During the five months of the war, 63-year-old Leonid Struk from Chornobyl lost his sleep, his health, as well as his garage with his car, tools, and almost all documents. And if the Russians, who occupied the exclusion zone at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, were the ones who took his things, the locals are responseble for has garage’s destruction, the man claims. He says they set it on fire. Struk calls the exclusion zone a state within a state: there are special rules and the law not applying to everyone. Moreover, during the month of occupation, many people from Chornobyl started working for the Russians, and now they are taking revenge because he calls them collaborators.

“On February 24, I woke up from silence. There was such a horror silence in Chornobyl! I started the car’s engine , and drove around the city — there was no one there. I drove up to the administration of the exclusion zone office — it was closed. I drove up to the police — not a soul,” says Leonid Struk, lighting a cigarette with trembling hands.

Leonid Struk spent most of his life out of 63 years in the exclusion zone, in his parents’ house. In Chornobyl, he studied, worked at a nuclear power plant, and eventually retired. His last position was an engineer for the transportation of dangerous goods. He used to remove nuclear waste.

We are talking near the Institute of Radiology in Kyiv — due to his long-term residence within the exclusion zone, the man sometimes comes here for a medical examination. However, he never knows if he will be able to return home, especially now.

Two main groups of people live in the exclusion zone. There are so-called self-settlers — they are allowed through the checkpoint outside the zone and back because they have special passes. Another thing is that the local administration does not recognize those who live in the exclusion zone from a young age. For these people, any trip outside the exclusion zone may be the last, as there is a risk that the administration will not provide a return pass.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

So it happened with Leonid.

The man explains: the exclusion zone is a state within a state. It is not laws, but “their own” rules that apply here. Thus, in the exclusion zone, people engage in illegal deforestation, hunting, and fishing with the support of the local police.

Leonid smokes slowly, sometimes putting the cigarette down, then picking it up again. He recalls that at the beginning of the Russian invasion in February, he wondered why the bridges over the Prypiat River hadn’t been blown up, but only filled with blocks, while the bridge over the Vuzh River had been blasted up in half.

Leonid Struk. Photo: Vladyslav Musienko / Zaborona

“I am not a military person, not a tactician or a strategist — I don’t know why our military did this,” says Struk. “But around noon [February 24] I saw the first Russians. The “orcs” [that’s how a Ukrainian would call the Russian invaders — ed. notes] appeared right in front of me — I live near the Prypiat River, where there used to be a ferry crossing. I understood: they unblocked the bridge and continuously moved towards Kyiv.”

Occupation

For the first 3-4 days of the full-scale invasion, the Russians did not enter Chornobyl, but drove past it, Struk says. The town had both light and communication. Leonid saw the movement of enemy vehicles and transmitted data to the SBU using the phone number he had received from a fire department employee.

According to the man, more than 200 locals lived in the exclusion zone as of February 24. All others are zone workers. The fire brigade remained in full force and extinguished fires caused by shelling during the occupation. In addition, the employees of the medical units remained in place: all doctors, junior medical personnel, and nurses.

-

Damage and debris left by Russian soldiers at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant on May 28, 2022. Photo: Stringer/Getty Images

Leonid Struk remembers that when the Russians wanted to enter the houses and there was no one at home, they smashed the doors. They looked for goods. First, all alcohol and cigarettes were taken from the stores. And when they set up their command post in the town, rotations began: some went to Irpin, others robbed and searched people in Chornobyl.

Locals who remained in the zone helped each other in every possible way. An acquaintance of Leonid distributed food products left in warehouses: meat, cereals, flour, oil, and canned goods. So the locals had plenty of food. However, communications in the zone began to disappear as soon as the Russians occupied the Chornobyl nuclear power plant in nearby Prypiat.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Leonid knew that operational or maintenance personnel must have remained at the captured station, so one day he decided to try to get them out of there. But on the territory of the Chornobyl nuclear power plant, he was immediately met by an armed Russian soldier.

“I told him that I’m a local, I would like to take people out of there, at least women. There was not much food at the station, so I insisted that we, the locals, would feed the people and find them shelter,” Leonid recalls. “In 20 minutes, a 30-40-year-old Russian man in black clothes came out. He stated that all employees of the station had refused to go. But I know the procedures at the station: if something needs to be announced, they make an announcement over the loudspeaker, but no one announced anything. So I turned around and went home.”

After the communication was lost in the exclusion zone, it was possible to catch the network from only three points: upstairs near the church, in the park where the soldiers of the Second World War are buried, and on the fifth floor of the old boarding school. But you had to make a call because all incoming signals were muffled.

When the SBU employees, through whom Leonid transmitted information about the Russians, stopped contacting him, the man began calling the former Chornobyl prosecutor, who was in Slavutych. One day she said, “Men in black have come—perhaps their SOBR, looking for people.”

A few days later, Leonid met two cars with people in black by the river. He says they had a map of Chornobyl with all the streets and houses. They showed it to Leonid and asked where the police and SBU employees live. Leonid did not tell them. The cars had left.

Prisoners

On March 23, Leonid Struk came to his friend’s house and met two non-local guys there.

Before entering Chornobyl, 45-year-old Vadym Sydorenko and 32-year-old Rostyslav Patrin spent two days in a pit — the occupiers took the men prisoner in the villages of Ivankiv and Borodianka in the Kyiv region.

In a conversation with Zaborona, Vadym recalls: “Many people in the black uniforms appeared. As I understood it, it was SOBR — special forces that carried out the cleansing of territories. At first, they were looking for the Ukrainian Armed Forces, ATO veterans [the Ukrainian Veterans of the Donbas war in 2014 — ed. note]. Then they took everyone indiscriminately.”

The same fate befell Rostyslav. He and Vadym were saved by the fact that the Russians went to Chornobyl for rotation, where they abandoned all the prisoners.

“They said: ‘Live, dogs,'” Vadym recalls.

Struk and some locals were initially suspicious of the men, but it turned out that they had mutual acquaintances. Then Leonid decided to take Vadym and Rostyslav under his wing.

“He moved us, settled us in a house, promised that he would take us by boat to the village of Straholissya — from there we had to walk [to our native villages],” says Vadym about Leonid Struk. “And the next day, [three] locals came to us, and, to be honest, it was very scary. They were angry, they said that they live according to the Russians’ rules, so get out of here.”

According to Leonid, those men who came to the former prisoners cooperated with the military commandant of the Russians in captured Chornobyl. They told Struk that Vadym and Rostyslav were creating additional problems in the town, that the Russians would be looking for them, and because of this, they would not be kind to the locals. Those men eventually left, however, they promised that they would tell the occupiers about Vadym and Rostyslav.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

I looked at them and saw that they were like hunted animals. I cried because I didn’t understand why it was happening to them. Vadym also cried: “Uncle Lionya, every day here is a year of my mother’s life. She doesn’t know where I am. And I don’t know how to reach her,” recalls Struk.

However, the Russians did not return for Vadym and Rostyslav either the next day or a week later. At the end of March 2022, they were just about to withdraw troops from the exclusion zone — Leonid believes that then they did not want to search for prisoners. Already on April 1, they completely left Chornobyl, and before that, retreating, they had destroyed the bridge across the Prypiat River which was built at the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

On the same day, Vadym and Rostyslav said goodbye to Leonid, drove to the destroyed bridge, where they met the Ukrainian Armed Forces, and with their help got home.

“I didn’t think I would survive,” says Vadym. “When I returned, it was only a month later that my family and I were able to finally realize everything that had happened. When [the Russians] entered [Ivankiv], they considered us animals. This is an absolute genocide, none of them perceived us as human beings, they only spoke to us with obscenities.”

-

A room in the administrative building of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant, where the Russian occupiers have been holding National Guardsmen hostage since February 24. On March 31, during the exit from the Chornobyl NPP, the Russian occupiers took 169 National Guardsmen. According to station employees, before leaving, the occupiers looted the Chornobyl power plant and stole everything they thought was valuable, including teapots, coffee makers, computers, and 200 folding beds. Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant, April 22, 2022. Photo: Mykhailo Palinchak / SOPA Images / Getty Images

After the de-occupation

For Leonid Struk, the liberation of Chornobyl from the occupiers was only a continuation of his troubles. He says that after the de-occupation, he realized that evil is not inferior to good in terms of force — he saw it on the example of the locals.

“With the departure of the Russians, they [local residents] began looting little by little, stealing fuel and draining diesel,” he says.

When the senior precinct officer of Chornobyl came to Struk in early April, the man began to tell him about the locals who collaborated with the occupiers and wanted to hand over Vadym and Rostyslav. And within a few days, acquaintances from the management of the exclusion zone told Leonid that someone had written on Facebook that he “sheltered two orcs.”

Leonid Struk. Photo: Vladyslav Musienko / Zaborona

“I told the precinct officer about the looting by the locals,” says Leonid. “Perhaps the best defense is an offense. Everyone was afraid that they would have to answer [for collaborating with the occupiers], and decided that it would be easier to blame me.”

Struk says that he went to the local police with his testimony, where he openly stated in the presence of law enforcement officers that “if the police had patronized these thieves less, none of what happened during and after the occupation would have happened.” After these words, Leonid was advised to go to Kyiv — to the Department of Internal Security of the National Police. That is what he did and filed a statement regarding collaborationism in the exclusion zone against three residents of Chornobyl. But, returning from the capital on April 15, Struk could not get home.

Leonid Struk. Photo: Vladyslav Musienko / Zaborona

“There was a guy in uniform standing [at the checkpoint of the exclusion zone] and saying: ‘I have an order not to let you in,'” says Leonid.

To get into the zone, you need to have a special pass — Struk had one as a resident of the zone and a former employee of the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. The police at the checkpoint examine whether the pass is valid and then allow you to drive in. However, Leonid was not allowed to enter the zone. The reasons were not explained. So the man returned to the Department of Homeland Security.

“He said that they wouldn’t let me in. The DHS employees called someone, and I drove to the zone,” he explains.

But later the situation happened again. Leonid wrote a statement to the DHS, turned to the press center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine. After some time, according to the man, he received a call from the exclusion zone and promised that now he would definitely be able to drive home. Struk was indeed able to return to Chornobyl, but on the evening of the same day, he experienced another shock.

-

The Chornobyl nuclear power plant under the control of Ukrainian troops after the retreat of the occupiers, June 3, 2022. Photo: Raul Moreno/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

Fire

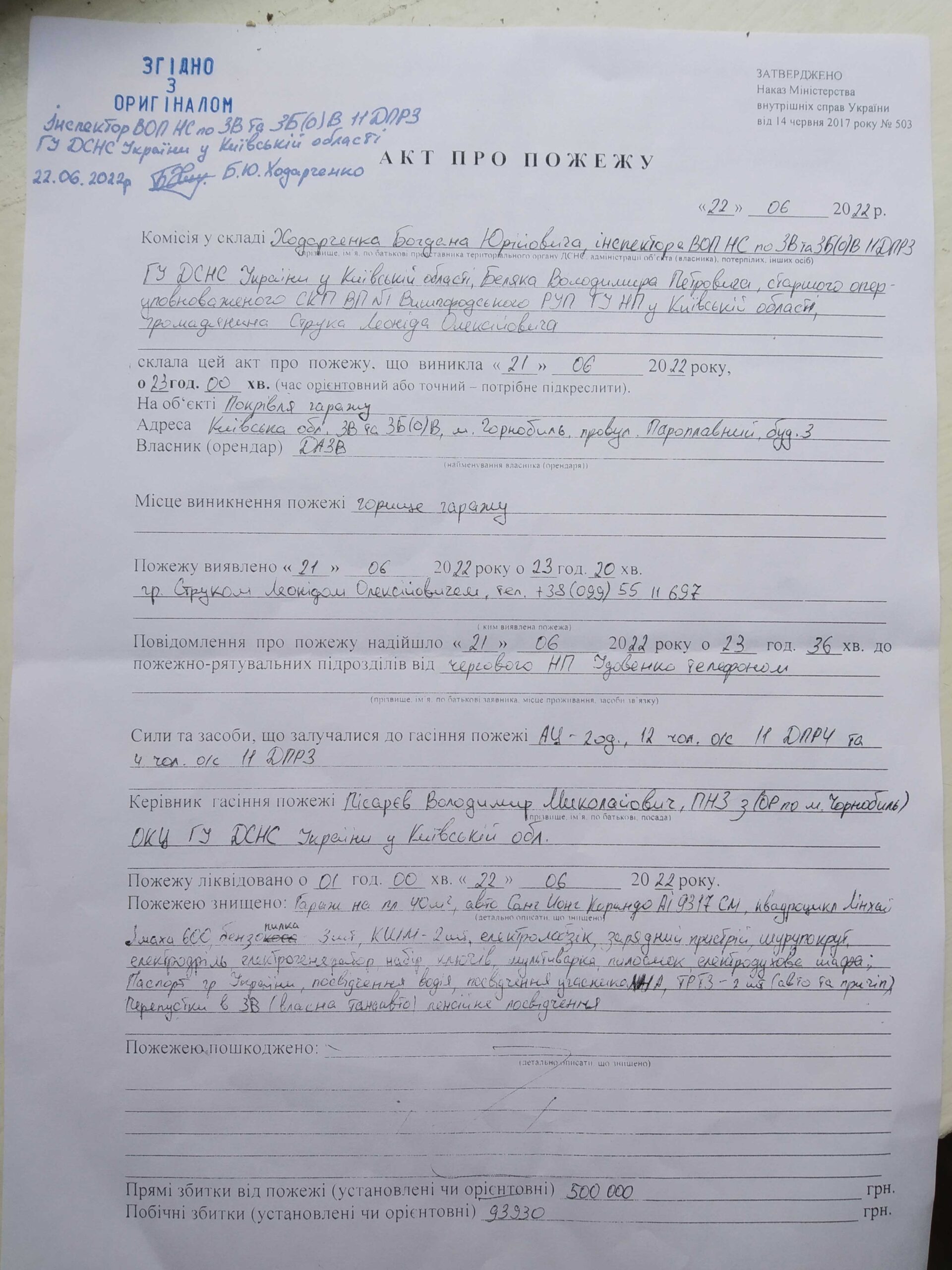

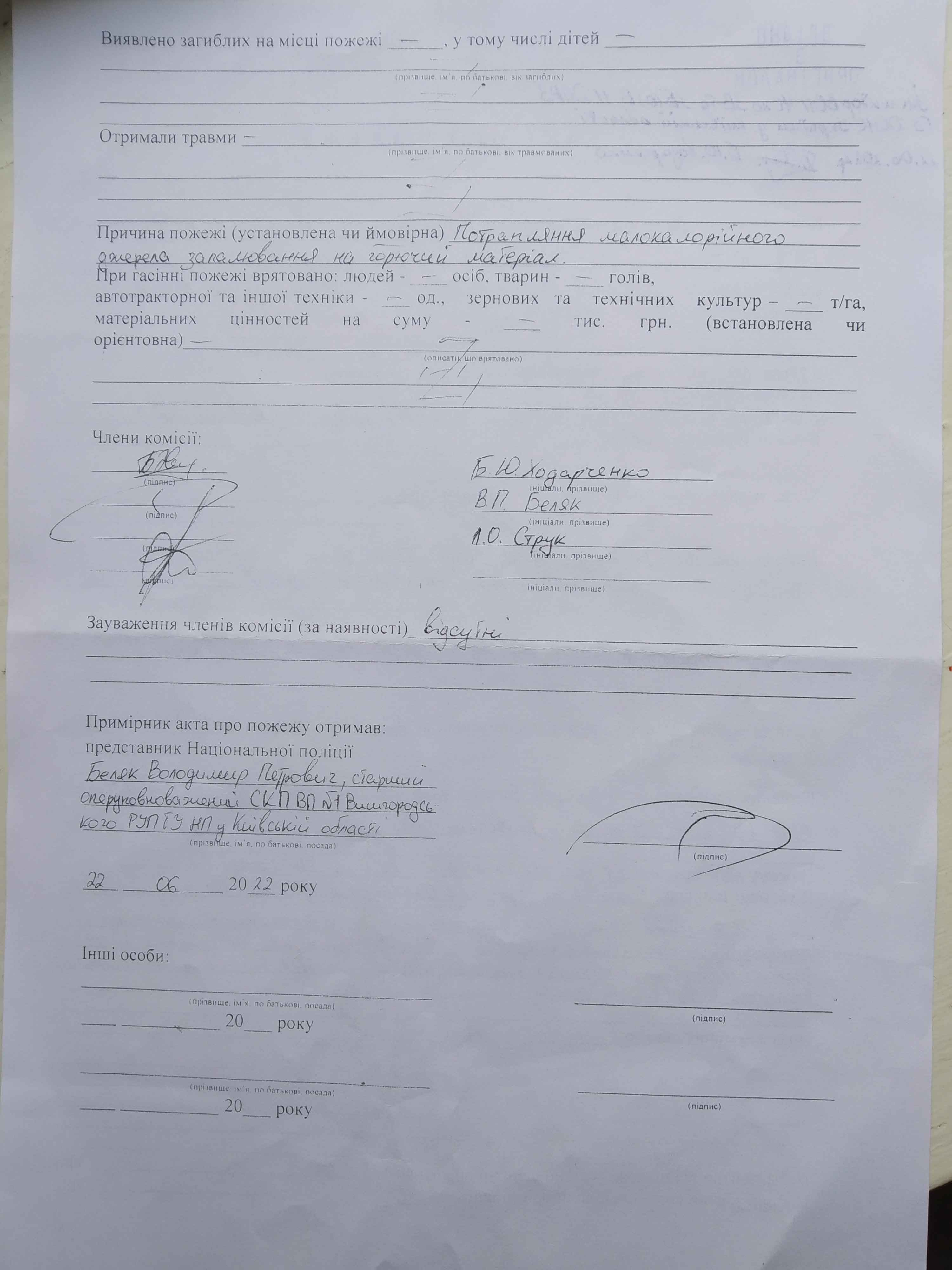

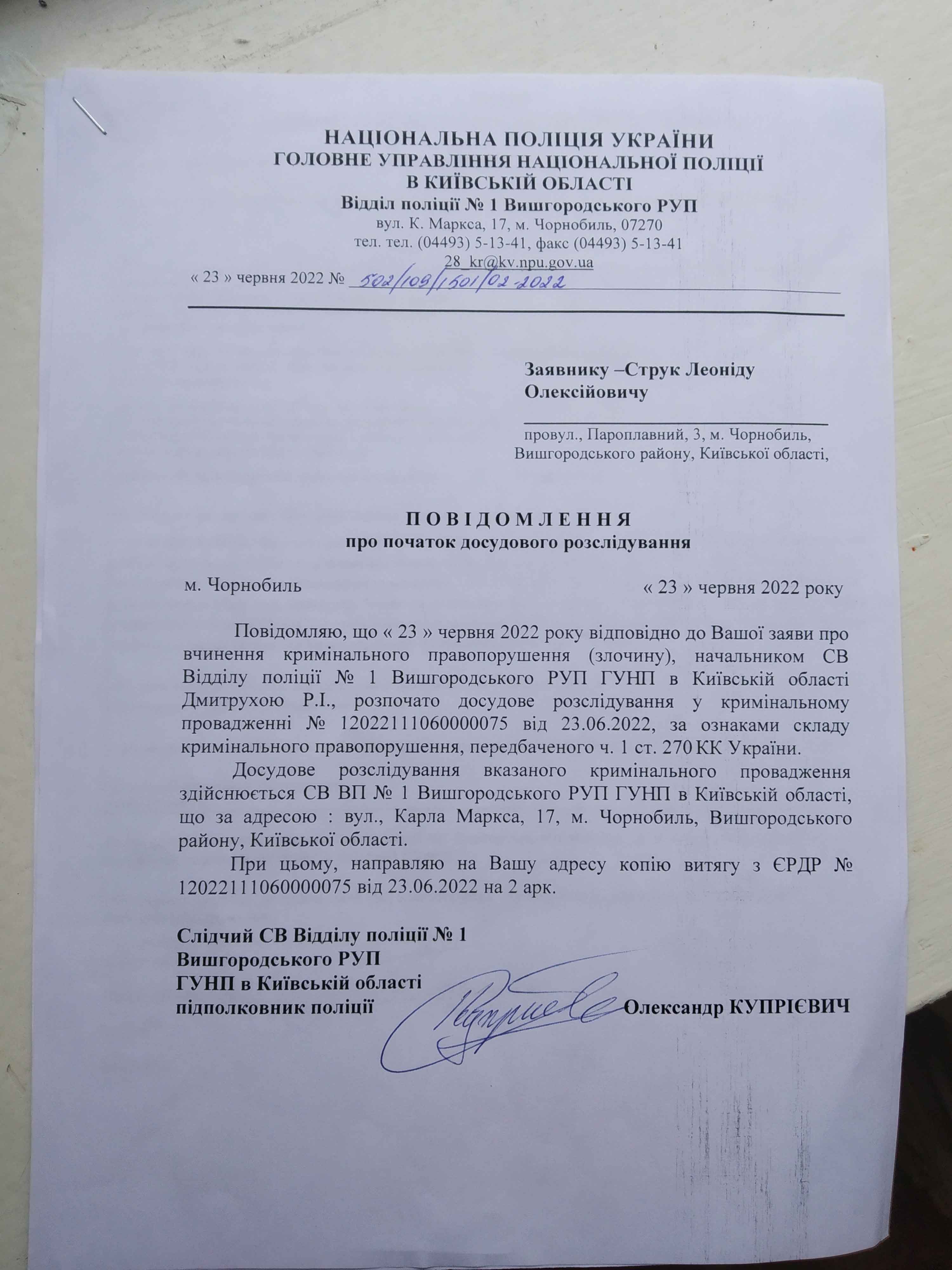

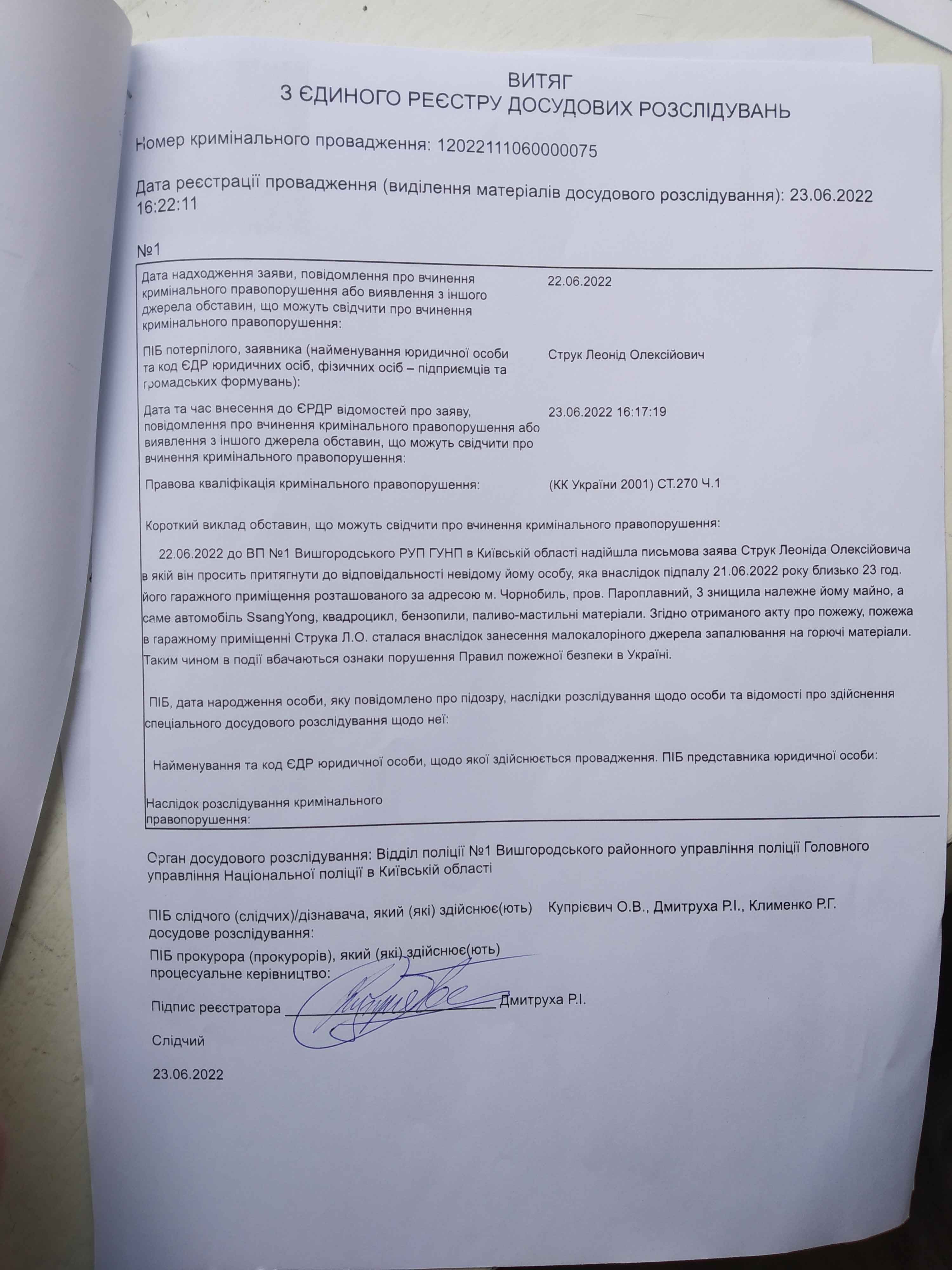

Leonid twirls the cigarette between his fingers. The man talks with tears in his voice about how the fire in the garage destroyed his car, tools, and almost all documents, including his passport and passes to the zone, within a few hours. In the police protocol, the cause of the fire was written as follows: “a low-calorie ignition source hit combustible material.” Simply put, someone set fire to the roof of the garage.

Illustration: Kateryna Kruhlyk / Zaborona

Struk is certain: the garage was deliberately set on fire. He considers it revenge for the fact that he openly talks about the collaborators in Chornobyl and those who, in his opinion, are patronizing them.

“I don’t have proof that it was the police or those three [who wanted to hand over Vadym and Rostyslav to the occupiers] who burned down my garage, but I think it was them,” says Leonid. “They could set arson at any time – I spent a week in Kyiv, but they did it right when I was at home. The inspector of the fire department said: the fire was organized professionally. The paradox is that the local police are investigating it themselves. I think they just want to show who is the boss here – and if someone says even a word to the police, it will happen to everyone.”

Vadym Sydorenko tells Zaborona that the SBU and NABU visited him and Rostyslav. The men were ready to take a lie detection test and confirm Leonid’s words about collaborators among Chornobyl residents. But there was no such test and almost nothing was asked about the people of Chornobyl. The workers were only interested in whether Vadym and Rostyslav were really detained by the Russians. According to Leonid, the case of collaborationism is not being investigated today, and man does not know what to do. All documents and copies of statements to the DHS and the National Police were burned in a fire [Zaborona appealed to these authorities to confirm the statements received from Leonid Struk, but so far has not received a response].

Photos of documents related to the arson, provided by Leonid

Photos of documents related to the arson, provided by Leonid

Photos of documents related to the arson, provided by Leonid

Photos of documents related to the arson, provided by Leonid

Struk looks thoughtfully at his hands and the cigarette butt. He offers to go to his ward – there are copies of documents about the damage caused by the fire. A man walks through the park, slowly shaking his head. He enters the hospital at the Institute of Radiology and strides bossily through the corridor maze.

Leonid Struk Photo: Vladyslav Musienko / Zaborona

“I understand: there is a war in Ukraine now, and what happened to me is a trifle. But it hurts me the most that my neighbors did it. And they did it so demonstratively, as if they were the masters here, like, what are you going to do to us?” Leonid says. “They will understand that the law here is not the one established by the state, but the one established by these police officers, for example. It will be like in Russia – a police state. I realized that our law enforcement system is no better than the Russian one.”

Now Leonid has a certificate to get to Chornobyl, but he is sure that he will not be allowed there again. Leonid has an apartment in Slavutych, so he plans to go there after being discharged from the hospital. However, he regrets that he cannot return to his family home.

“I don’t need anything anymore, the only request is to live until I die on my land, to be buried next to my parents,” he says. “I don’t know how much time is left for me in this world, but I follow two rules: to tell the truth and to do good deeds. If at least every third person does not live by this principle, then we will have nothing. After our victory, Ukraine will have the most terrible enemy, with whom, if we do not fight, we will become worse than Russia. This is corruption. It is my – and our – duty to children and grandchildren to fight this evil.”