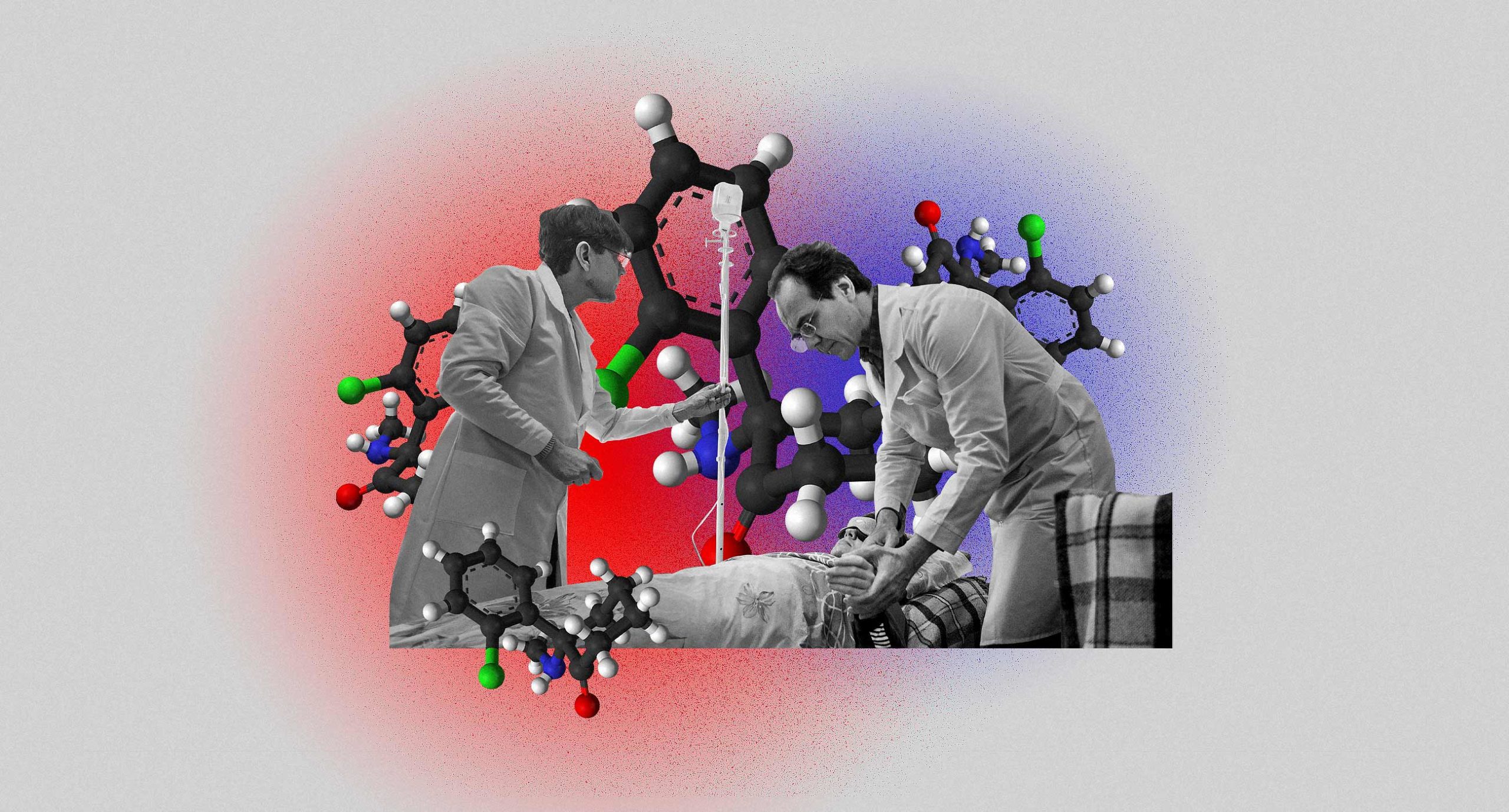

Since the 1970s, therapists and psychologists have experimented with using psychoactive drugs like psilocybin, cannabis, MDMA, and microdoses of LSD to treat mental disorders. Psychoactive drugs are banned in Ukraine — with the exception of ketamine, which has been shown to have a relieving effect on the symptoms of depression. Ketamine also happens to be produced in Kyiv, the home of Eastern Europe’s first ketamine therapy clinic, Expio. Lisa Moroz reports on what ketamine therapy is, how it works, whether it’s actually effective.

Two years ago, 40-year-old Anna (whose name has been changed at her request) began experiencing depression: she started to cry every day, she couldn’t get out of bed, and she wasn’t able to go to work. She could tell the depression stemmed from a combination of both professional burnout and the stress she experienced as a result of her son’s health problems, so Anna decided to see a therapist to talk about the issues.

Over the next year and a half, she experienced significant changes thanks to therapy. Eventually, she quit her job, and her son moved into a different apartment. The depression went away.

“In general terms, everything was okay. But I didn’t feel happy. I tried a number of things: diving, surfing, a new job. But everything seemed meaningless,” said Anna.

That’s when Anna’s therapist told her about experimental therapy with psychoactive drugs some of his other patients had told him about. He mentioned ketamine therapy, a treatment offered by a colleague of his, Vladislav Matrenitsky. Despite never having used any psychoactive substances before, Anna was intrigued; “If nothing else is helping, maybe it’s time to try something more hardcore,” she thought. So she decided to learn everything she could about ketamine.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Anna had a number of concerns, including toxicity, addiction, and her lack of an official diagnosis — her only diagnosis, “burnout,” she’d given to herself. She imagined ketamine to work similarly to anaesthesia, and that’s what worried her; once, after being anaesthetized during surgery, she’d heard voices and had hallucinations of being lost in a maze. She didn’t want to go through something like that again.

In the wrong hands

Ketamine is used by doctors and veterinarians as an ingredient in surgical anaesthesia. First synthesized in the 1960s, it was used as a pain reliever in the Vietnam War before gaining popularity for its relative lack of side effects other than anaesthesia, which can be accompanied by delirium and psychosis.

Medical sedation requires a dose of 2-3 mg/kg of ketamine — enough to hinder both pain and perception of reality, putting a patient in a trance while inducing either vivid or hazy hallucinations. During surgery, these effects are counteracted by other ingredients, so most patients ultimately don’t have any memory of their “trip” afterward. It’s thanks to these same side effects that ketamine has become a popular party drug, as well as a popular drug for rapists.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

“Vitamin K,” or “ket,” as people sometimes call it, can take the form of white powder, pills, or colorless liquid. It usually causes a surge of euphoria, though not as strong as the kind caused by ecstasy. “Ket” users also describe a feeling of complete relaxation, a wave of bliss.

“I felt a peaceful happiness — as if I were about to die. I wasn’t scared, because I accepted my fate. I knew everything was right, and I felt like I was enough, even in my existential loneliness,” said Karina, a clinical psychologist, about her ketamine trip.

Her partner, Matvey, however, experienced dissociation during his trip. “My body started ‘leaving’ me,” he said. “I was still within its confines, but its borders had weakened. At that moment, there was less of ‘me’ inside of me. I was observing everything from the sidelines. No other substance I’ve tried has made me feel as ‘unalive’ as ketamine.”

Karina and Matvey are certain they followed the correct dosage because neither of them have fallen into a “K-hole” — a state of deep dissociation accompanied by vivid hallucinations. Many people are afraid of experiencing a “K-hole,” because it can bring anxiety and fear; others actually try to fall into one, as for them it’s the most desirable effect of ketamine.

A corkscrew for the subconscious

“A ketamine hole is the uncontrolled release of negative mental content. What I do is a controlled hole. My job is to let a person fall into it, then to walk on the edge,” Vladislav Maternitsky, psychologist and founder of the ketamine therapy center Expio, told Zaborona.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Ketamine therapy is a new means of treating psychological problems. Including the drug in the psychotherapy process allows the patient to access his subconscious, bringing to the surface repressed trauma and conflict in the form of images and sensations.

How far the patient travels into their subconscious depends on how much ketamine they take. Taking a “psycholytic” dose, for example, puts a patient into a trance or a dream state, while a higher dose — psychedelic therapy — causes a strong dissociative effect, giving the patient a more thorough trance experience. If psycholytic therapy is like watching a movie, psychedelic therapy is like actively participating in it.

According to Maternitsky, taking ketamine in an uncontrolled context can lead to a “bad trip,” inducing panic attacks or triggering phobias. Therapists, however, know how to properly guide a person through their trip.

“Let’s say that, while using ketamine, a woman sees the hand of a neighbor who raped her when she was a child. She’ll tell me about it, and I’ll help her replace the shape with symbols. In order to do that, I’ll go into a trance state so I can think of a good substitute to help her safely get through the experience. Every time is improvisation, creation,” said another therapist.

Doctors taking trips

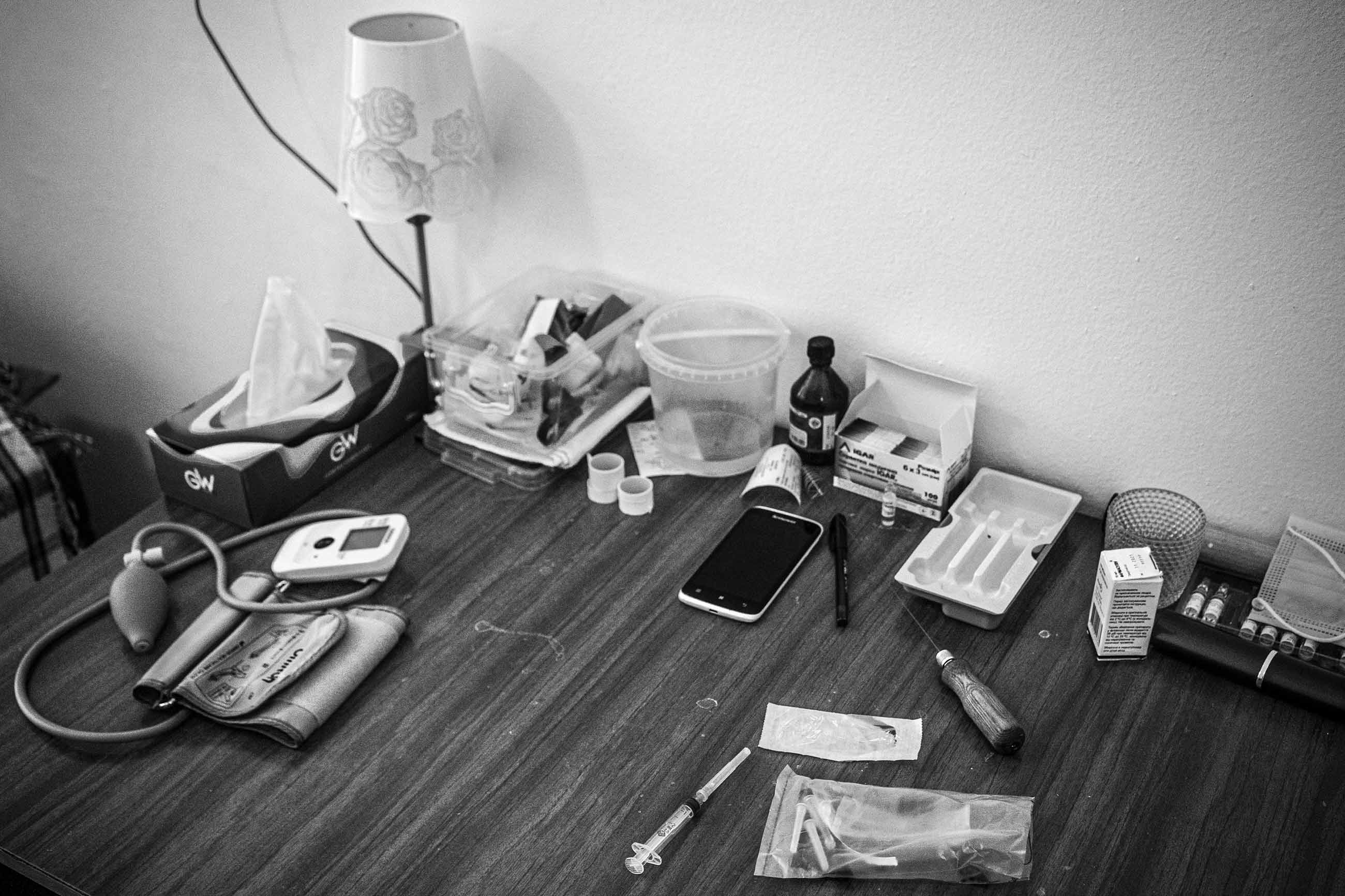

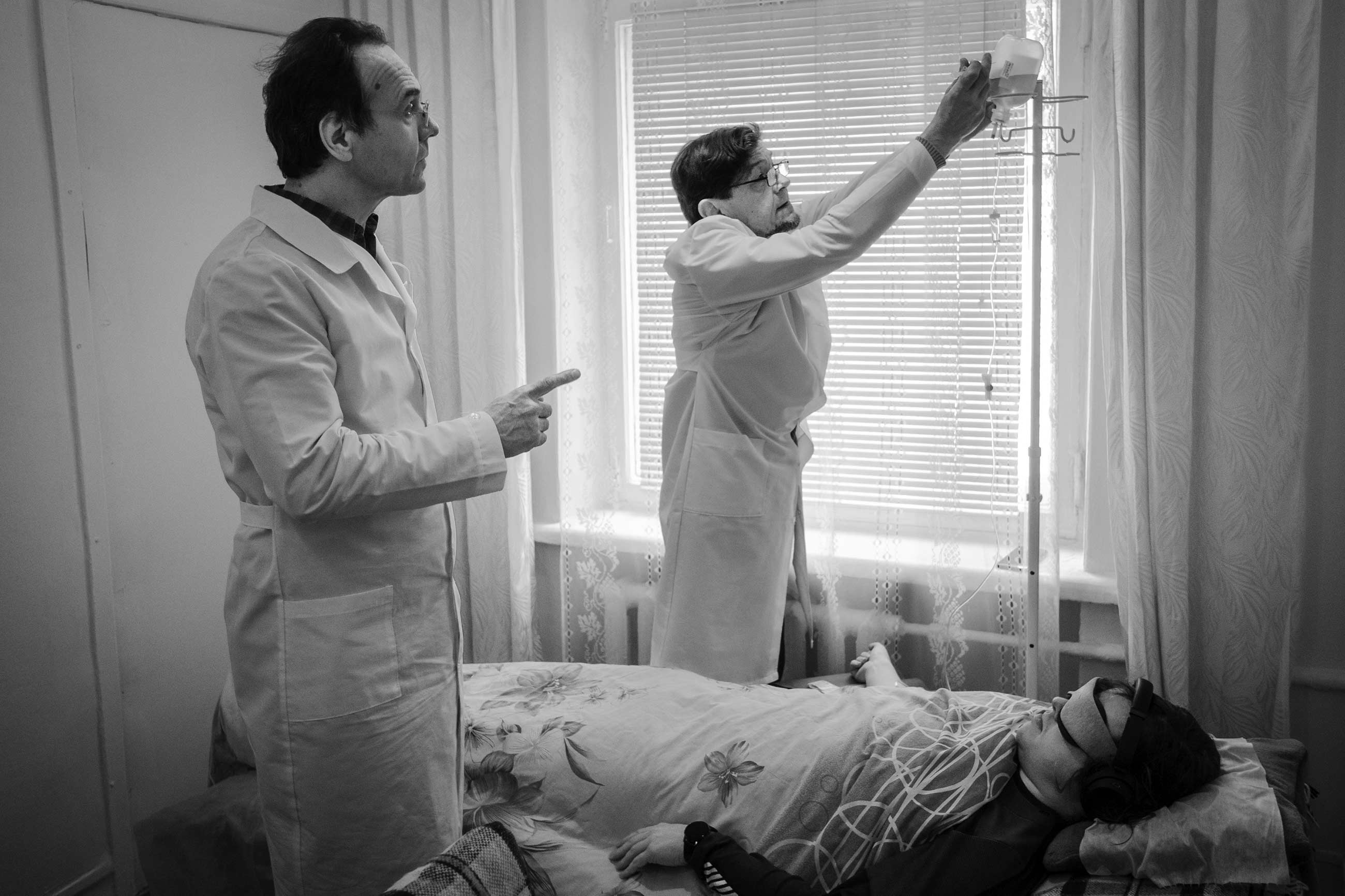

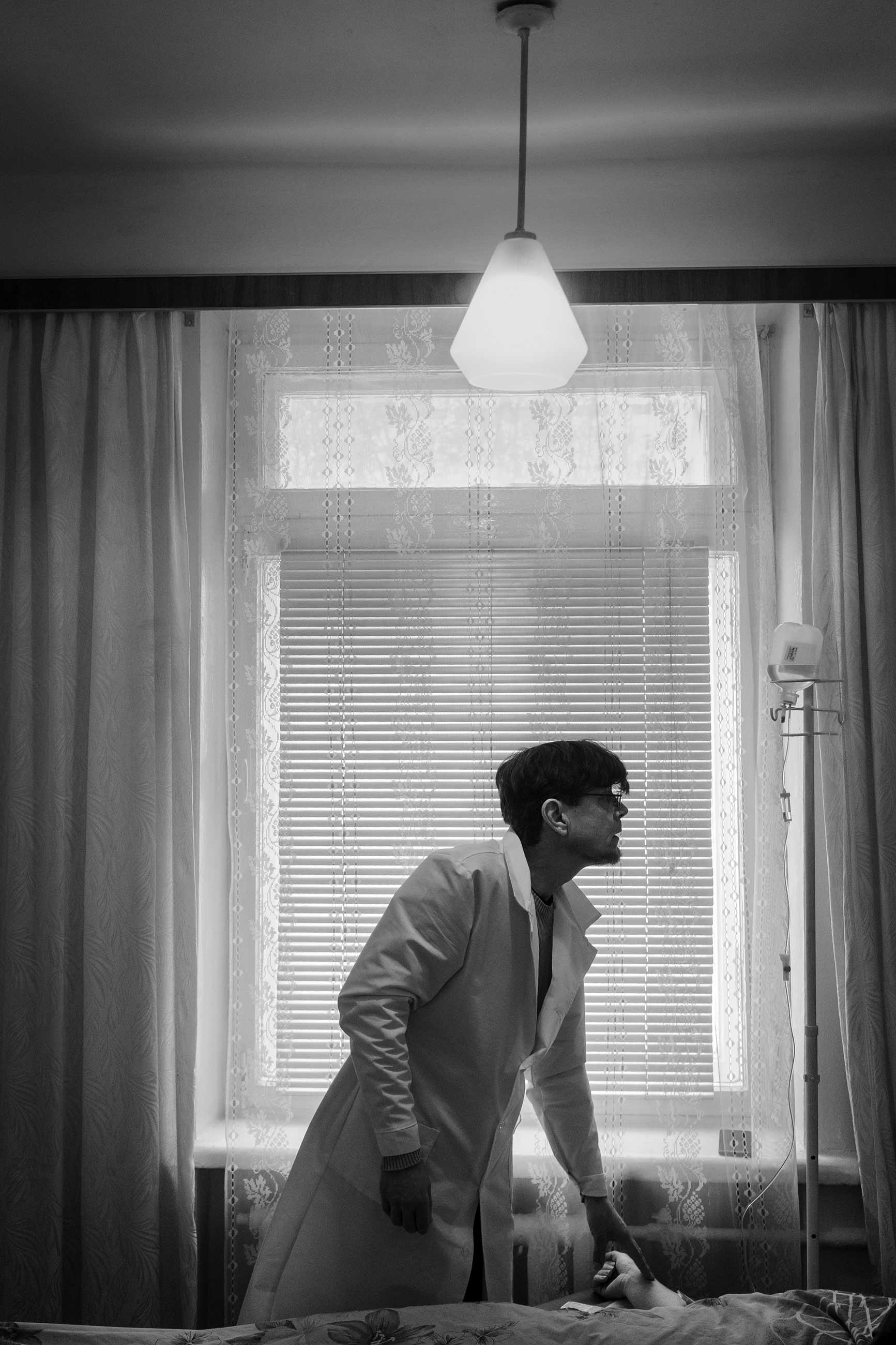

Vladislav Matrenitsky has been a practitioner of ketamine therapy for two years. His clinic, “Expio,” is located in the Gerontology Research Institute in the National Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv. The clinic itself is modest: consisting of a pair of small offices on the first floor of the Research Institute’s clinical building. During the day, it smells like cafeteria food; after 4 p.m., everything becomes quiet, save for the sound of the night guard’s television. In one of the offices, Matrenitsky holds therapy sessions with patients, who he puts in a leather chair covered by a blanket. In the other office, patients sit on a small sofa as they enter their ketamine trance.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

In the center’s short existence, several hundred people have undergone the procedure; only 10 of them, however, approached Matrenitsky about ketamine therapy specifically. “These are generally intelligent people who are looking for something, and they understand why this is necessary for them,” said Matrenitsky.

Before he became a ketamine therapist, Matrenitsky worked in more traditional medicine. In 1986, he graduated from Odessa Medical Institute. He then worked for several years as a district physician in Kyiv while simultaneously defending his dissertation.

But Matrenitsky found that the traditional approach to medicine didn’t provide an answer to his questions; for example, why do some people age faster and get sick more often than others? So he decided to leave his practice to embark on some soul-searching. During this period, he studied alchemy, Buddhism, shamanic healing, and sound therapy; his search took him everywhere from Turkish sheiks to the steppes of Central Asia. Of course, he practiced everything he learned himself.

In Matrenitsky’s telling, he gradually understood that Buddhism is right — all problems come from the mind. He dug deeper into psychotherapy. He enrolled at the P. L. Shupik Ukrainian National Academy of Postgraduate Medical Education and began practicing transpersonal psychology, a branch of spiritual psychology that deals with the altered states of consciousness that people experience in meditations, dreams, during holotropic breathwork, and under the influence of light drugs.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

In his private practice, Matrenitsky saw patients for whom antidepressants hadn’t worked. While psychotherapy sessions usually helped them improve a little, it couldn’t address the roots of their problems. As a result, he decided to meditate with his patients, taking them into trances that allowed them to go beyond their psychological defenses and “rewire” their psyche from the inside. He used transcranial magnetic stimulation, which suppresses the excessive brain activity that occurs during stress. When he discovered that other medical professionals had begun using ketamine to treat drug-resistant depression, he decided to incorporate it into his practice.

Matrenitsky didn’t undergo any special training for his ketamine therapy; he independently studied modern psychotherapy techniques and spiritual practices involving changes in consciousness. To this day, he starts every day with a scientific journal about ketamine use and other methods in order to stay up-to-date with medical innovations.

“And that’s how I learned to use ketamine. I’ve tripped myself. After all, in order to help someone, you have to know how it works from the inside,” said Matrenitsky.

Photo: Invan Chernichkin / Zaborona

A new, fast-acting antidepressant

Back in the 1980s, Soviet scientists began conducting research on the use of ketamine to treat alcoholism and drug addiction. Yevgeny Krupitsky was one of them; by putting patients into ketamine trances, they were able to reach long-term remission in 65% of patients.

“We realized that by using ketamine therapy, we could help patients find new value and meaning in their lives, unconnected to alcohol,” said Krupitsky.

However, in the early 2000s, Russia’s drug laws became stricter, and their research came to an end. Ketamine is currently used in both the U.S. and in Europe to treat drug-resistant depression; the latest research shows that the majority of patients feel a relief in symptoms immediately after using ketamine, and the effects can last, on average, from several hours to several weeks.

In order to prolong ketamine’s antidepressant effects, scientists are testing IV infusions. This could take the form of microdosing four to six injections one to two times a week, or daily if necessary. A study of Canadian psychiatrists who administered ketamine three times a week for two weeks to 37 patients with drug-resistant depression found that 69% of participants stopped having suicidal thoughts after the session ended.

It’s psychedelic drugs’ quick effects that have prompted scientists to study them more actively; drugs like ketamine are also being used to treat other mental disorders. Caroline Rodriguez, a psychiatrist and neurologist from Stanford University, observed that obsessive thoughts decreased in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder who were injected with 0.5 mg/kg of ketamine (a microdose).

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

All of these studies demonstrating the positive effects of ketamine have prompted the U.S. Drug Administration (FDA) to approve the nasal ketamine spray Spravato for the treatment of persistent forms of depression. In a short-term study, Spravato, as well as injections, showed a statistically significant result, which was observed over two days. And in a long-term study in which patients took an antidepressant in addition to Spravato, the symptoms of patients with depression took significantly longer to return than those of participants who received a placebo spray and an antidepressant.

Permission to get high

“I’m not a recreation center; I don’t give ketamine to just anybody. I only provide it to people who actually need it,” said Vladislav Matrenitsky.

Everything begins with diagnosis. If a doctor concludes that a person has serious mental disorders, depression, anxiety, or burnout that needs to be addressed immediately, the person goes to therapy.

Anna rescheduled her appointment with Matrenitsky three times because she was afraid to encounter her fears during the ketamine trip.

“When ‘the day’ was approaching, I started thinking about whether it was worth it. Maybe it’s better just to live in the matrix. At least it’s not as scary. It seemed like it must be an irreversible process that would change my world forever.”

But when she sat down in Matrenitsky’s office, she immediately trusted him. He asked her about the biggest stressors in her life; Anna told him about the anxiety she felt for her son. Out of nowhere, she started crying, even though she didn’t think the topic would trigger anything. That’s when she finally convinced herself to go through with the trip.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

Anna signed a document stating that she knew what she was doing and held responsibility for whatever happened, then she lay down on the couch. Matrenitsky covered her with a blanket, then inserted an IV needle into her left arm. As soon as the first drop of ketamine fell, Matrenitsky told her to focus on the way her body felt. After two minutes, she felt slightly intoxicated, relaxed, and numb in her lips and fingers; her eyes closed under the weight of her eyelids.

Then Matrenitsky asked her to envision the anxiety she wanted to work with. A colorful abstraction floated into her mind, then dissipated like the colors of Holi in India. Some people continue speaking with the therapist when using ketamine, but Anna preferred to withdraw into herself. She did, however, consciously check to make sure she could still move her arms and legs, just in case the doctor tried to do anything to her and she needed to fight back.

“I heard the sounds of the outside world, and they affected the framework in my head. At one point, I saw a green moose coming out of the fog, because someone was playing “Jingle Bells” on their phone. But the more I tried to control the process, the more anxious I became. At some point, I just decided to release myself. It became easier, but it still wasn’t having the experience myself; it was like I was watching it from the side.”

After an hour, Anna came to. The end of her sweatshirt hood was wet with tears. She didn’t know why she had been crying, but from her trance she had felt the tears rolling down her cheek and dropping onto the fabric. She didn’t want the trip to end. “I wasn’t afraid of the feeling. I think this was the therapy’s main effect at a key moment in my struggle with anxiety. I let myself let go; I stopped controlling and started enjoying,” she said.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

For 20 minutes afterward, Anna talked to the doctor about what she had seen and felt, and what it all meant for her. Then her son met her and took her home, where they had dinner. For the first time in her life, Anna let herself relax without feelings of guilt.

Transforming the brain

How ketamine works, and why it’s so effective at mitigating the symptoms of depression — for however short a time — is still poorly understood. One hypothesis is that it blocks NDMA receptors, which are responsible for metabolizing the neurotransmitter glutamate. NDMA is one of the brain’s most important neurotransmitters for regulating the processes of excitation and inhibition in the brain. When a person is chronically stressed, they accumulate a high amount of glutamate, causing them to feel agitated, nervous, and anxious. When ketamine blocks its receptors, glutamate isn’t able to affect a person’s mood so strongly.

Moreover, a study conducted by neuroscientist and psychiatrist Conor Liston in mice confirmed that ketamine first causes changes in brain circuit functioning, improving the behavior of “depressed ” mice for three hours, then stimulates the resumption of synaptic growth. In other words, ketamine facilitates neuroplasticity — the restoration of connections between neurons. On the other hand, mice under stress are quite different from people with depression. “Additionally, there’s no real way to measure synaptic plasticity in humans, so confirming these results in humans will always be difficult,” said neuroscientist Anna Beyeler.

Today, some scientists agree that what’s really important is not the biochemical method by which ketamine operates, but its dissociative effect. According to Carlos Zarato, head of the US National Institutes of Health’s ketamine initiative, the stronger the dissociation a person experiences, the better the therapeutic outcome.

These scientists suspect that psychoactive substances work as “catalysts” of the brain’s subconscious processes, not as drugs. According to Eli Kolp, director of the Ketamine Institute in the United States, the dissociative state is not an undesirable side effect, but a key part of the drug’s efficacy in fighting depression.

Legalizing ketamine

Due to the Ukrainian Ministry of Health’s official acceptance of international treatment protocols, ketamine therapy, like the kind Vladislav Matrenitsky practices, is essentially legal in Ukraine. But according to Oleg Yudin, a medical lawyer, the international protocols introduced are different from clinical protocols.

Oleg Yudin

“Unlike clinical protocols, international protocols weren’t written with the Ukrainian healthcare system in mind. Additionally, they’re not always mandatory. By distancing itself from international guidelines, the Health Ministry puts this onus on the doctor to replace the recommended medicines, equipment or technologies with whatever similar ones are available to him. Doctors are reluctant to take on this kind of responsibility, because if something goes wrong, all the blame will be on them,” Yudin explained.

Not only did Vladislav Matrenitsky decide to start practicing new kind of therapy at his own risk — he also got his own license to use psychotropic drugs. These kinds of permits are issued to specialists and institutions that comply with certain storage requirements. One of the Expio center offices contains a safe of ketamine ampoules, and the room itself is outfitted with an alarm system that Matrenitsky turns on every evening.

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

“It took me half a year to get my license. It wasn’t easy, but now I have access to all kinds of ingredients I want to use in my practice, as ketamine doesn’t help everybody. In a way, I’m a revolutionary. However, like often happens with revolutionaries, they wanted to shut me up. There have been times when ‘purity advocates’ have tried snitching on me, claiming I’m doing things like turning people into zombies,” said Matrenitsky.

In 2019, the Ukrainian State Drug and Medication Control Service received a complaint about Expio illegally providing psychotropic substances. The complaint indicated that the center didn’t have the proper license; luckily, Matrenitsky showed that there had been a mistake, and the situation was resolved. The license had been issued to the doctor, not the center, but on the website Matrenitsky had used an inaccurate wording.

Today, Ekspio, the only clinic of its kind in Eastern Europe, is free of legal problems. As a result, people from all over the world come to Kyiv to get ketamine therapy. According to Matrenitsky, he’s already had an American patient, and he’s currently in touch with a prospective patient from Iran.

Not a panacea

Within a few days of her session, Anna came to some realizations: for one, she realized how much control she had been trying to exert in her relationships with her son, her mother, and even her dog. Before, if one of her loved ones didn’t answer the phone, she would start trying to contact them on every platform possible, assuming the worst had happened.

“After each session, I would feel more calm, attentive, and open to everything. All my life, I haven’t been able to relax. Now, I don’t blame myself every time I sit down in front of the TV — it’s a totally different quality of life. But the anxiety hasn’t gone away entirely. One time, it came over me at night, but I started treating it differently: I thought back to the visions I’d had while on ketamine, and I meditated on them,” said Anna.

In Anna’s view, one ketamine session is not enough to work through all of one’s subconscious issues. Despite feeling exhausted after her first time, she wants to repeat the experience. She’s not worried about the possibility of addiction, but there is research that suggests that that’s a risk. Of course, the only experiments have been done on mice.

According to Karina, a clinical psychologist who’s used ketamine recreationally twice, the drug is definitely capable of causing addiction. “Ket doesn’t have strong withdrawals. And that’s scary, because it means there’s nothing stopping you from using it again.”

Therapist Erika Smith has also written about the chemical dependence people can develop on ketamine: “According to experts, the addiction is psychological. That means people might feel a strong pull to ketamine, but won’t necessarily experience physical withdrawal. But both physical and psychological addiction can be extremely difficult to overcome.”

Photo: Ivan Chernichkin / Zaborona

That’s why, in Vladislav Matrenitsky’s view, a single ketamine session without the help of a therapist is not a solution — it’s a crutch. Full transformation, on the other hand, can require several months of working closely with a therapist.

“This substance isn’t a panacea — it’s one of a number of available tools,” Matrenitsky told Zaborona. “That means patients should try different methods until they understand what works for them and what doesn’t.”

Translated by Sam Breazeale from Respond Crisis Translation