Support Zaborona at this difficult time so that we can continue to inform you and record important stories.

Today’s full-scale invasion should be Ukraine’s last war with Russia, because if Crimea remains de-occupied, a new armed clash will begin precisely from the peninsula, according to Tamila Tasheva, the permanent representative of the President of Ukraine in Crimea. Until April 2022, she was the deputy of the former permanent representative Anton Korinevych, who currently deals with the international tribunal for Putin and Kremlin criminals.

A Crimean Tatar by origin, 36-year-old Tamila Tasheva, like many of her compatriots, was born far from her homeland — in Samarkand, Uzbekistan. In 1991, when Crimean Tatars were rehabilitated after deportation and returned to the peninsula, 5-year-old Tasheva and her family settled in Simferopol, where she lived and worked until the Russian occupation in 2014. Over the past 8 years, she rose from an activist and human rights defender to the head of the representation of the President of Ukraine in Crimea. Here she does what she does best: she defends the interests of Crimeans, both those who left the peninsula and those who are still under occupation.

Zaborona co-founder Kateryna Sergatskova met with Tamila Tasheva in Kyiv to talk about the role of Crimea in the current war, the scenario of de-occupation of the peninsula, as well as the punishment of collaborators in Crimea, and the future of the bridge across the Kerch Strait.

When a full-scale war began, along with the tragedy came the hope that this would be the last war with Russia, that we would be able to return Crimea. What is the current position of the president and yours — as the president’s representative — regarding the de-occupation of Crimea?

-

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin/ Zaborona

Both the president and the permanent representation of the president of Ukraine in Crimea have a clear position: we should de-occupy all the territories. There have never been any compromises on territorial integrity and there can never be. I absolutely agree that this should be the last war. If we do not return the territory of Crimea, then at any moment a new invasion from the peninsula may begin. Even after this hot period ends, even when we return the newly occupied territories. We clearly understand this, because we saw the terrible role of Crimea in this full-scale war.

By the way, have you seen these videos of Ukrainian territories being fired from Sevastopol?

People write to us, in particular from Sevastopol: “I am very sorry, although it is not my fault, but the first, second, third, fourth missiles flew from Sevastopol.” One of the last major shellings in Vinnytsia came from the Black Sea, from Sevastopol [on July 14, Russia hit Victory Square with missiles, killing 26 people]. Therefore, we understand that Crimea is a huge military base that has been created over 8 years. The Russians said that the Kerch bridge and the Tavrida highway [Kerch—Sevastopol—Simferopol road] were built for the civilian population. But today it is actually used for the rapid transfer of troops and equipment. Crimea today plays the role of a military, rear-guard, and raw material base for Russia.

You were always in favor of preserving human rights, for everything to happen gradually and carefully. After the invasion, theses about de-occupation, including the military intrusion, sound very clearly today. If you can imagine this picture, how will the de-occupation happen?

We have visited the United States recently — already after a full-scale invasion — and as representatives of the former human rights community, we always ask about weapons for Ukraine. I have a clear conviction: if we do not protect Ukraine as a state, no human rights will need to be protected, because there will be no people.

As for Crimea, last year we approved the de-occupation and reintegration strategy. The political and diplomatic way of returning the territories is clearly indicated as a key element. But there are other tools. As we write in the strategy: “using various asymmetric measures.” Of course, this is both a political and diplomatic way and the involvement of certain military elements.

I am sure that the military will be the first to enter Crimea. It is logical. Of course, we understand that now it is impossible to deploy an additional front and actually carry out a counterattack on the territory of the Crimean Peninsula. It is necessary to look realistically. But we understand that the end of the new phase of the war is directly related to Crimea and the return of territories. All our citizens with whom we communicate on the territory of the peninsula, as well as many experts, say that now is the moment when we must take back the territory of the peninsula, using different approaches. Primarily political and diplomatic, but not only these. According to international law, no one forbids us to regain the territory, including by military means.

Is there support from Ukraine’s partner countries for the de-occupation of Crimea?

It definitely is. The majority of partners stand on the position of non-recognition of the annexation of Crimea. A number of experts, who may have some pro-Russian sympathies, sometimes promote the idea that Ukraine should compromise. But the main partners, and primarily Ukraine itself, have a clear position: we will not compromise.

What has been happening after February 24 — the atrocities in Mariupol, Irpin, and Bucha — gives us the absolute right (although we had the right even before that) to stand on a clear position: no compromises, no negotiations on concessions and, [in particular], territorial concessions.

Let’s imagine that the Russians withdraw their troops from the territories occupied after February 24. The question of Crimea arises, and the swing begins. Ukraine wants to carry out the de-occupation, and Russia does not want to give up Crimea. What are the possible scenarios? Does the joint management of Crimea by Ukraine, Russia, and Turkey sound like a realistic option? How do you feel about it?

I have a negative attitude — we have to return the territories without any concessions. This is our right.

It is very important to talk not only about the territory but also about the people who live there. I cannot imagine the Russian Federation, which under the current configuration and political regime, would not violate basic human rights. What they have been doing in Crimea, those crimes against people… I don’t think they will ever stop doing it during some kind of joint management and so on. I absolutely reject such ideas and they are not discussed in any way.

-

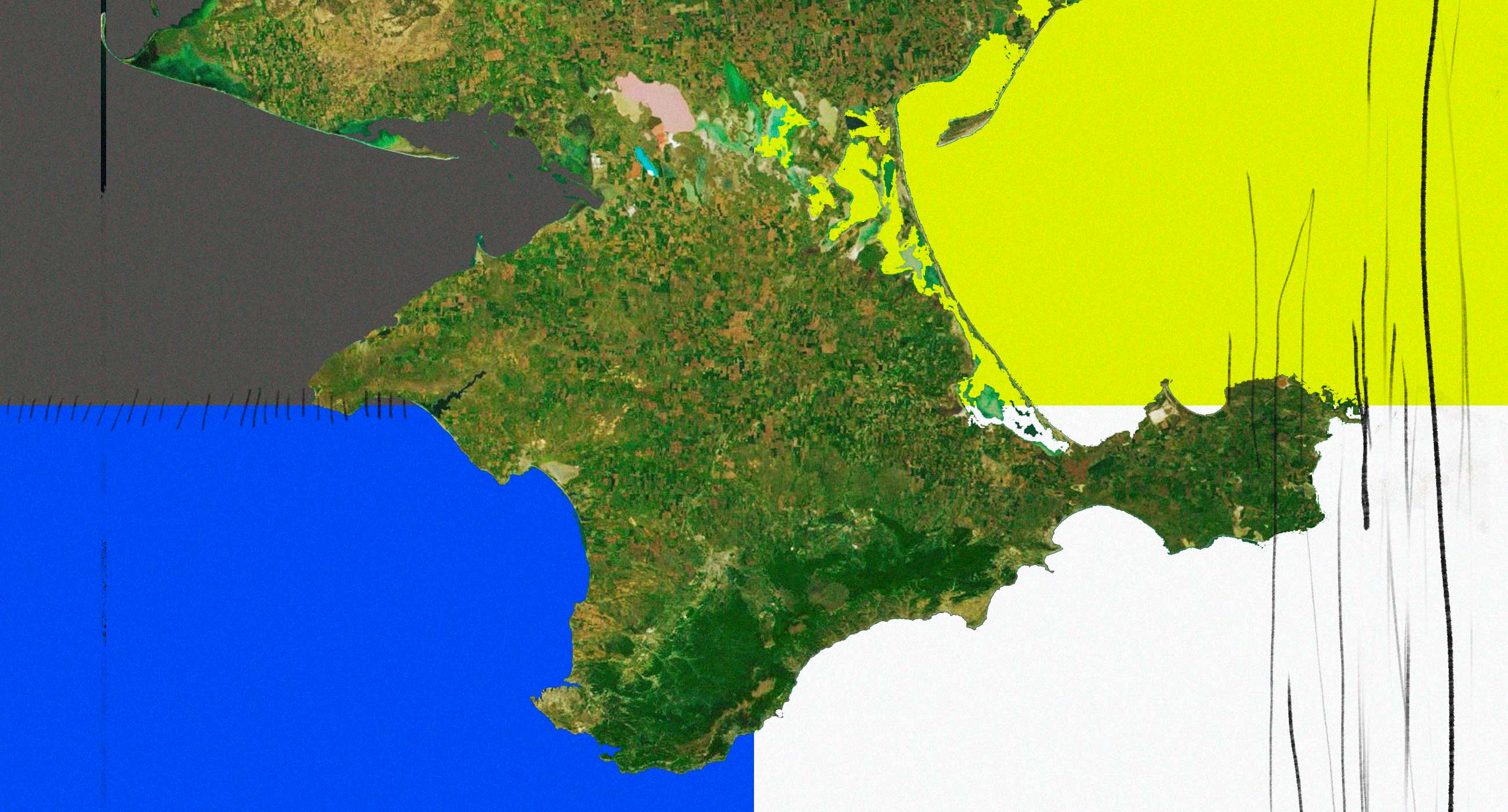

Collage: Mariya Petrova / Zaborona

Certain Russian politicians, of course, voiced such ideas or the option of holding a real referendum on the territory of Crimea. But here it is important to say that not only the 2014 referendum was absolutely illegal and was held at gunpoint. Now, any demonstrations of will on the territory of the peninsula are impossible due to the key reason — the Russian population there has increased by from half a million to 700 thousand people. This is the latest colonization of Crimea. Therefore, any referendums now are absolutely not representative — they will not correspond to the spirit of international law, and, of course, to the interests of the Ukrainian state.

Kherson region is occupied now. The representative office of the president in Crimea was once located there, and part of the population from Crimea moved to the Kherson region. What role did the Kherson region play for Crimeans and Crimea?

In 2014, the presidential representation [in Crimea] was relocated from Simferopol to Kherson. In 2019, the president made, in my opinion, a strategically important decision — to open a fully-formed office in Kyiv, while leaving the office in Kherson. Until February 24, we worked with two offices. The Kherson office dealt with people who had left the territory of Crimea and became internally displaced persons, or dealt with residents of the occupied territory who turned to us for services. The office in Kyiv dealt with more strategic issues, communication with international partners, with state institutions, in fact, with the president, the Verkhovna Rada.

A leap in legislation changes has taken place over the past few years. This is the de-occupation strategy that was adopted. This is the law on indigenous peoples, passed and submitted by the president. This is a strategy for the development of the Crimean Tatar language. The cancellation of the law on the free economic zone of Crimea, the opening of the National Office of the Crimean Platform, the Crimean Platform, etc. These were the right decisions and steps, which the Russian Federation also did not like very much.

Read Zaborona’s interview with the head of Crimean Platform Maria Tomak here.Are there any incidents of Crimean Tatars persecution in the Kherson region? Is the same happening there as in Crimea?

Yes. On the territory of the Kherson region, the entire activist field is being purged, both at the beginning of the occupation of the Kherson region and now. 70% of the population left the territory of Henichesk, where historically a large community of Crimean Tatars lived. Crimean Tatars have been persecuted very actively.

When the occupying forces entered the territory of the Kherson region, they already had “black lists” prepared. I think those had been passed on by some traitors. Now we know that the head of the Crimean branch of the SBU [located after 2014 in Kherson] Oleh Kulinich has gone over to the side of the enemy. He has already been accused of treason. The Kherson prosecutor’s office was partially infiltrated by Russian agents.

We understand where those lists could have come from.

I think locals could be involved in.

Locals could also report something, the Crimean FSB could form these lists.

When [the Russians] arrived, they started visiting the homes of Crimean Tatars who were related, for example, to the [representative body of the Crimean Tatars] Mejlis, or had taken part in the civil blockade of Crimea in 2015, or were the ATO veterans. In part, they [the occupiers] began to detain people and take them to the territory of Crimea. These people ended up in Sevastopol, Simferopol. Our internal sources reported that many people had been found in the Simferopol pre-trial detention center — these Crimean Tatars are accused of participating in the battalion named after Noman Chelebidzhikhan. They are being prosecuted because this battalion is recognized as a terrorist organization on the territory of the Russian Federation.

How do you feel when some politicians say: “Give these occupied territories to Russia, live on the remaining ones”?

It seems to me that most Ukrainian politicians do not allow themselves to do this, because they understand what will follow. Of course, there are a number of experts — French, German, American — I will not mention their names — who talk about concessions from Ukraine. We always understand what is meant by Crimea.

But we respond not only from the position of the territory but also from the position of values. The European Union was founded on the values of human rights, freedom, and democracy. When we are told to end the war faster, we always answer: “What about the people?”. People suffering in Crimea. People suffering in the territory of the Kherson region. Those who are persecuted, who have been in prison for 8 years, who were given 20—year terms. Without the liberation of the territories, these people will not be released. They will always be persecuted. They will be tortured. They will disappear like Ervin Ibragimov [a member of the executive committee of the World Congress of Crimean Tatars kidnapped in Bakhchisarai, whose whereabouts have been unknown for 6 years].

Are there partisans in Crimea?

Actually yes. We were often asked why there was no such resistance in Crimea [as today in the Kherson region] in 2014. I have a very clear answer: because in Crimea in 2014 there were no armed forces that could defend, there were no volunteers who could help, including our armed forces, displaced persons, and so on, there was no strong political power. Then it was basically absent. I remember how on February 26, [2014] there was an actual division of positions in the Verkhovna Rada [of Crimea], where they appointed the heads of the [pro—Russian] government. [In Crimea in 2014] there was actual anarchy, which the Russian Federation took advantage of.

Then the people in Crimea, who were ready to resist — even with armed resistance (although they did not have weapons for this) — realized that the authorities did not support them, and there were no soldiers. Most of the soldiers betrayed their oath and went over to the side of the enemy. The rest, not betraying the oath, were forced to leave for the mainland of Ukraine and continue their service here. They couldn’t resist on their own.

Crimea has been under occupation for 8 years. Absolutely everything was purged there: the media, activists… Everyone who could be imprisoned ended there, and Russian authorities continue to do so. It was surprising to me that [in 2022] there were people who started opposing the war and doing anti—war protests. We are following it. We know of 100+ cases of prosecution of such activists in courts. They are accused under the article about fakes against the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation. The people [who are persecuted] are completely different. There is an elderly woman who smeared the grave of a Russian soldier in her village with… let’s call it the products of human life.

How did you find out about it?

Through court registers. If I’m not mistaken, she was given 2 years [61—year—old Valeria Goldenberg from Sonyachna Dolyna near Sudak was sentenced to 2 years in a corrective colony].

Or activist Bohdan Ziza. He lived in the occupation for 8 years and did not support it from the very beginning. He is an artist, does parkour. When a [full—scale] war broke out, he poured yellow and blue paint and [threw] a Molotov cocktail at the Yevpatoria administration. Now he is in the pre—trial detention center, an independent lawyer is trying to break through to him, because he was also tortured, it can be seen on the video [after the detention].

There are many such people. Unfortunately, some of them are leaving Crimea, so we are losing activists who can resist. Some of them remain. We are actively communicating with those who have left — it is already safe for them.

That is, the representative of the president is really dealing with the partisans?

We do not deal with partisans. We communicate with people who resisted in Crimea, already after their departure to the territory controlled by [Ukraine] or abroad. We ask why they came [to the protest], what motivated them, and how many people like them are there.

It doesn’t look like a network — it’s mostly single people. [But they are] all over Crimea, even in small settlements — this is very important. Someone beat a Russian soldier — he has been held responsible for this. Someone refused to service a military vehicle at a service station. The owner of the service station then took full responsibility for this, because the entire occupation administration later knew about this incident. The station was closed, an inspection was sent to him and they said that the service station was located there illegally. People damage cars with the “Z” symbol: they break the windows, puncture the tires.

-

Collage: Mariya Petrova / Zaborona

Due to the military actions, due to the resistance taking place in Kherson, we may not notice this. The role of the presidential office is [in particular, to] tell about such stories, to show that there is resistance on the territory of the peninsula.

Russians in Crimea are most worried about their real estate — these houses, castles that they have appropriated or built. Is there a position on what will happen to this property after de—occupation?

Regarding the process of reintegration and de—occupation of the territory, I would speak in a broader context — we are already thinking about what will happen to Russian citizens who live illegally [in Crimea].

According to international humanitarian law, the Russian Federation or any country that occupied the territory has no right to resettle its citizens there. The latest colonization is taking place in Crimea today — from 500 to 700 thousand Russians have come there (we can roughly confirm these figures). Accordingly, they all came illegally. I know literally several people who are known to have entered the territory of Crimea under Ukrainian legislation — they asked for a permit for temporary residence in the territory of Ukraine, then documents for entry into the territory of the Crimean peninsula. That is, several Russian citizens who respect Ukrainian legislation live and work there.

All the rest entered the territory of Crimea illegally, accordingly, they must leave the territory of Ukraine after the de—occupation. This seems absolutely normal to me — it also does not contradict international law. Of course, we will not put these people in cargo trains, as was the case in 1944 [during deportation]. We do not act like the Russian Federation. But, if they violated the law, they must leave Crimea within a certain period. Then, if they really want to live on the territory of the peninsula — they were married there or their children were already born in Crimea — they can apply to the Ukrainian state for a temporary residence permit.

And if they have housing?

This applies to property. Any transactions on the territory of the peninsula are illegal. Any contracts are void. Only if such a deal was registered on the territory under the control of the Ukrainian government — and this could happen. For example, a Russian citizen bought a home/apartment from a Ukrainian citizen and registered it in accordance with Ukrainian legislation. However, the majority of such transactions were not registered under it. We currently do not have a ready answer — this is a big question on which experts are still arguing and working. As with the issue of lustration.

Lustration of collaborators?

Yes. This is a question of people who began to contribute to the establishment of the occupation regime on the territory of Crimea. Or those who, for example, did not violate human rights, but sat, conditionally, writing some numbers in the office of occupational authorities. Approaches to them should be formed.

Of course, if you betrayed the oath, there is already a question of criminal prosecution. And if you did not violate human rights, did not commit war crimes, then lustration means will be applied to you. That is, you will not be able to hold a position for a certain period. There was lustration in Poland, there was lustration in the Baltic countries. There is no need to invent anything new — just adapt it correctly, taking into account the experience of 8 years of occupation of Crimea. For someone, conditional amnesty will be applied.

There are many of them: the entire Crimean prosecutor’s office, the SBU, special services…

These are all people who, most likely, will be subject to criminal liability. I do not believe in an employee of the prosecutor’s office who simply translated some papers. Most likely, they committed crimes against human rights, war crimes.

-

Collage: Mariya Petrova / Zaborona

By the way, are there cases against them in the Crimean prosecutor’s office?

Yes. I don’t know the number of proceedings, the prosecutor’s office would rather say that. But there are many cases of treason, human rights violations, war crimes on the territory of the Crimean peninsula. In any case, this information is documented.

Ukraine works in different formats. One is personal sanctions against violators [including by the US]. The other is criminal prosecution. And a number of restrictive measures. But in Crimea, this should definitely be done already. We are currently working with MPs, the Ministry of Reintegration, and the Ministry of Justice, so that when we liberate the territory [of Crimea], the legislation is ready: on amnesty, on lustration, on transitional justice. Our framework is already set in the de—occupation strategy. But it is very important to continue working so that our citizens understand what they will definitely be responsible for and what they definitely won’t be responsible for.

How will Russia be responsible for Crimea? Reparations, etc. Do you see it as a separate process or a general one [taking into account the consequences of a full—scale invasion]?

General. Until February 24, the European Court of Human Rights and the International Criminal Court had separate cases on various violations regarding the [occupied] territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions and Crimea. There was a separate regulation for this in Ukraine. Now it will most likely be brought into line.

But according to international law, this was previously also considered separately. And although Ukraine has always insisted that the Russian Federation has control over the Donetsk and Luhansk regions, international partners have tried to avoid [the issue of] Russian military presence there. Now it is obvious to everyone.

In general, as a representative office, last year we made a study and a large report on the losses of the Ukrainian state. The losses are much greater now. Not all of them we were able to find, identify, and so on. Therefore, we are working with several other ministries to identify all this. When we will bill the Russian Federation for these crimes for 8 years, of course, reparations for Crimea will also be included.

What about the Crimeans who joined the ranks of the Russian army, now or until now? I understand that there are quite a few of them, as well as in Donetsk or Luhansk

This is a difficult question since there have already been 15 conscription campaigns on the territory of Crimea over 8 years. Every year they recruit about 5,000 people. These are more than 30,000 people [during 8 years of occupation]. Forced conscription is illegal under international law. They have no right to conscript Ukrainian citizens into the ranks of the Russian army, let alone send them to participate in combat operations.

Participating in the armed forces of the occupying country does not mean that you should be prosecuted under the criminal law of Ukraine — this is contrary to the IV Geneva Convention. But [this does not apply to] when you yourself started shelling civilian objects, killing civilians, committing other war crimes, etc. It is very difficult to identify such persons — in fact, proving their innocence may fall on a person who may or may not have committed these violations. There are very subtle points here.

There are quite a lot of conscripts who were sent to war during these months, as our military says. [Those who went to serve in the Russian army] in the fall of 2021 have already been noticed fighting in combat operations in Ukraine.

Is there already evidence that Crimeans are among them?

Yes, there is evidence. For example, sailors from Crimea died on the cruiser Moskva, which was sunk by our armed forces. Most likely, they can be identified as Ukrainian citizens if they lived there in 2014 and had Ukrainian citizenship. We know the tip of the iceberg — it’s what we have learned from public sources.

Manpower is illegally used in war. The position of the state [is]: if you can refuse to go to the war, try it in some way (it sounds bad from the mouth of the head of a state body, but…) bribe the occupation administration, hide in some way, change numbers, place of residence, etc., leave the territory of Crimea. If you have already been drafted and sent to combat operations, surrender at the first possible opportunity. There is no other way not to commit crimes in war.

There are cases when people surrender. I cannot say that we know about a large number of such persons, but we know about captured Crimeans. There will already be a question regarding an independent investigation in the court process, proof by prosecutors and investigators of their guilt or innocence. The position of the state is fairly balanced: if you committed a crime, you must be held accountable for it.

I have a theory about the invasion, it is related to the Crimean platform. It was quite loud, a bunch of representatives of European countries, America, and NATO came to Kyiv. Seven years after the occupation, we finally started talking about de—occupation, about what will happen to Crimea next. This also activated the Russian government — Putin expressed how much he disliked the Crimean Platform. Could he be so mad about it to go all—in on a full—scale invasion?

It seems to me that Putin and the entire leadership of the Kremlin went crazy a long time ago — even before Crimea, even before 2014. I partially agree, but only partially. Russia was preparing for a [full—scale] war even before there was no Crimean Platform. During the 8 years of occupation, they turned Crimea into a springboard for an offensive.

The Crimean platform could be one of the elements that prompted the launch [of a full—scale invasion] at the very moment. But I am sure that after 2014 they had no intention of stopping in Crimea and planned the actual destruction of Ukraine as a state. Ukraine, as a sovereign and independent state with its own plan and vision of development, European and Atlantic integration, has always bugged them.

For our part, we also had to do something in Crimea during all the years of occupation. I don’t like to speak badly of my predecessors, but there is a fact: the previous administration did nothing for Crimea. I think I have the right to speak like that — as a Crimean woman, as a person who has worked in human rights for almost 6 years. I know what was done and what was not done, what were the appeals to the MPs of the then convocation, to the president of the state at that time. That the law on the free economic zone of Crimea should be repealed. It was lobbied for in 2014 when the former heads of state had their own businesses on the peninsula — they worked legally on the territory of Crimea, without paying taxes to the state budget of Ukraine. When we said that it should be canceled, everything was done not to cancel it — I remember it very well.

-

Collage: Mariya Petrova / Zaborona

In the end, the de—occupation strategy [was not adopted either]. I was very embarrassed when I met with international partners (the US State Department, the European Commission) and they asked: “Well, Ms. Tamila, is there a strategy for returning of the state?”. I said: “No, there isn’t.” We have not seen any document. There was no vision of the state — only some sporadic actions, not synchronized with each other.

It started to move under President Zelensky. Yes, I am a representative of this particular president, and someone can say, they say, it is clear why she speaks positively about President Zelensky. But this is an objective reality when you understand what legislative acts have been adopted regarding Crimea. This did not happen during that period [during the tenure of Petro Poroshenko]. The fact that this became a trigger story for Putin is clear. But was this the main reason for the full—scale invasion? No. They have been planning it for 8 years, if not earlier.

What is your attitude to the physical integrity of the bridge across the Kerch Strait?

I cannot speak about this expertly, but here is what I can say: the Kerch bridge is used for military purposes very actively. Accordingly, if we talk about a purely military target, it should really be an object [for the attack].

But we should understand that there is not only a military component here but also a political one. We communicate with our partners who request and provide weapons for use in defensive and partly offensive activities. Of course, Crimea and Kerch are Ukraine. We can, in theory, use this [weapons provided by partners in the occupied territories]. But will we achieve our goal by destroying [the bridge across the Kerch Strait]? Of course, several experts, including representatives of state institutions, talk about the need to destroy [the bridge]. From a purely military point of view, I absolutely support it, because the supply of weapons, equipment, and military personnel is actively taking place through the Kerch Bridge. Of course, we could cut them off from that.

Will we achieve by this the de—occupation of Crimea, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia regions, and so on? I do not know.

When do you think we will be able to come to Crimea?

No one will say objectively — and it will also be true. Of course, we want this as soon as possible. We simply don’t understand when we will be able to de—occupy, in particular, the Kherson region, how long the hot phase of the war will last. Anyway, any wars in the world always end with negotiations with the signing of a peace treaty. Here, it is very important that this peace treaty and actually this victory, what it will look like, should be defined precisely from Kyiv and on the positions of Ukraine. We must clearly stand on the policy of non—recognition of annexation, on the position of our territorial integrity, the borders of 1991, and so on.

Will we be in Crimea? I have no doubt about it. I’m sure we will. Will it be tomorrow? Will it be in a year? This will already be decided, including during this second big war.