists, petty merchants and lamplighters, who not only addressed the Pechersk court, but tried to prove that a small clerk of a brick factory in the interests of the “Hasidic sect” had killed a Christian child in broad daylight. At the same time, he was defended by authoritative lawyers, such as Vasily Maklakov, who soon after the trial became the ambassador of Russia to France. For Beilis, democratic politicians, popular writers from Vladimir Korolenko to Vladimir Nabokov, also stood up in his defense. They tried to convince the jury, the Christians — as to the selection of peasants and merchants from the village — of Beilis’ innocence. There was no evidence against the Jew, except for the fuzzy oral testimony of a couple people.

The case quickly fell apart in court, and even the Black Hundreds, an ultra-nationalist movement who had pointed to the investigation against Beilis, doubted his guilt and accused the police of corruption and lack of professionalism.

On Monday, October 28, the jury was to announce the verdict. “Here the bailiff began to fuss … Here the audience tumbled down … They brought Beilis, for the last time there, from behind bars, into the dock. He was as pale as death, agitated, but kept his composure … ”, the writer Vladimir Bonch-Bruevich, who was present at the trial, described the moment.

The jury acknowledged that the killing was ritual, but it was not Beilis who had committed it. And who had committed it was unclear. Andryusha Yushchinsky’s murder remained unsolved.

A bus stop that wouldn’t be

Anya Zvyagintseva, a participant in the art groups “Khudrada” won the “Urban Creators” competition to create a memorial sign. She chose the form of a bus stop for the Beilis Case and proposed to install it opposite the former building of the Pechersk court, where the main department of the National Police is now located, on Vladimirskaya. The stop, the artist said, should be done with elements of the kind of judicial cage which suspects are placed in during hearings. Such cells have not been used for a long time in most European cities, but in Ukraine, as well as throughout the former USSR, they still exist, even though they violate the presumption of innocence.

“It was important for me to show the problem of the presumption of innocence,” says Zvyagintseva. “A person who is waiting for transport sits on a cube behind bars and becomes the central object, while the rest — all those who are waiting for transport — look. So he becomes a suspect, condemned. But there is no roof over this cell, just as there are thousands of people [who are not protected] from the system who must prove their innocence in our courts.”

Zvyagintseva also proposed to place a stand with information on details of the case and on the Roma pogroms that had occurred in Kyiv at least three times in the last 2 years (Zaborona talked about the pogroms here, here and here).

The idea of such a memorial sign didn’t “go well” with Kyiv city hall. “Each city stop has a specific number, they are entered in the register,” says Anastasia Ponomareva, coordinator of “Urban Curators”. “To replace the stop with a commemorative sign in the form of a stop, you need to go through the many circles of bureaucracy.” Anastasia went through these circles, but was refused.

The fact is that the municipal company Kyivpastrans is responsible for public transportation in Kiev. By law, only Kyivpastrans can initiate the installation of a commemorative sign at the stopping place, and must continue to maintain it with money from the city budget. “Alas, the duties of public officials does not include working with culture and memory,” says Ponomareva. “If they take the object on balance, they will be required to monitor it, bear responsibility for it, and people have low motivation.”

On February 24th of this year, Kievpastrans sent a short letter to Moskalevsky’s office: “The utility company, regarding your proposal to replace the waiting pavilion with the installation of a memorial sign with information about the M. Beilis case, objects to the execution of such work.”

Flowers on the grave of Yushchinsky

Podil still keeps traces of the story that happened more than a hundred years ago. There is Berner’s mansion on Nagornaya 14, an abandoned one. There are the pipes of the Zaitsevsky brick factory — they can be clearly seen from Yurkovitsa. And under the mountain, on Kirillovskaya, 59–61, — the building of Jewish surgery, which belonged to the plant. Now located there is the management office of the Farmak company.

If you continue on the Boguslavsky descent, you can find yourself in the same place where the Cheberyak children and Andryusha Yushchinsky once played. Only at the place where clay was mined at the beginning of the 20th century, a motor depot fenced with a high fence spreads out. Somewhere there is the cave in which the body of the tortured schoolboy was discovered. Or maybe in the decades since it collapsed and went underground.

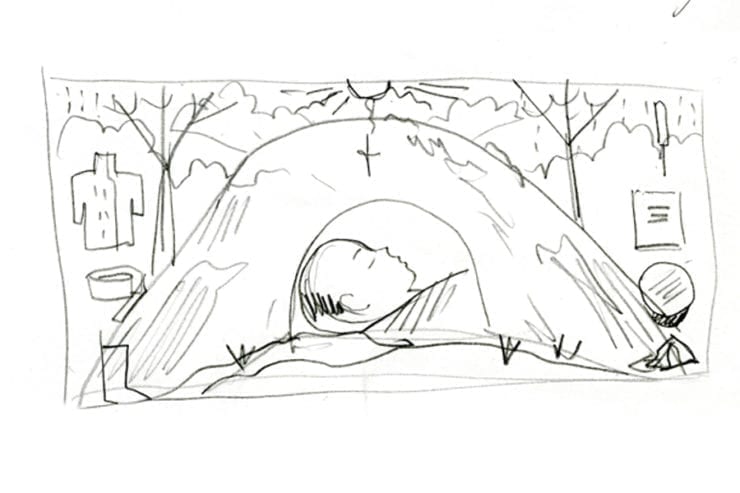

On Sundays, fresh flowers can be seen on the grave of Andryusha Yushchinsky, at the honorable Lukyanovsky Memorial Cemetery Reserve. Someone brings them after the liturgy in the Cathedral of the Great Martyr Katerina (which stands right there, in the cemetery). Yushchinsky’s grave is not like the others: there is a roof above it with a cross on top, a path is trodden, a grave lamp and several icons depicting the executed Romanov family are standing at the grave. On the cross is a tablet that says: “Here the relics of the holy adolescent-martyr are resting.”

“No Orthodox organization officially recognizes Yushchinsky as a saint,” says the historian Andrei Rukkas. “But there are sects who consider him a saint. 20–30 people in all of Ukraine, at most. These are the same sects, roughly speaking, that recognize Stalin as a saint. But today they adhere to the version of those times [about the ritual murder of Yushchinsky by Hasidists] only in anti-Semitic circles or in ultra-orthodox sects.”

At the beginning of 2004, unidentified men made their way to the cemetery and attached a metal plate to the cross with the inscription: “Andrei Yushchinsky, tormented by the Jews in 1911.” When this became known, the tablet was removed. And after 2 years, a white stone slab appeared on the grave. A quote from a jury verdict is carved on it, although Bailey is not mentioned, it is emphasized that the murder took place near a factory owned by a Jew.

“People often come to Yushchinsky’s grave,” says Oksana Borisyuk, head of the Monument Preservation and Preservation Department at the Lukyanovsky Memorial Reserve. “We are not usually asking them who they are. Usually these are closed, silent people … “

Perhaps the grave is looked after by members of the Union of the Russian People, the current reincarnation of the Black-Hundred extremist organization of the early 20th century, which tried to organize Jewish pogroms during the investigation of the Beilis case. The organization re-appeared in 2005, a hundred years after its creation under Tsarist Russia.

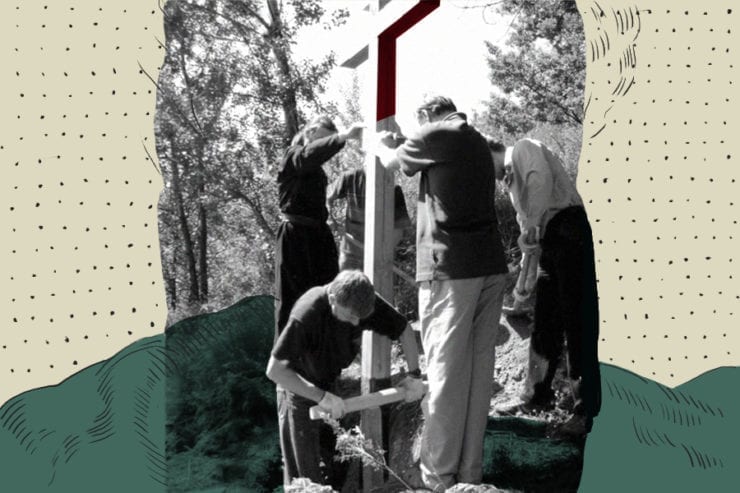

The Union of the Russian People calls Kyiv “the provincial department” and periodically holds its “religious processions” there, where they perform the hymn of imperial Russia “God Save the Tsar”. And on the anniversary of the trial of Beilis, in the fall of 2018, members of the organization established an Orthodox cross near the place where Yushchinsky was killed. In 2014, the Union of the Russian People endorsed Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and urged Igor Girkin-Strelkov to “restore Tsarist Holy Rus.” Supporters of the ideas of the organization include the former “Crimean prosecutor” and State Duma deputy Natalya Poklonskaya.

History stretches from the early spring of 1911 to today. 109 years later, Roma pogroms and anti-Semitic attacks occur in Ukraine. In Russia, as before, monarchism is developing and dictatorship is being strengthened, repression of Crimean Tatars and Ukrainians takes place in the occupied Crimea and the Donbas. Like a hundred years ago, people in the interests of politicians unfoundedly accuse each other of ritual killings — it’s enough to recall the Russian fake about the “crucified boy” in the spring of 2014 at the height of the war in Slovyansk. But the police and the courts still take bribes and imprison the innocent — in the interests of those who have concentrated power in their hands.

Jay Beilis’ Samovar

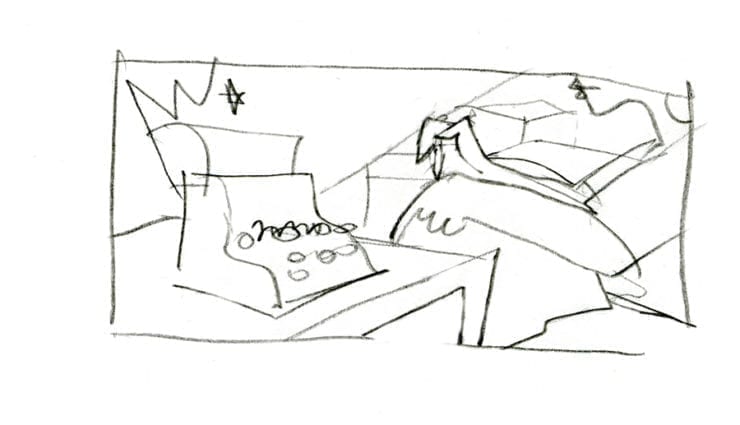

Jay Baileys keeps a samovar in his kitchen. The samovar “egg”, as collectors call this form, was made at the factory of Ivan Mikhailovich Batashev in Tula at the end of the 19th century and exported to Europe. The samovar is the only tangible reminder of the history of a hundred years ago: it was presented to Jay’s grandfather in 1913.

“After his acquittal, my grandfather could not stay in Kyiv,” Jay says.

At first, many celebrities came to Mendel Beilis, journalists and writers stormed his house — he became a star. But despite the sudden fame, continuing to live in Kyiv was dangerous: the Black Hundreds still believed in a Zionist conspiracy and ritual killings. The prospect of new pogroms loomed. At the end of 1913, he and his wife Esther gathered their five children and went to the “holy land”, in Ottoman Palestine, which later became the territory of Israel. They traveled through the Austro-Hungarian Empire, stayed in Vienna. Somewhere along the way, says Jay, Mendel Beilis received a samovar as a gift from a wealthy businessman as a gesture of gratitude for what he had had to endure in Kyiv. The Beilis case, his grandson says, prompted many Jews to emigrate from the Russian Empire, and thus spared them of the Holocaust later in the 1940s.

The samovar, along with its new owner, has come a long way before being in the kitchen of an American apartment. The Beilis family lived in Italy for a month, before arriving in Haifa. For about seven years they were engaged in agriculture in Petah Tikva, and in 1921 they moved to New York.

Jay still worries about the sad fate of Mendel Baylis. In some ways, he is very similar to his grandfather: a strict look, a sharp nose, a thick mustache, wrapped with the tips down. He was born 20 years after his famous grandfather died.

“Like all Jewish families after the Holocaust, people who were forced to flee to America talked about pogroms and persecution,” he says. “50 years after the trial, those who knew this story were still alive, including my father. I was small and wondered: who were these people that would come to our house and talk with my father about some kind of court? I was about ten to eleven years old when I found out about this story — about the age at which Yushchinsky was killed.”

Growing up, Jay became more and more interested in his grandfather’s story. He read his grandfather’s memoirs, which he wrote immediately after arriving in America, and published them in English in 2011, on the anniversary of the murder of Andryusha Yushchinsky. For the past couple of decades, Jay has devoted his life to spreading the memory of the most famous blood libel case against Jews in Tsarist Russia.

There are still no monuments in the world dedicated to the Beilis case. Except, the grandson laments, for a small street in Petah Tikva. When he saw Anya Zvyagintseva’ sketches for the memorial sign, he first thought that they were photographs, that the monument already existed.

“My first thought was that they will definitely draw swastikas on it!” He says.

Jay Baileys tweeted a photo of his grandfather’s grave. On a marble slab in Yiddish is carved: “Here lies a holy man, the chosen one of the Israeli people…” Jay is the last of the Beilis’.

“I have devoted almost all my life to the memory of my grandfather and his trial,” says Beilis. “But there are still people who believe that my grandfather killed a Christian boy for his blood for Easter. It is as if for over a century, humanity has not learned anything. ”

Translated from Ukrainian by Kate Garcia