Mariupol, May 6th. Some of the last civilians who hid from the war are being evacuated from the destroyed building of the Azovstal metallurgical plant. Among them is Anastasiya Mykhilova with her four-year-old son Vanya – the family of a soldier who defended the city. On May 18, the man will be taken out of the plant along with other wounded soldiers. Anastasiya will have to undergo interrogation by the FSB of the DNR in a filtration camp. Zaborona journalist Polina Vernyhor interviewed the woman about everything she went through since the start of the full-scale invasion.

“It seemed that they would shoot a little and everything would be fine”

We lived in the Prymorskyi district of Mariupol – ten minutes walk to the sea. I had a complete family: me, my four-year-old son Vanya and my husband. I worked in a pharmacy, my husband was a soldier of the National Guard, and Vanya attended kindergarten – everything was like in every other family.

On the night of February 24, my husband was summoned to the unit on alarm. Vanya and I stayed at home. Around eight o’clock in the morning, my husband called and told me to take all the documents from the house, take the most necessary things for three days and move to my grandmother. Grandmother lived on Kirova Street, which is closer to the city center.

We arrived there. At that time, other relatives with children were already there. There were eight of us living in a two-room apartment. I left Vanya with my grandmother and went to work. Around 11 o’clock, the walls of the pharmacy began to shake – the city was being shelled from the sky. I was scared. I closed the pharmacy and rushed to my son. Since then, I have not gone to work.

When it all started, I first tried to come up with a game for Vanya – I told him that green-headed monsters were shooting. He once watched a cartoon about such monsters, so when Russian soldiers with machine guns started running near our windows, I said that these were the same monsters from the cartoon. At first, he couldn’t understand: if monsters are bad, then why does dad walk around in a similar uniform? I explained to him that some soldiers are bad and some are good. And dad’s soldiers are good.

I did not see my husband for a week, if not more. He called us once – tried to calm us down, and said that everything will be fine. It seemed to us then that they would shoot a little and everything would be fine. We thought that we would return home at the beginning of March at the latest. That’s why we didn’t even talk about evacuation.

But every day the shelling got stronger. We hid from it mostly in the toilet or bathroom. When the shell hit something nearby, we ran out into the vestibule between the apartments. Adults were on duty at night – someone was always awake. When the shelling started at night, we jumped up and ran to hide. We lined up our shoes to immediately grab them, throw them out into the hallway, or put them on and run. We didn’t take off our clothes either: we slept dressed. When it was already cold and there were not enough blankets, we covered ourselves with down jackets. I remember that my grandmother had a fur coat – we slept under it.

At the beginning of March, everything was turned off completely: water, gas, electricity, heating. We started cooking outside. We kindled a fire near the entrance and cooked mostly boiled potatoes, and eggs – something that does not spoil because the refrigerator did not work. Sometimes we cooked soup, but in general, we tried to save water.

Our men – my uncle and his father-in-law – went to the well to draw water. We tried not to give it to the children – they drank the remains of bottled water. Three children lived with us: my Vanya, my seven-year-old sister, and my 15-year-old cousin.

Every day the food supply decreased – we began to save. It was scary that the children would not have enough food, so we tried to postpone, divide, and eat less.

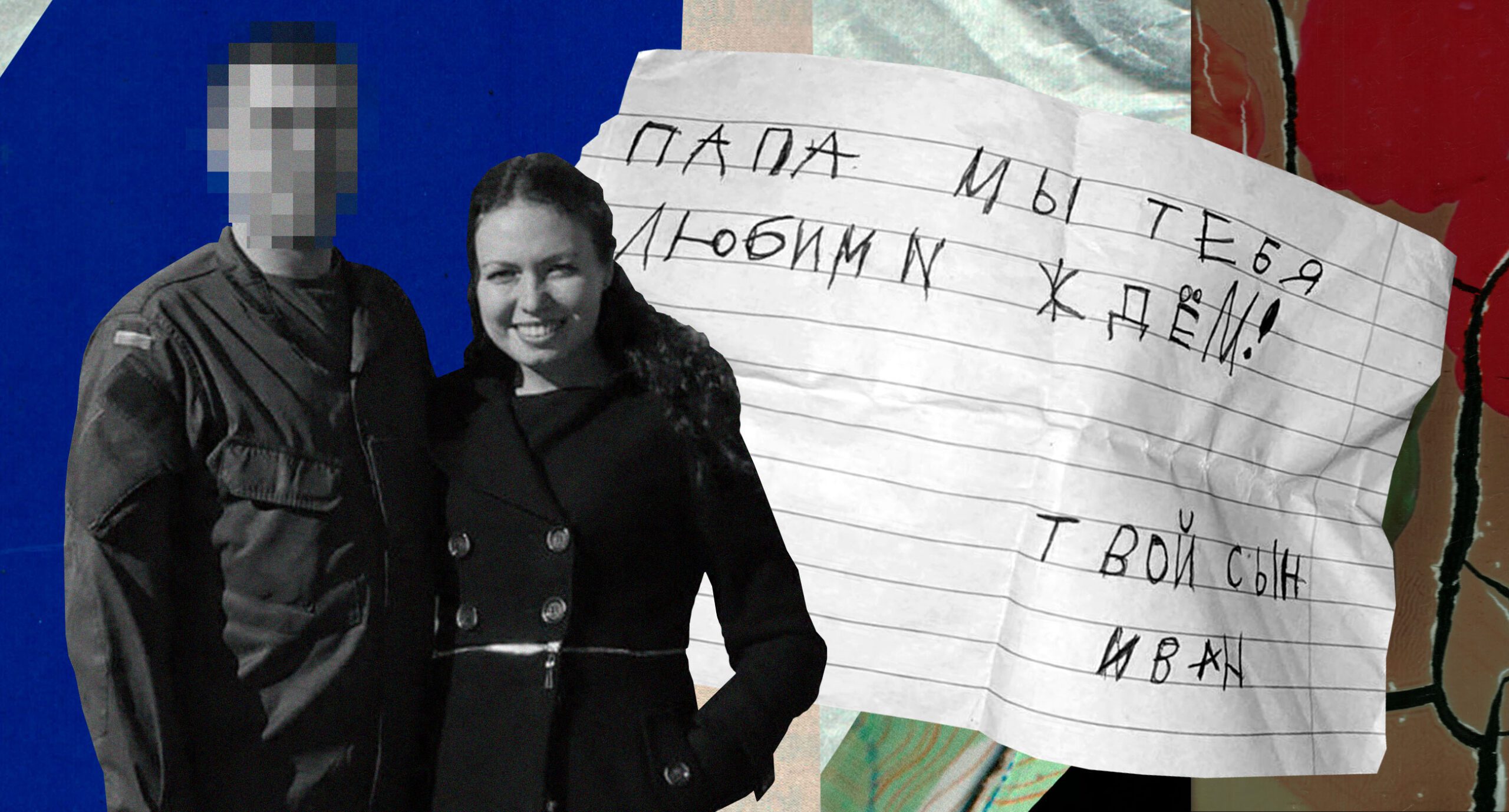

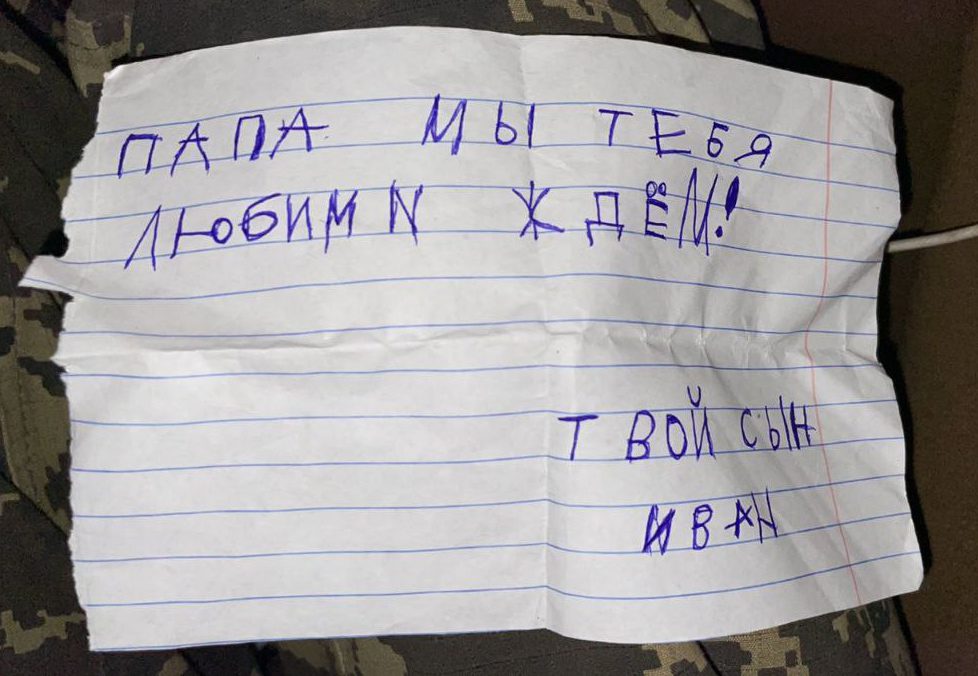

Photo courtesy of Anastasiya Mykhilova

Azovstal

On March 9, my husband came. He said that if he did not evacuate us from here, we would die. He came for us the next day. He took us out in two groups: first women and children, then men.

We arrived at the bunker at Azovstal. There were already beds ready for us – wooden pallets stacked together, and sweatshirts, pants, jackets on top. If you put it all together, it was a pillow, if you cover yourself with it – a blanket, well, we used it as a mattress too. There were children, adults, and dogs in the bunker — a total of 42 people, eight of whom were children. Vanya was the youngest, and most of them were 10-12 years old.

The room looked like a long corridor. It was located two floors deep. The corridor was ten meters long, and there were couches along it. Each family slept on one couch: four, five people. We had a ventilation room. We set up a table there, played cards, dominoes, and children drew, we invented various games for them.

There was a room where water was stored. The bunker was prepared in case of war even before February 24, so there was a good supply of mineral water. There was a separate room with food – it was locked with a key. There was also a toilet room – there were buckets. They were taken out one by one.

In the bunker, we felt very well when rockets fell around Azovstal. It feels like you’re swimming in waves — the whole building was moving from side to side.

Photo courtesy of Anastasiya Mykhilova

Photo courtesy of Anastasiya Mykhilova

One candy for eight children

A family lived with us – husband Vova and his wife Natalya. They were responsible for food: they went upstairs outside, kindled a fire, and cooked. The soup was cooked once a day — it was a large 9-liter pot, into which some cereal and a can of stew were thrown.

Food was found on the street, in local bombed-out stores. Whoever could put on a factory helmet, went out into the street and simply ran to a store or some kind of warehouse, or to destroyed abandoned buildings. Sugar, tea bags were brought. It was for all of us.

If there were candies or something sweet, they were given only to children. It got to the point that one candy was cut into pieces so that everyone had his piece. I remember that they once found two apples, a little shriveled, but normal. We cut them into pieces and distributed them to all the children. We had contests among the children for the best drawing – even with gifts in the form of galette cookies. It was a holiday for them.

My husband tried to come once every three days. He brought flour, canned goods, and cookies. We used this flour to make cakes, pancakes for children, donuts. Husband tied bags of food to his bulletproof vest and ran like that. To get from his bunker to ours, he had to run for probably an hour. He checked whether everything was fine with us, and told some news because there was no connection.

“Star”

On April 6, the husband came and said: “I have to go, I will come for you tomorrow” – but he never came. For a long time, we did not know anything: we counted the hours, the days until we heard anything about him. Then a soldier came and said that a military hospital would be built on the site of our bunker: there was not enough space for wounded soldiers. He said that we will be moved to another bunker. At night, when the shelling was less intense, the soldiers helped us move things. We ran to the touch because absolutely nothing was visible.

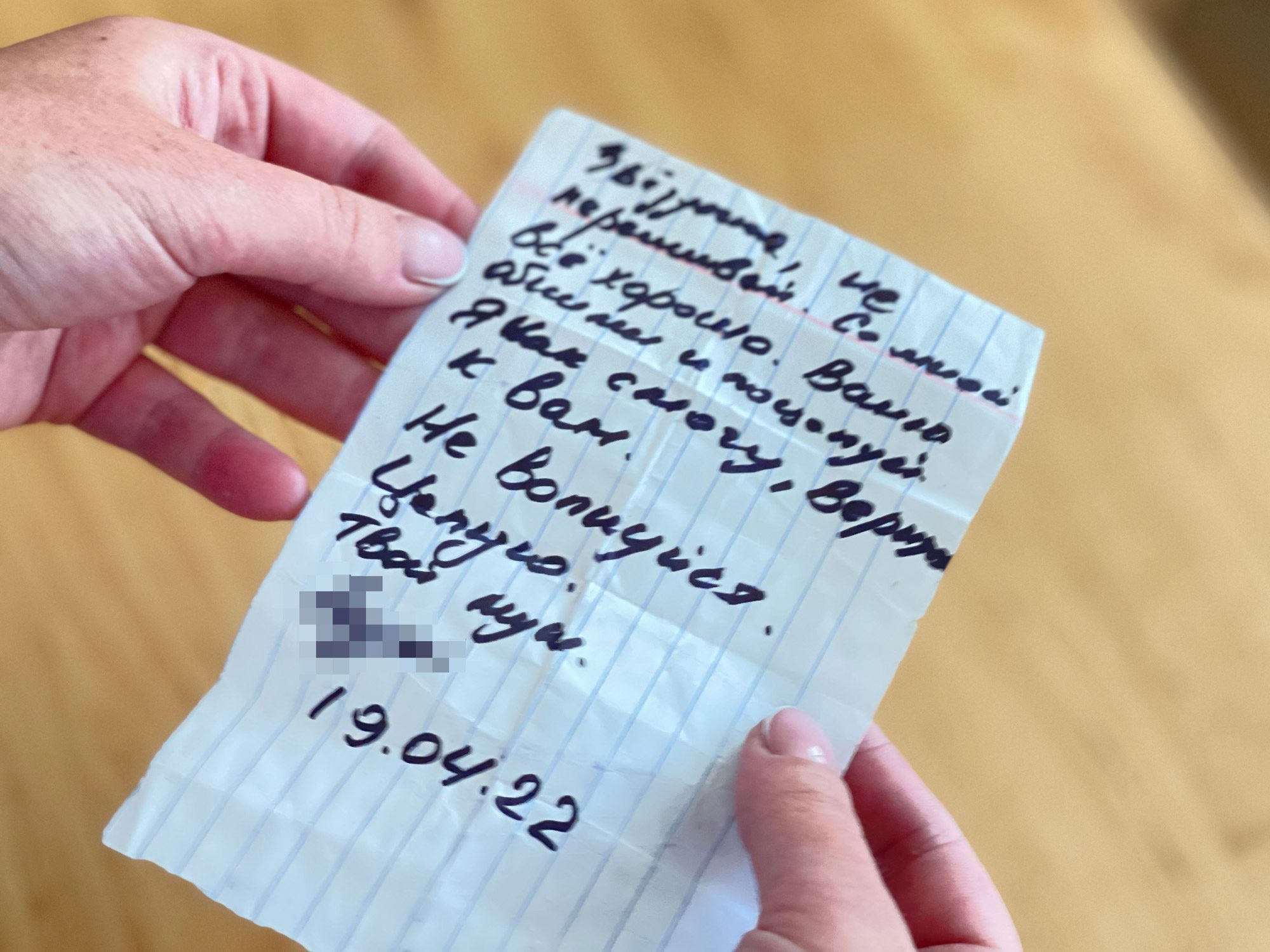

I recognized one of the soldiers who helped us. He was from the unit where my husband served. I approached him, asked where my husband was, what happened to him, and why he did not come. He promised that he would find out and offered to write a note. In three days he brought a note in response. He said that my husband is in the hospital, he has two wounds – in the thigh and shoulder, but everything is fine. The note, dated April 19, began with the word “Star” – it was like a code word. If this word hadn’t been there, I might not have believed it – I would have thought that I was just being reassured and someone else had written the note. My mother calls me a star since I was little. He knew about it and also called me so. He wrote that everything is fine with him and that he will return to us as soon as he can.

Afterward, my husband sent his greetings to us through his commander. He came and said: everything is fine with him, he is recovering. Once the commander came with a garbage bag. He said: it’s from your husband. I opened it – and there was a piece of cheese: he gave it to us from the hospital.

Photo: Vitaliy Shmakov / Zaborona

Evacuation

In the new bunker, everything seemed to be the same as in the previous one. There was a lot of talk about evacuation. We kept hearing about the green corridors, but several times they failed because the Russians opened fire on them. It happened that we were already going out, but the shelling started and we ran back. This lasted for a week until the Red Cross took over the evacuation.

We could be ordered to leave at any moment. Many things could not be taken, because everything at the plant was destroyed, and it was necessary to pass very quickly, squat, and step over.

On May 6, the Ukrainian military came to us and ordered us to leave. We were the last of the civilians who were taken out of Azovstal. First, 10 people of retirement age and those with chronic diseases came out. The next 10 people were us families with children. And then those without children.

We were led out by three soldiers. There was a moment when a quadcopter started flying above us. We hid. Then waited until it flew by and left. At the entrance of the factory, they said that we will be filtered, and I don’t have to tell that my husband is a military man.

I understood that it would be like this long before that, so I told Vanya that dad had gone to work at sea. Even now, if you ask him, he can say: “my dad is at sea, fishing.”

“And why do you have such clean hair, as if you were not sitting in a bunker?”

We left the plant, were met by volunteers of the Red Cross, and were taken to Bezymenny [a village in the Donetsk region, on the coast of the Sea of Azov] for this filtration. There they searched all our things, took fingerprints, made us undress, and looked at our collarbones, hands, palms – probably looking for tattoos or characteristic calluses from carrying weapons. It was unpleasant. I didn’t have any photos of the husband or his phone numbers on my phone. Then we were led to a tent where we had to write explanatory notes.

There was a chair in the tent, six soldiers were sitting opposite it. One of them was not wearing a military uniform. Then I found out that it was an employee of the “FSB of the DNR” who was looking for information about us. It was necessary to describe in detail how I got to the factory, and who brought me there. My family and I made up a story that we came to the factory with our neighbors.

When I was writing an explanation, another soldier entered the tent. He came up and started showing pictures of my husband on his phone, where he stands in uniform with other soldiers. I did not have this photo. I still don’t know where it came from. He asked if it was not my husband by any chance. I said no. I clearly stuck to the story that my husband is at sea, on a flight, and I don’t know where he is now. Then he swiped the photo — and in the next photo, my husband was holding Vanya, sitting in our living room on the sofa, in ordinary clothes. The soldier asked if it wasn’t him too. Then I had to say.

Later, people from these tents began to be transferred to other tents where they could sleep – there were folding beds with pillows and blankets. For us then, after the bunker, these conditions were ideal: there was also a stove, and it was warm. The bunker was very cold.

They took my family to living tents. And they did not take me and my child. We sat under the tent with the soldiers from morning till night. I asked the military why they were not taking me to living tents. They answered that they have additional questions for me. Then I got scared. I asked to take Vanya to his grandmother. I got the birth certificate and told grandmother: if something happens, she should give Vanya to my mother so that he is not left here.

At six o’clock in the evening, I was taken to another tent, where interrogations take place. They asked for personal data, who I knew from the military unit, where, at which points my husband could stand, what he was doing. Somehow they already knew what unit he was from. They named his position, his rank. I gave them fictional names then. I had to say something because they said: “If you don’t give full information – at least some useful information – you will stay here and we will not let you go.”

They knocked on the table, shouted, insulted me, and cursed. They stood and discussed me, touched my hair, said: “Why is your hair so clean as if you were not sitting in a bunker.” I heard it all, it was unpleasant.

They asked how I feel about the president, how I feel about the fact that there are Nazis in Ukraine. I cried there and asked to be left alone because I don’t know anything. In parallel with my questioning, more evacuees were brought. Someone was quickly questioned, and someone was interrogated. All were searched. Those who had knives were taken away. However, the money was not taken from us. The people who led us out of the bunker warned us to hide gold and money. I sewed valuables into the hood of the jacket just in case.

I was asked what I was going to do next. I said that I would go to Zaporizhzhia. The Russian military said: “Why do you want to go to Ukraine? You will be better off in Donetsk, life is good there. We will help you leave. What did you forget in this Zaporizhzhia? We will do the same with Zaporizhzhia as with Mariupol. There’s nothing to do there, it’s better to go to Donetsk.” They told me that if my husband surrenders voluntarily, I will see him in half a year. Like, this is the best option for me. They said that he framed me. They spoke abomination about him. They said that I was here because of him, that they would find him.

My phone was taken away. They tried to call the husband via Viber, but at that moment he had already lost it. So after midnight they finally let me go to a living tent. All night I thought that they would not let me go. It was scary. In the morning I went to the Red Cross and told how it all happened. The volunteer said that he was taking care of me, that I should not worry, and that they had no right to keep me here.

We were there for perhaps two days. The children at least saw the sun, because we spent two months in the bunker without going out. Our tent was put on constant watch. Nowhere else they were on duty – only near our tent. And night and day, military men with weapons stood nearby.

“Why isn’t dad here?”

On May 8, Red Cross and UN volunteers put us on buses and took us to Zaporizhzhia. When we were driving through the territory controlled by Ukraine, we were able to call relatives. It turned out that messages were written to them on my behalf. They asked where my husband might be.

Photo courtesy of Anastasiya Mykhilova

When we got to Zaporizhzhia, we couldn’t believe that everything was almost over, that we were already safe. The most pleasant thing was the field all around. We cried on the bus because it’s just a field, a street, nature.

From Zaporizhzhia, we were first taken to Yaremche [in the Ivano-Frankivsk region], and then volunteers helped us rent housing in Kyiv. Here I took Vanya to a psychologist. She said that he has no abnormalities. But he constantly mentions the war.

When we left Zaporizhzhia, I offered my son to go get ice cream. And he asks: “Mom, is the war over? Why aren’t they shooting?”. I said it was over. And he immediately had a question: “Why isn’t dad here? The war is over, why isn’t he with us?” I tell him then: “Dad is not there, because for him the war is not over yet.”

He watches videos on the Internet of parents returning home and children running to them. Recently, he asked why everyone’s parents come back, but not his dad. I can’t explain it to him, because I don’t know how.

“I want to have a complete family, I don’t need anything else”

On April 19 I got the last news from him. He does not get in touch. We were confirmed by the National Guard hotline that he is now in Olenivka [a penal colony in the Donetsk region not controlled by Kyiv]. He is alive and more or less healthy, recovering from injuries. I know that some of the prisoners called from there. He didn’t call.

On May 18, he was evacuated from Azovstal along with other wounded servicemen. A video of this evacuation was posted online. I saw him on it. From that moment I started calling and asking where he was. I was told that he is not on the list of evacuees. I explained that everything is fine with my head: I can see him. At first, he was considered missing.

On May 24, I received a phone call from the headquarters of Deputy Prime Minister Iryna Vereshchuk. They said that he was found. Since then, he has been listed as a prisoner of war and is in line for exchange. We called the SBU, left an application there, and attached a photo. Honestly, I can’t even remember everyone I called.

We teamed up with other relatives of the defenders of Mariupol. Everyone has one big problem now, so we are like a big family – we try to tell each other something new. We are ready for anything, but we don’t know where else to turn. We called everywhere and wrote everywhere. I understand that it will be a long process, not everything is so easy. I want to help, but I don’t know how. They are not communicating with us now. We call all possible numbers, and they tell us to wait. And that’s all.

I really want Mariupol to be freed from the occupiers. I was born in Mariupol, my child was born there, I met my husband there. Everything good was in Mariupol. But I probably won’t be able to return yet. It’s hard to watch what’s happening to my city, but I watch anyway. Those places where it was pleasant to live are now gone – they are all broken.

Photo: Vitaliy Shmakov / Zaborona

I dream that our family will become complete again, that Vanya’s father will return and we will live together. And we don’t need anything else. I don’t regret anything – I don’t even regret that so many things were left at home.

I am terribly afraid that I will have to run away again, hide somewhere. Since I came to Kyiv, I am constantly afraid that everything will happen again. For some reason, I want to believe that the city is protected here, that it will definitely not be abandoned, as it happened with Mariupol.